Africanising generative AI

How can Africa benefit from artificial intelligence

By Rafiq Raji

Introduction

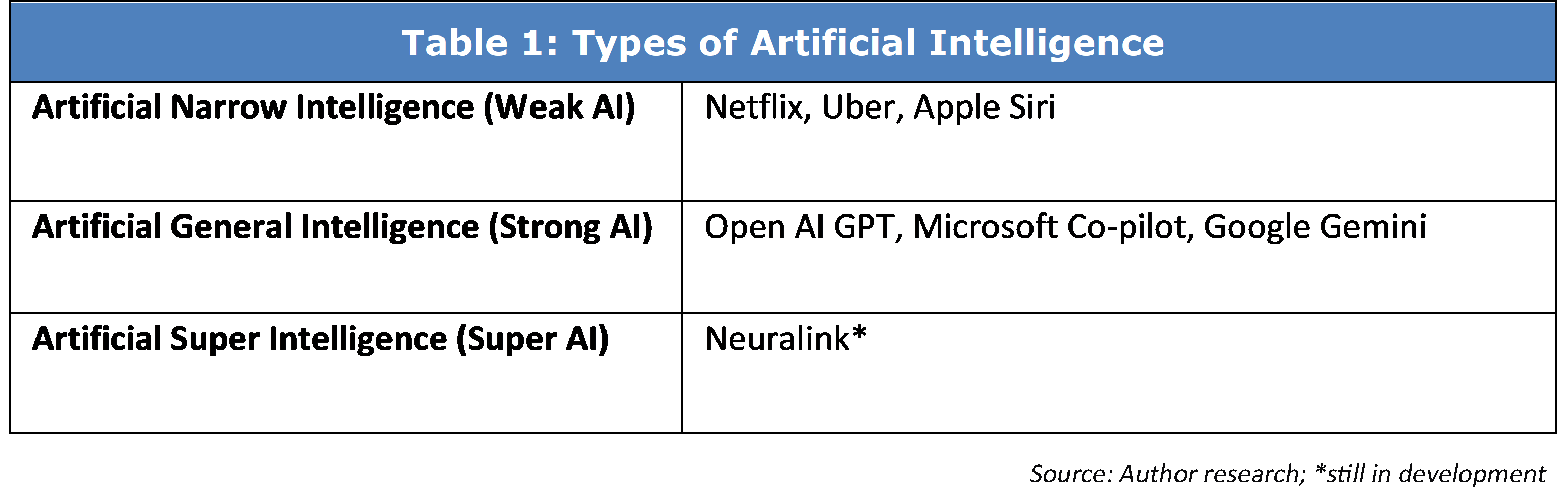

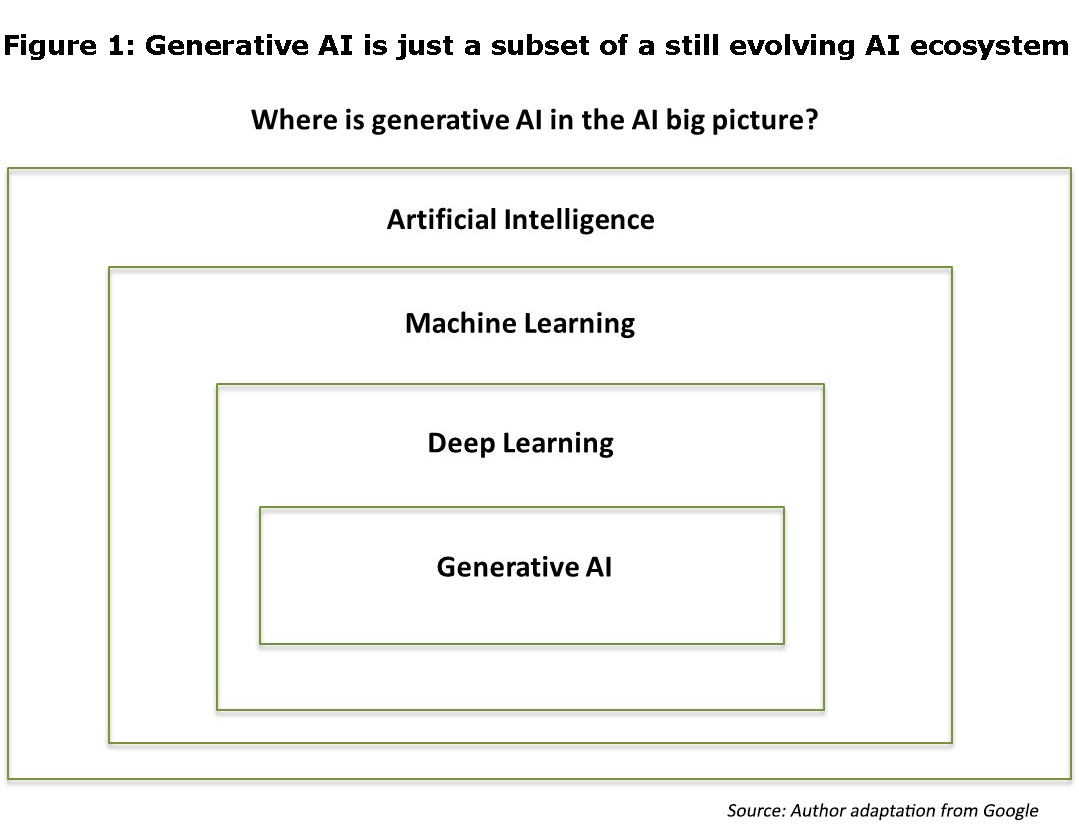

Artificial intelligence (AI) is “the ability of computers to imitate cognitive human functions”. AI that “create[s] new content, like text, images, music, audio, and videos” is generative AI, as it uses a “machine learning model to learn the patterns and relationships in a dataset of human-created content, [after which it] uses the learned patterns to generate new content.”[1] Generative AI, which is a form of artificial general intelligence (or strong AI), is a next step from artificial narrow intelligence (or weak AI), which many already use in myriad utility and entertainment apps and virtual assistants, ranging from Netflix, a video streaming service, Uber, a ride-hailing service, to Apple’s Siri, a digital assistant (see Table 1 and Figure 1).

Generative AI has recently gained prominence because of advances made by Open AI’s GPT, a chatbot application, which relies on large language models (LLM) that are trained with humongous data to provide answers to users’ questions on its own without predetermination. Tech giants, Microsoft and Google, for example, have since quickly developed competing chatbot applications, but to mixed reviews. Such is the case now that firms, governments, and society in general, have generative AI as one of their topmost technological priority.

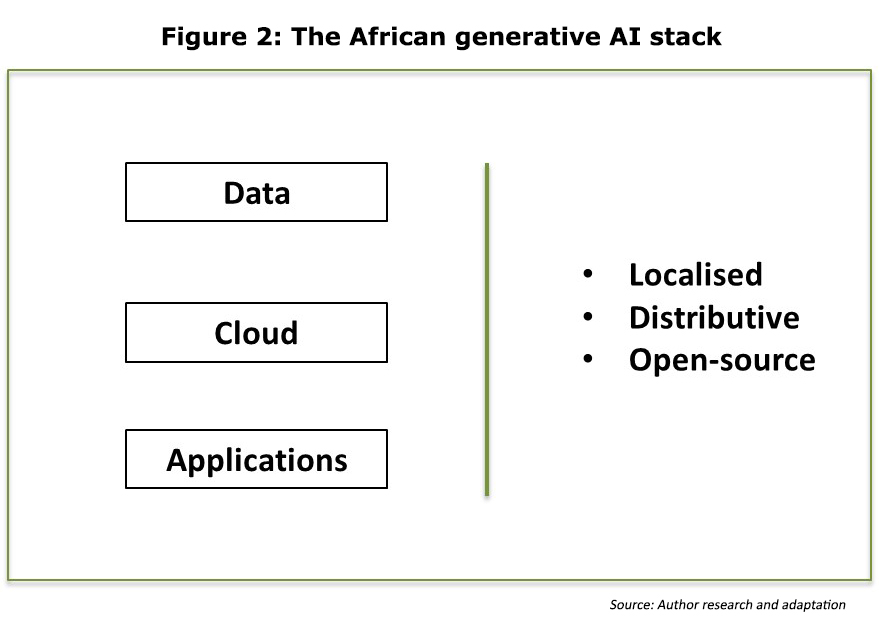

Where is Africa in all these? We find there are gaps, challenges, and opportunities for African participation in generative AI. When globalised, centralised and closed-source, as most of generative AI currently is, legacy infrastructural constraints stand in the way of African participation. But as generative AI is already evolving towards localised, distributive and open-source applications, we make the case that there will be increasingly more room for those otherwise exclusionary and globally centralised generative AI scale barriers to be overcome by African stakeholders.

Current African generative AI gap is an opportunity

Current African generative AI gap is an opportunity

Generative AI is already becoming agile, as smaller language models are already being tested to save cost.[2] Otherwise wholly cloud-based operations are evolving towards a distributed model between a back-end cloud and increasingly powerful computer chips powering a front-end interface and adaptable database on smartphones.[3] That is, some generative AI queries will increasingly be processed locally on smartphones without the need to refer to a distant cloud. Even so, generative AI will remain largely centralised, as the cloud, which is already dominated by just a few global tech firms, will be required to power expectedly more tasking queries at mass. Africa’s infrastructural deficits – Africa has less than 1% of global cloud capacity, for instance[4] – will compound this dependence for its firms, governments and consumers. While there is probably little that African stakeholders can do quickly enough at this time about the global infrastructural centralisation of generative AI around the cloud, there is much that the continent can still do about ownership of the data that will feed and train the models, as well as the cloud repositories for these datasets.

Right now most of the training data for existing AI models comes from Global North and is not very representative of African social and cultural realities. Without an enforcement mechanism of its own to ensure that African training data is appropriately priced and applied, the continent is already disadvantaged at the outset of what is becoming a fast-paced generative AI revolution. Some global media content creators are adopting a litigious approach to enforce their copyrights.[5] This is probably not an option open to most African content creators, as much of what is supposedly African content is not necessarily African-owned, nor African-domiciled, and the potential returns will often not be significant enough to warrant the likely higher costs of litigation. Still, there is clearly a need for an “Africanised” generative AI, one that applies the accurate cultural context to African data and its consumers.[6],[7] African languages must be more represented in large language models (LLMs). This is key for opening up AI for wide scale use in sectors like agriculture. Right now there are around 250 million small-holder farmers across Africa who produce 75% of the food for the continent. If GenAI can support natural language interaction in multiple African languages, services could be provided at a greater scale and across borders and cultures. African culture and context are also massively underrepresented in AI training data, and as a result will perform worse in African workplaces. The way Africa is currently being portrayed comes primarily from Western sources – media, development agencies or foreign universities. By using representative data sets created and curated by Africans, we can create equitable data ecosystems, and incorporate indigenous knowledge that reflect current realities on the continent. Besides, African legislatures could take a cue from their counterparts in America and elsewhere in the developed world, by legislating that African data used for training generative AI models should be paid for as well.[8]

Right now most of the training data for existing AI models comes from Global North and is not very representative of African social and cultural realities. Without an enforcement mechanism of its own to ensure that African training data is appropriately priced and applied, the continent is already disadvantaged at the outset of what is becoming a fast-paced generative AI revolution. Some global media content creators are adopting a litigious approach to enforce their copyrights.[5] This is probably not an option open to most African content creators, as much of what is supposedly African content is not necessarily African-owned, nor African-domiciled, and the potential returns will often not be significant enough to warrant the likely higher costs of litigation. Still, there is clearly a need for an “Africanised” generative AI, one that applies the accurate cultural context to African data and its consumers.[6],[7] African languages must be more represented in large language models (LLMs). This is key for opening up AI for wide scale use in sectors like agriculture. Right now there are around 250 million small-holder farmers across Africa who produce 75% of the food for the continent. If GenAI can support natural language interaction in multiple African languages, services could be provided at a greater scale and across borders and cultures. African culture and context are also massively underrepresented in AI training data, and as a result will perform worse in African workplaces. The way Africa is currently being portrayed comes primarily from Western sources – media, development agencies or foreign universities. By using representative data sets created and curated by Africans, we can create equitable data ecosystems, and incorporate indigenous knowledge that reflect current realities on the continent. Besides, African legislatures could take a cue from their counterparts in America and elsewhere in the developed world, by legislating that African data used for training generative AI models should be paid for as well.[8]

Global tech firms have already started making generative AI services available to African consumers regardless. But these remain largely generalised products devoid of the proper African context.[10] To be clear, these generative AI products already have African training data. But faux pas like black Nazis and African popes from Gemini, Google’s generative AI product, point to difficulties these models still face in interpreting their African training data accurately.[11],[12] The mishaps stem from a dominance of images and text relating to white people in current generative AI models, with the relatively minuscule data on non-white people being creatively programmed to project a shallow egalitarianism to predictably ill effect.[13] There is certainly a need for generative AI models to have training data in African languages if it is to be useful for the majority of the continent’s still largely agrarian populations.[14], [15] But there is currently a dearth of African training data for generative AI models, which is a gap and an opportunity.[16],[17] This is not necessarily a herculean task, as the Singaporean case shows, whereby a generative AI chat application that better reflects Southeast Asian languages has already been built.[18] In fact, African governments, Nigeria, for instance, are beginning to make similar efforts to enable the inclusion and availability of training data in African languages.[19] India’s “societal AI” approach, whereby generative AI is used to fill hitherto difficult text-related local digital inclusion adoption gaps with voice and video interface tools, is also an almost exact analogue for the African case.[20]

Global tech firms have already started making generative AI services available to African consumers regardless. But these remain largely generalised products devoid of the proper African context.[10] To be clear, these generative AI products already have African training data. But faux pas like black Nazis and African popes from Gemini, Google’s generative AI product, point to difficulties these models still face in interpreting their African training data accurately.[11],[12] The mishaps stem from a dominance of images and text relating to white people in current generative AI models, with the relatively minuscule data on non-white people being creatively programmed to project a shallow egalitarianism to predictably ill effect.[13] There is certainly a need for generative AI models to have training data in African languages if it is to be useful for the majority of the continent’s still largely agrarian populations.[14], [15] But there is currently a dearth of African training data for generative AI models, which is a gap and an opportunity.[16],[17] This is not necessarily a herculean task, as the Singaporean case shows, whereby a generative AI chat application that better reflects Southeast Asian languages has already been built.[18] In fact, African governments, Nigeria, for instance, are beginning to make similar efforts to enable the inclusion and availability of training data in African languages.[19] India’s “societal AI” approach, whereby generative AI is used to fill hitherto difficult text-related local digital inclusion adoption gaps with voice and video interface tools, is also an almost exact analogue for the African case.[20]

Generative AI will compound existing African developmental constraints

Bias, copyright, job redundancies, misinformation risk, high costs, and dystopian fears are some of the top-of-mind questions about generative AI at the moment, and how they are addressed will determine how much the technology succeeds.[21] And while global, these issues are at the very heart of the African technological and developmental dilemma. Much of the bias observed with generative AI thus far make writ large the inherent disadvantage of Africa’s low content and infrastructural inputs into global AI. African businesses and governments can certainly not afford the huge investments and outlays required to train and deploy large language generative AI models, as the continent does not as yet have enough data centres, cheap and surplus electricity and scale economies required to do so optimally. Offshoring, a budding African tech opportunity, will almost suffer from AI-induced job redundancies, as what companies would otherwise contract out will increasingly be possible to do in-house cost-effectively with generative AI.[22],[23]

Incidentally, some of the dystopian fears about generative AI are already becoming an African reality, as loss of agency, misrepresentation of expertise, politically sponsored AI-backed misinformation and mischief are beginning to become widespread. The risk of generative AI racial stereotyping is not only significant, but will take deliberate effort to control, as a multifaceted global analysis of thousands of AI images in 2023 by Rest of World, a widely read tech publication, shows.[24] Termed generalization, generative AI models are able to, and do in fact, do things they are not trained to do.[25] Thus, there is still a lot that AI experts cannot control or explain about the outputs of generative AI models, as no one can say for sure what the output of any generative AI model would be, nor can anyone be confident as yet that guardrails to forestall mishaps will be effective.

The fast pace at which AI is evolving will make it difficult to regulate effectively over the short to medium term, although this should not discourage well-meaning efforts to do so.[26] Global initiatives are already afoot to regulate AI.[27] After much ado since April 2021, the European Parliament finally passed its Artificial Intelligence Act in March 2024, for instance.[28], [29] Some regulatory suggestions, like installing AI limitations into hardware and algorithms, however, will be outrightly discriminatory, especially for Africans, whose currently compounding disadvantages, ranging from paywalls to out-of-reach expensive smartphones, will be further entrenched.[30] In fact, it will simply balkanize AI for Africans at the outset, thus engendering further exclusion of African countries. Clearly, African governments and stakeholders need to start asserting themselves and ensuring they are being heard in the rapidly-evolving global AI governance landscape.[31],[32],[33],[34] Even so, hardware gentrification is almost inevitable regardless, as high-end AI-enabled smartphones are increasingly out of the reach of the average poor African. Also, as generative AI requires significant computing resources, African firms will be forced to entrench their reliance on cloud services by the few dominant global tech companies, to either store their data, manage the generative AI applications they have procured for their businesses, or to develop their own generative AI applications reliably.[35] This does not in anyway discountenance the exigency for more African data centres; for at the very least, the provenance of African data should be African, in data centres located on the continent, which could either be locally-owned or foreign-owned.

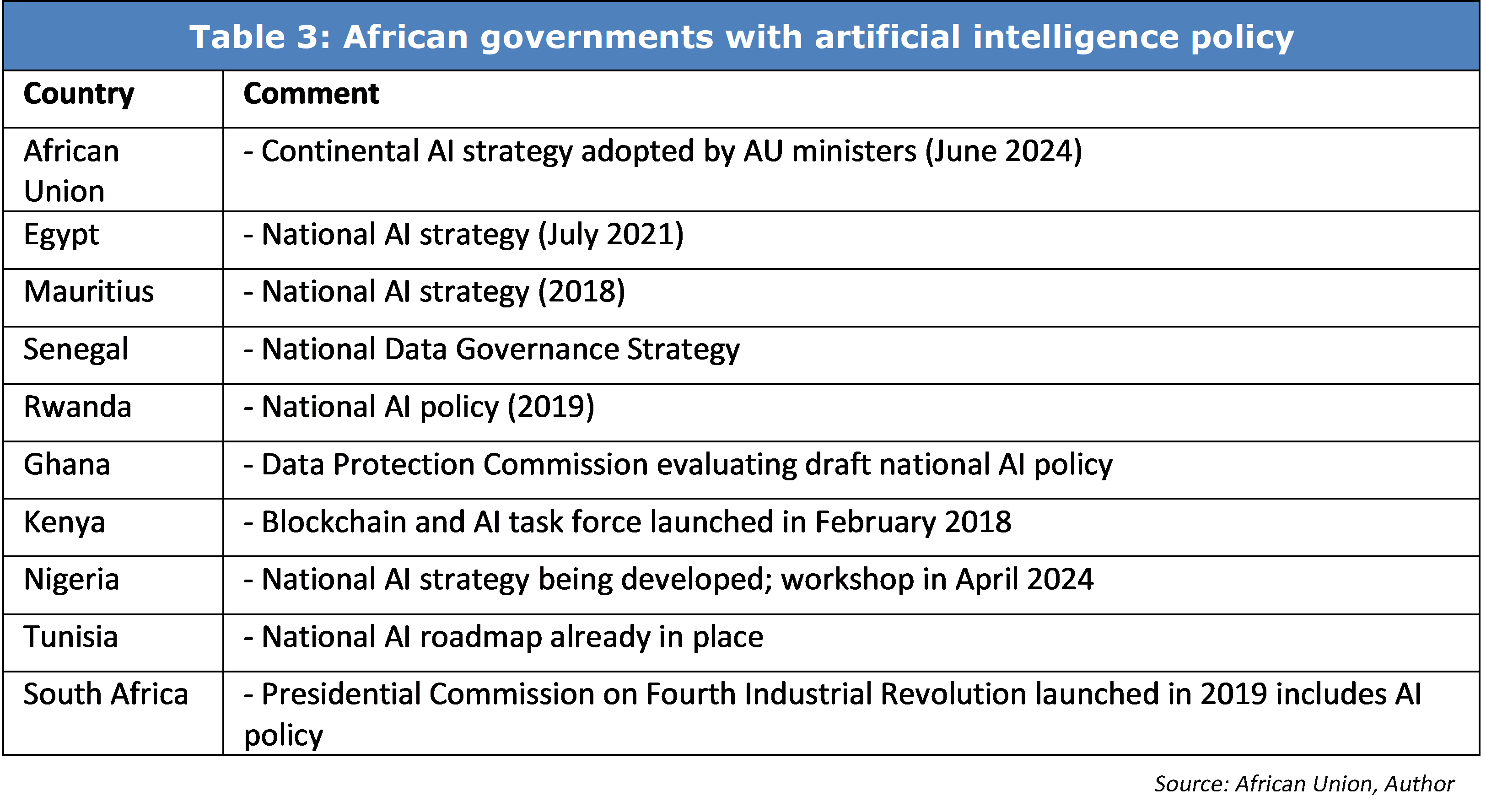

While the focus of African generative AI stakeholders has been on the inclusion (or availability for inclusion) of local African languages in generative AI models, a hitherto overlooked issue of how educated Africans use the English language to communicate, which though highly proficient but tends to come across to native English speakers as highfalutin, deserves attention. Like well-educated Africans, generative AI models trained with the English language answer queries in highly standard English; which is just as well. The dilemma emerges when an educated African’s creative output is confused with that of a generative AI model. This is no trifling matter, as a highly spirited social media debate involving Paul Graham, a prominent Silicon Valley entrepreneur and computer scientist, and mostly Nigerian respondents in April 2024, in what some termed “lexical racism”[36], shows.[37] The evolving African AI governance landscape (see Table 3) should make these considerations a priority.

While the focus of African generative AI stakeholders has been on the inclusion (or availability for inclusion) of local African languages in generative AI models, a hitherto overlooked issue of how educated Africans use the English language to communicate, which though highly proficient but tends to come across to native English speakers as highfalutin, deserves attention. Like well-educated Africans, generative AI models trained with the English language answer queries in highly standard English; which is just as well. The dilemma emerges when an educated African’s creative output is confused with that of a generative AI model. This is no trifling matter, as a highly spirited social media debate involving Paul Graham, a prominent Silicon Valley entrepreneur and computer scientist, and mostly Nigerian respondents in April 2024, in what some termed “lexical racism”[36], shows.[37] The evolving African AI governance landscape (see Table 3) should make these considerations a priority.

Africa should focus on open-source, localized, and distributive generative AI

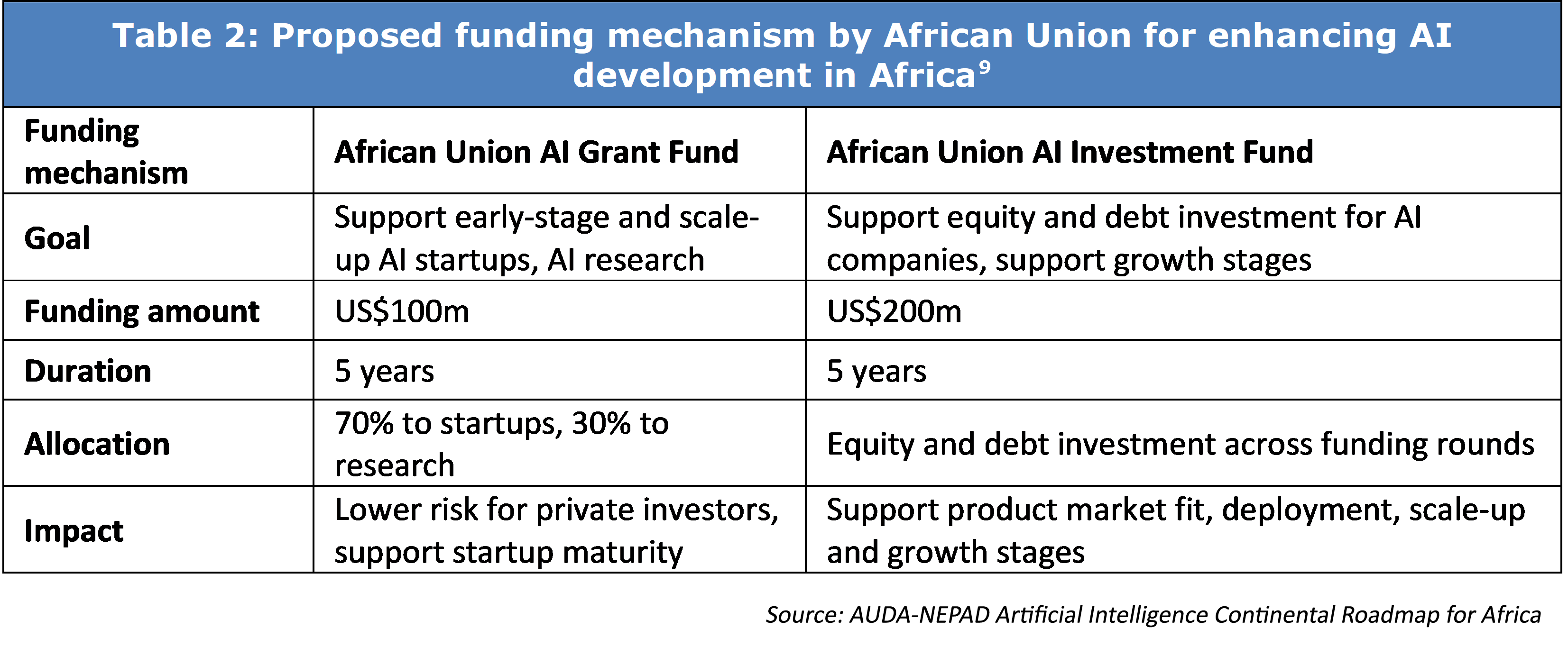

Generative AI will be ubiquitous, but ironically centralised, as the cloud, which is already dominated by just a few global tech firms, will almost entirely power it. Africa’s infrastructural deficit will constrain the continent’s ability to control the ownership of its data. As African governments have been playing catch-up, with artificial intelligence, especially generative AI, which is evolving very rapidly, their governance response risks being overly restrictive and generalised or ill-fitting, owing to competence limitations. A concerted continental effort, which is already underway, could prevent such missteps. African ministers adopted the AU’s Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy, as well as an African Digital Compact in June 2024.[38] Beyond policy, African tech startups will need help with capital to enable them establish Africa’s stake in global AI. The African Union has proposed a mechanism for facilitating financing for such entrepreneurial efforts (see Table 2), although African generative AI startups have had mixed results thus far.

Gro Intelligence, one of the most prominent of such generative AI ventures, which focused on agricultural and climate forecasting with AI, failed in early 2024, for instance, after financing dried up, exemplifying how the challenge ahead for generative AI’s evolution on the continent will extend beyond just legacy infrastructure, but scale and patient capital that waits for expected scale economies to materialise, as well.[39] Awarri, a Nigerian AI startup backed by the government to develop large language model for Nigerian languages, is another example, as it is already courting controversy over propriety, governance and ownership, since public funds are being used to finance a private entity to produce a supposedly public good, without a clear indication on ownership of the data that is being used to train their model or in fact the ownership of the model itself.[40] Still, there is clearly a need for an “Africanised” generative AI; that is, one that applies the accurate context to African data and African consumers. As visualised in Figure 2, we recommend the following towards this goal:

Gro Intelligence, one of the most prominent of such generative AI ventures, which focused on agricultural and climate forecasting with AI, failed in early 2024, for instance, after financing dried up, exemplifying how the challenge ahead for generative AI’s evolution on the continent will extend beyond just legacy infrastructure, but scale and patient capital that waits for expected scale economies to materialise, as well.[39] Awarri, a Nigerian AI startup backed by the government to develop large language model for Nigerian languages, is another example, as it is already courting controversy over propriety, governance and ownership, since public funds are being used to finance a private entity to produce a supposedly public good, without a clear indication on ownership of the data that is being used to train their model or in fact the ownership of the model itself.[40] Still, there is clearly a need for an “Africanised” generative AI; that is, one that applies the accurate context to African data and African consumers. As visualised in Figure 2, we recommend the following towards this goal:

- Ensure appropriate compensation and contextualisation of African data

African governments should view the data and creative content of their citizens the way they do mineral resources. They are economic assets and should be paid for. - Build and support sovereign African clouds

Even as global tech firms will likely maintain their dominance of the cloud, African governments and firms should build and support local data centres for data provenance and backup repository purposes at least.

- Develop generative AI applications for African needs and problems

As computing hardware for generative AI is already far advanced for African participation, African stakeholders should focus on generative AI applications that address African developmental priorities instead.

References

[1] Google (n.d). Generate text, images, code and more with Google Cloud AI. Retrieved from https://cloud.google.com/use-cases/generative-ai

[2] Criddle, C. & Murgia, M. (2024, May 20). Artificial intelligence companies seek big profits from ‘small’ language models. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/359a5a31-1ab9-41ea-83aa-5b27d9b24ef9

[3] Bradshaw, T. (2024, January 4). Cristiano Amon: generative AI is ‘evolving very, very fast’ into mobile devices. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://on.ft.com/3RDwJLq

[4] Raji, R. (2022, September 15). Where is Africa in the cloud? Nanyang Technological University. Retrieved from https://www.ntu.edu.sg/cas/news-events/news/details/where-is-africa-in-the-cloud

[5] Waters, R. (2023, December 28). Media and tech war over generative AI reaches new level. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://on.ft.com/3THY1D8.

[6] Adams, R., et al. (2023, October 6). A new research agenda for African generative AI. Nature Human Behaviour, 7, pp. 1839-1841. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-023-01735-1

[7] Schacht, K. (2023, July 29). Bridging the AI language gap in Africa and beyond. DW. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/bridging-the-ai-language-gap-in-africa-and-beyond/a-66331763

[8] Knibbs, K. (2024, January 10). Congress Wants Tech Companies to Pay Up for AI Training Data. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/congress-senate-tech-companies-pay-ai-training-data/

[9] African Union Development Agency (2023). White Paper: Regulation and Responsible Adoption of AI in Africa Towards Achievement of AU Agenda 2063. AUDA-NEPAD: Johannesburg, South Africa. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/drive/mobile/folders/11dHIWW-q4E6FYDinkyDUCdJGG5FDApos?usp=sharing&trk=article-ssr-frontend-pulse_little-text-block

[10] Kinya, W. (2023, November 8). Bringing Search Labs and generative AI in Search to Sub-Saharan Africa. Google Africa Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.google/intl/en-africa/company-news/technology/bringing-search-labs-and-generative-ai-in-search-to-sub-saharan-africa/

[11] Gilbert, D. (2024, February 22). Google’s ‘Woke’ Image Generator Shows the Limitations of AI. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/google-gemini-woke-ai-image-generation/

[12] Is Google’s Gemini chatbot woke by accident, or by design? (2024, February 28). The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/united-states/2024/02/28/is-googles-gemini-chatbot-woke-by-accident-or-design

[13] Wiggers, K. (2024, May 15). Google still hasn’t fixed Gemini’s biased image generator. TechCrunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2024/05/15/google-still-hasnt-fixed-geminis-biased-image-generator/

[14] Why AI needs to learn new languages (2024, January 24). The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2024/01/24/why-ai-needs-to-learn-new-languages

[15] Risemberg, A. & Dosunmu, D. (2024, February 28). The AI project pushing local languages to replace French in Mali’s schools. Rest of World. Retrieved from https://restofworld.org/2024/mali-ai-translate-local-language-education/

[16] Ojenge, W. (2023, March 18). Lack of Africa-specific datasets challenge AI in education. University World News. Retrieved from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post-mobile.php?story=20230315141216454

[17] Komminoth, L. (2023, January 27). Chat GPT and the future of African AI. African Business. Retrieved from https://african.business/2023/01/technology-information/chat-gtp-and-the-future-of-african-ai

[18] Thomson Reuters Foundation (2024, February 8). Singapore builds ChatGPT-alike to better represent Southeast Asian languages, cultures. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3251353/singapore-builds-chatgpt-alike-better-represent-southeast-asian-languages-cultures

[19] Aro, B. (2024, April 20). FG launches local language model for AI development. The Cable. Retrieved from https://www.thecable.ng/fg-launches-local-language-model-for-ai-development/amp/

[20] Semafor (2024, May 10). Thinking Outside the Box on AI: How AI can change education, agriculture and healthcare in India [Video file]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/4Jb9pyulC2w

[21] Heaven, W.D. (2023, December 19). These six questions will dictate the future of generative AI. Technology Review. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/12/19/1084505/generative-ai-artificial-intelligence-bias-jobs-copyright-misinformation/.

[22] Lin, B. (2023, December 29). How Did Companies Use Generative AI in 2023? Here’s a Look at Five Early Adopters. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-did-companies-use-generative-ai-in-2023-heres-a-look-at-five-early-adopters-6e09c6b3

[23] Generative AI holds much promise for businesses (2023, November 13). The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/the-world-ahead/2023/11/13/generative-ai-holds-much-promise-for-businesses

[24] Turk, V. (2023, October 10). How AI reduces the world to stereotypes. Rest of World. Retrieved from https://restofworld.org/2023/ai-image-stereotypes/

[25] Heaven, W.D. (2024, March 4). Large language models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why. Technology Review. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/03/04/1089403/large-language-models-amazing-but-nobody-knows-why/

[26] Schmidt, E. (2024, January 26). How We Can Control AI. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/tech/ai/how-we-can-control-ai-327eeecf

[27] Ryan-Mosley, T., Heikkila, M. & Yang, Z. (2024, January 5). What’s next for AI regulation in 2024? Technology Review. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/01/05/1086203/whats-next-ai-regulation-2024/

[28] Heikkilä, M. (2023, December 11). Five things you need to know about the EU’s new AI Act. Technology Review. Retrieved from https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/12/11/1084942/five-things-you-need-to-know-about-the-eus-new-ai-act/

[29] European Parliament (2024, March 13). Artificial Intelligence Act: MEPs adopt landmark law [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20240308IPR19015/artificial-intelligence-act-meps-adopt-landmark-law

[30] Knight, W. (2024, January 25). Etching AI Controls Into Silicon Could Keep Doomsday at Bay. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/story/fast-forward-ai-silicon-doomsday/

[31] Musoni, M. (2024, January 29). Envisioning Africa's AI governance landscape in 2024. ECDPM. Retrieved from https://ecdpm.org/work/envisioning-africas-ai-governance-landscape-2024

[32] Calderon, J. (2024, February 3). To benefit all, diverse voices must take part in leading the growth and regulation of AI. TechCrunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2024/02/03/to-benefit-all-diverse-voices-must-take-part-in-leading-the-growth-and-regulation-of-ai/

[33] Raji, R. (2022, February 15). Africa wakes up to the potential of artificial intelligence. Nanyang Technological University. Retrieved from https://www.ntu.edu.sg/cas/news-events/news/details/africa-wakes-up-to-the-potential-of-artificial-intelligence

[34] Anthony, A. & Munga, J. (2024, April 16). Africa Has Its Own Approach to AI. World Politics Review. Retrieved from https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/africa-ai-artificial-intelligence-tech/

[35] Wiggers, K. (2024, April 23). Amazon wants to host companies’ custom generative AI models. TechCrunch. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2024/04/23/amazon-wants-to-host-companies-custom-generative-ai-models/

[36] Ale, M. (2024, April 10). The Paul Graham vs Nigerian Twitter Saga; Lexical racism and language bias masked as ChatGPT hysteria. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@moyosoreale/the-paul-graham-vs-nigerian-twitter-saga-lexical-racism-and-language-bias-masked-as-chatgpt-53ee9f6459aa

[37] Bodunde, D. (2024, April 9). Nigerians berate US author Paul Graham for claiming ‘delve’ is only used by ChatGPT. The Cable. Retrieved from https://lifestyle.thecable.ng/nigerians-berate-us-author-paul-graham-for-claiming-delve-is-only-used-by-chatgpt/

[38] African Union (2024, June 17). African ministers adopt landmark Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy, African Digital Compact to drive Africa’s development and inclusive growth [Press release]. Retrieved from https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20240617/african-ministers-adopt-landmark-continental-artificial-intelligence-strategy

[39] Onukwue, A. (2024, June 4). A Kenyan agri-data startup tipped to underpin global food security shuts down. Semafor. Retrieved from https://www.semafor.com/article/06/04/2024/kenyan-ai-data-gro-intelligence-startup-shuts-down

[40] Dosunmu, D. (2024, June 13). A little-known AI startup is behind Nigeria’s first government-backed LLM. Rest of World. Retrieved from https://restofworld.org/2024/nigeria-awarri-ai-startup-llm/