GUUD facilitates trade in Africa

The story of a Singaporean firm that integrated customs clearance processes across five countries

By Jaco Maritz

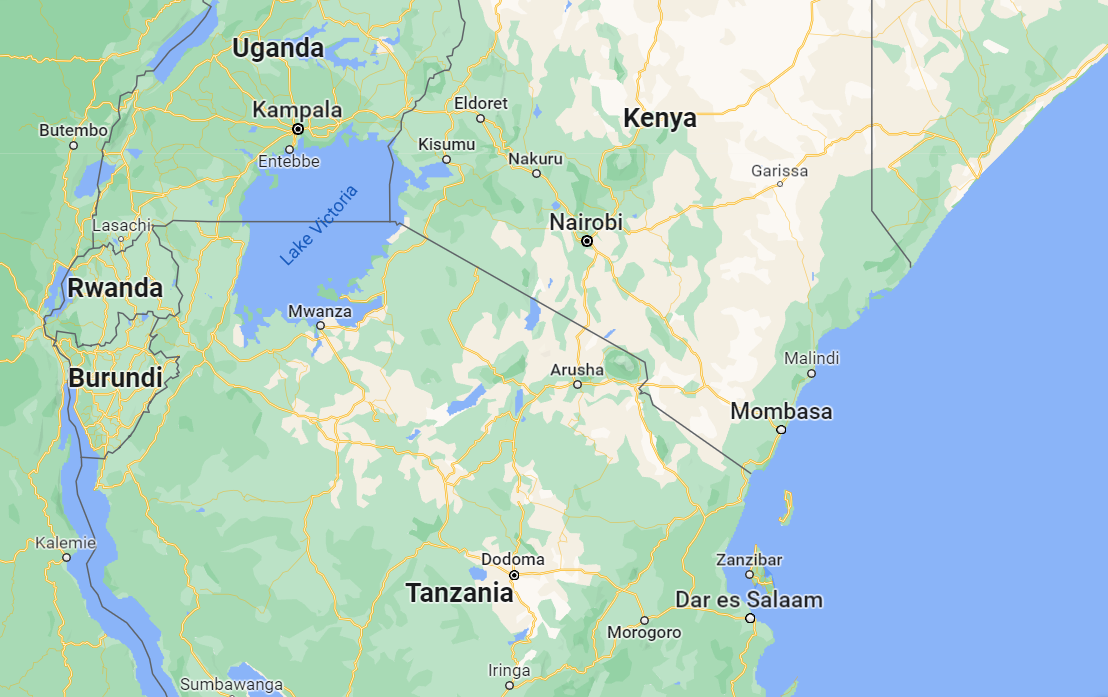

Every day, hundreds of containers of cargo destined for the landlocked countries of Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi enter through the ports in Kenya and Tanzania. These five nations are all part of the East African Community, which launched the single customs territory in 2013. It is intended to simplify trade between the member states and slash costs by clearing shipments at their first port of arrival or departure, but inefficient flows of customs information have handicapped its effectiveness. Up until recently, importing cargo and moving it between member states required traders to submit a slew of documents – including shipping records, invoices, permits and certificates – to the respective customs authorities in each country.

For instance, if a Rwandan importer wanted to bring in a consignment from China through the port of Mombasa in Kenya, and then transported overland via Uganda, it would have to submit paperwork to not only the Rwanda Revenue Authority but also to its counterparts in Uganda and Kenya. If the importer didn’t have a presence in Uganda and Kenya, it had to pay someone to physically submit the required documents at the offices of the relevant government agencies, a costly and time-consuming process.

Singapore-headquartered trade technology company GUUD, founded by entrepreneur Desmond Tay, has, however, streamlined this whole process through the implementation of a Single Customs Territory platform which integrates customs clearance processes across the five countries. All the documentation is now shared digitally between the various revenue authorities, ports and border posts. With GUUD’s system, an importer in Rwanda therefore only needs to submit the relevant documents to their local authorities, and it is then shared with the relevant agencies in all the other countries. “This project helped to cut down a lot of the time previously required for import-export clearance,” explains Tay.

Entrepreneurial foundations

Born in Singapore, Tay says he grew up in an “average Singaporean household, living a simple life”. His father was a policeman and his mother helped out in a restaurant. During school vacations, Tay took on part-time jobs working in a car wash and as a salesman in a department store. He graduated from Ngee Ann Polytechnic with an electrical engineering diploma. After serving his time in the army (national service in the armed forces is mandatory for all Singaporean men), he started his career at an engineering company specialising in factory automation. Once Tay completed a subsequent computer science degree, he moved on to an IT company currently known as CrimsonLogic that specialises in e-government solutions. The experience at CrimsonLogic would come in handy later in Tay’s career: one of the projects he worked on while at the company in the late 1990s was to implement a digital trade facilitation system in Mauritius.

Tay got his first taste of what it's like to be an entrepreneur when he joined his previous boss at CrimsonLogic on a new venture, which built online platforms for financial institutions. “I was the first employee at that company, so essentially I was doing everything from programming to helping out with sales and a lot of other stuff.”

A few years later, in 2003, Tay took the plunge and started his own business. In the beginning, the focus was on developing enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, like sales and inventory management products, for small- and medium-sized businesses. The company was providing software-as-a-service solutions before it became mainstream. Tay eventually pivoted the company to building software for governments, a field he was familiar with from his time at CrimsonLogic. He admits that he found developing ERP solutions “boring” and that digitising government systems had a much greater impact.

One of the projects the company was involved in was the digitalisation of Singapore’s air cargo processes. After this assignment, Tay decided to focus specifically on building trade and logistics solutions. “That project made us realise there are a lot of opportunities in the area of trade and logistics. Air cargo is just one part of the ecosystem. From there we started to look into different parts of the ecosystem.”

Today the company employs close to 200 people with offices located in Singapore, China, Indonesia and Kenya, and projects spanning more than 17 countries.

Entering the African market

GUUD’s first African project was in Mauritius, where it upgraded the TradeNet digital trade facilitation system, a project Tay was involved with all those years ago at CrimsonLogic. “The operator of TradeNet in Mauritius wanted to upgrade the system and contacted us. That project gave us an initial footprint in Africa,” he says.

The TradeNet platform allows traders, customs brokers, shipping agents, and freight forwarders to submit trade documents like manifests, declarations, certificates of origin, import/export permits to various authorities. Commercial banks are also linked, enabling electronic payment of duties and taxes. The benefits of TradeNet have been to greatly reduce trade declarations processing times, minimise travelling, and eliminate duplication of information capture by different agencies. “When I initially worked on the project in the 1990s, the internet was still in its infancy. The software had to be installed on a PC. We came in and replaced the system with up-to-date technology,” Tay explains.

After completing the project in Mauritius, GUUD started scouting for other projects in Africa. It registered a company in Kenya, and appointed a Singaporean general manager. The Kenyan office’s first big win was the Single Customs Territory project for the East African Community (EAC). Tay says GUUD landed the work by pitching its solution to the EAC Secretariat. Once it landed the project, the company began to build its team through local hires.

Workshop for Single Customs Territory (SCT) Project – Attendees from Kenya Revenue Authority, Tanzania Revenue Authority, Uganda Revenue Authority, Burundi Revenue Authority, Rwanda Revenue Authority, Kenya Port Authority.

Workshop for Single Customs Territory (SCT) Project – Attendees from Kenya Revenue Authority, Tanzania Revenue Authority, Uganda Revenue Authority, Burundi Revenue Authority, Rwanda Revenue Authority, Kenya Port Authority.

Executing the East African Single Customs Territory project was anything but straightforward as GUUD had to link the systems of five countries that all had different levels of digitisation, and varying requirements for customs documentation. The project took about a year to implement before it went live. GUUD is currently in the process of developing the second phase, which involves integrating tools such as cargo scanners with the customs systems and linking with logistics operators.

West Africa and beyond

Over the years, GUUD has been involved in several other projects in Africa. In the West African nation of Togo it introduced a digital trade certification system. “Exporters need certain certifications in order to export their products. In Togo, these were all issued through a very manual process. Exporters went through the whole application process, including laboratory testing of their products, and eventually a paper certificate was issued. This system was open to fraud. Together with the Togolese government we looked at this whole certification process. First of all we brought it online so that people don’t have to go to government agency offices to apply for the certificates. We also brought in the concept of digital certificates. So apart from the paper certificate, a digital certificate is also issued,” Tay says.

GUUD landed the Togo project after identifying inefficiencies in Togo’s trade system and then presenting a solution to the government. “Togo is helping their producers to export their products overseas. One of the key aspects to export more is assuring buyers of the quality of products, and certification plays an important role in that. We spoke to the government and then we pitched them the idea of a national e-certificate platform.”

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could potentially also open up opportunities for GUUD. AfCFTA, which in theory officially came into effect in 2021, will bring together a market of more than a billion people but is yet to be fully implemented on individual country level. The agreement aims to boost intra-Africa trade by 52%, with the World Bank estimating AfCFTA could lift 30 million people from extreme poverty and 68 million from moderate poverty. “We are closely monitoring AfCFTA and have spoken to a few organisations about how it will impact intra-African trade. However, at this point AfCFTA is largely conceptual and it will take some time to gain traction. But we don’t want to miss out on a good opportunity,” Tay says.

Operating in Africa requires patience, particularly when dealing with governments, according to Tay. “In Asia we tend to be quite impatient. However, doing business in Africa takes a lot of patience because creating trust and understanding with our clients is very important. Culturally we are different, the way we do things are different. So it requires a lot of patience from both sides in order to understand one another.”

As to not waste its time running after dead ends, GUUD typically looks for the “buy-in” from senior officials before it will go all out to pitch its solutions to a particular government. “You need to have the endorsement from a senior government official who sees the value of bringing in digitalisation. Without their endorsement you will just run around in circles without getting anywhere.” Tay adds it is important to establish if governments have the budget for these projects, and if they don’t, if it can be funded by donors.

GUUD also works closely with organisations like the Singapore Cooperation Enterprise (SCE), Enterprise Singapore, USAID and TradeMark East Africa. For instance, Enterprise Singapore helped GUUD to engage with private sector stakeholders for a project in Mauritius, while SCE has assisted with government-related business in places like Djibouti. “These are very good partners because they have contacts in governments and they know which projects are serious and which ones we should probably not waste our time on. Working with the right partners in Africa is very important. It is not just about culture but understanding the market itself, because each of Africa’s 54 countries is different,” Tay notes.

Together with TradeMark East Africa (donor for the SCT project) – from left to right, Edward Ichunghwa (ICT Director, TMEA), Desmond Tay (CEO, GUUD), Alban Odhiambo (Senior Director for Trade, TMEA) and George Chan (GM Africa, GUUD)

Together with TradeMark East Africa (donor for the SCT project) – from left to right, Edward Ichunghwa (ICT Director, TMEA), Desmond Tay (CEO, GUUD), Alban Odhiambo (Senior Director for Trade, TMEA) and George Chan (GM Africa, GUUD)

He highlights language as another challenge in certain markets. “In Singapore we are more fluent in English, so typically anglophone African countries are easier for us to navigate. French-speaking countries are always a challenge in terms of communication. For example, in countries like Togo and Djibouti you can’t survive without a translator. However, we do have some French-speaking staff.”

Financing African trade

Apart from implementing systems for governments, Tay also wants to launch some of the company’s private sector-focused solutions in Africa. Its trade finance products, for example. Trade finance is an essential element of global trade. By involving commercial banks in the transaction, sellers and buyers mitigate against the risks of not getting paid or the cargo not arriving. “Trade finance instruments are premised on an existing credit relationship between counterparty banks. As such, trade finance is essential to cross-border payments, and even more so during crises, when both real and perceived cross-border risk increases while, simultaneously, much-needed capital and liquidity can dry up from the financial sector on both sides of the border,” notes the IFC.

According to an African Development Bank report, participation in trade finance activities on the continent by banks has decreased over the previous decade, leading to an estimated trade finance gap of US$82 billion in 2019. “Competition, new banking regulations on know-your-customer/anti-money laundering, and strict capital requirements introduced after the global financial crises have increased due diligence costs and decreased margins, making small transactions, particularly for SMEs, unprofitable for banks,” reads the document.

In Singapore, GUUD has built a multi-bank trade finance portal, called RYTETFAP, which provides a full suite of trade financing application options for businesses. Instead of physically couriering documents such as bills of lading and invoices to banks when applying for trade finance, importers and exporters can complete the entire process online.

The company has introduced the concept of transaction-based trade finance, where the credit is extended using the cargo as collateral as opposed to making creditworthiness decisions based on a business’ balance sheet and cash flows. “If something happens, and the importer defaults on his payment, we are able to recover the money by selling the cargo,” Tay explains. He says with this approach, new sources of trade financing, apart from traditional banks, can be brought in, and businesses that in the past would not have been approved by the banks can receive credit. “We have been operating on this model of trade finance for the past two-and-a-half years – financing products like coffee, palm oil, seafood and milk powder – and it has proven successful. We can bring this to Africa. For instance, we are currently talking to partners regarding importing building materials into Mozambique using this trade financing concept.”

Online marketplaces

GUUD has developed Singapore’s first online business-to-business (B2B) seafood marketplace that helps traders sell their goods more effectively. Tay believes there is potential for similar platforms in Africa, and the company is already in discussions with stakeholders in several West and Southern African countries with large fishing industries.

GUUD’s marketplaces are differentiated from platforms like Alibaba, in that they target specific industries. “Our take on B2B platforms is to focus on an industry and then bring all the stakeholders in that industry together and create a community.”

In addition to connecting buyers and sellers, GUUD integrates the entire ecosystem – including the certification process and logistics – into its marketplaces. “Seafood trade is not as simple as someone sells the fish and someone buys the fish. For example, supplying seafood to a retail chain is very different from selling seafood to a processing plant that makes fish filet or fish fingers. There are also different stakeholders for farmed seafood versus wild caught seafood. Likewise for logistics – there is frozen seafood, there is fresh seafood, there is live seafood and all of these have different logistics requirements,” Tay explains.

Beyond seafood, he sees potential for similar marketplaces for various other commodities. For instance, GUUD is working on launching a marketplace for the coffee industry.

Overall, Tay is upbeat about the future of Africa-Asia commerce. “One of our company’s focus areas is to connect trade between Africa and Asia. This is why we are pushing for platforms like the seafood and coffee marketplaces in both Asia and Africa. We want to connect the two continents together.”

According to the African Import-Export Bank, the growing trade ties between Africa and Asia reached a turning point in 2018, when Asia’s share of Africa’s exports reached 27%, exceeding for the first time the share of Africa’s exports to Europe.

“From a long-term perspective, we believe trade between Asia and Africa has a lot of potential and will continue to grow. Agricultural commodities, especially, are big in Africa and Asia has growing consumption. There will be a lot of opportunities in this area,” Tay adds.

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)