How Asia is driving the mining boom in Guinea

Unpacking the outsize role of Simandou in the growth and development of a rising West African Republic

By Bernabe Sanchez*

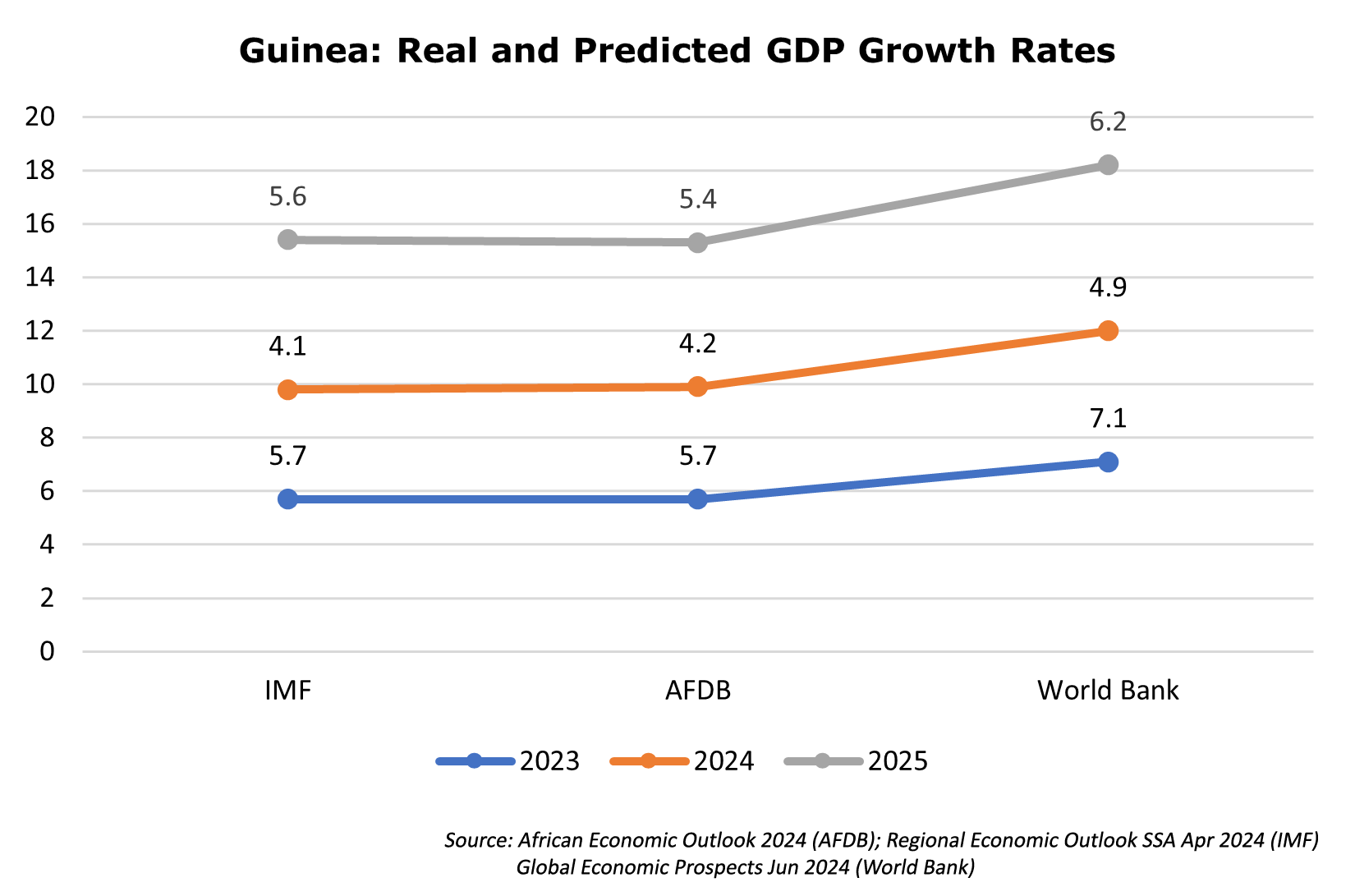

Guinea has become one of the fastest growing economies the world. Its growth has been driven by a mining boom. Following a ban on raw ore exports by Indonesia in 2014, miners of bauxite - the ore needed for aluminium production, turned their attention to Guinea. Since then, bauxite production has grown six-fold.

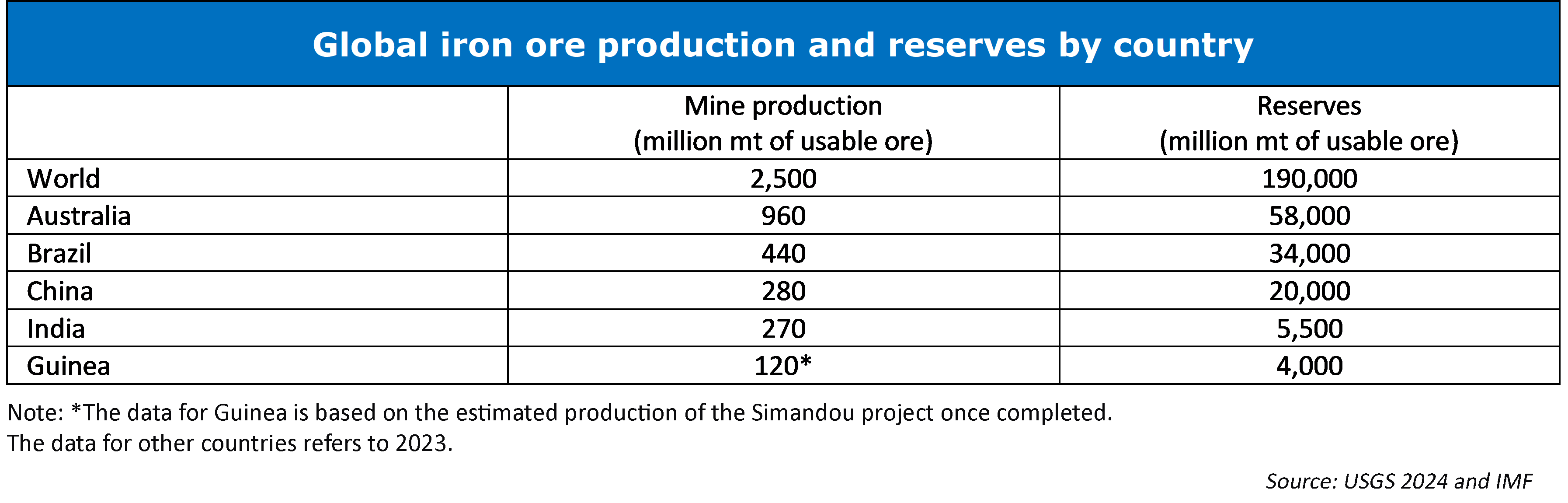

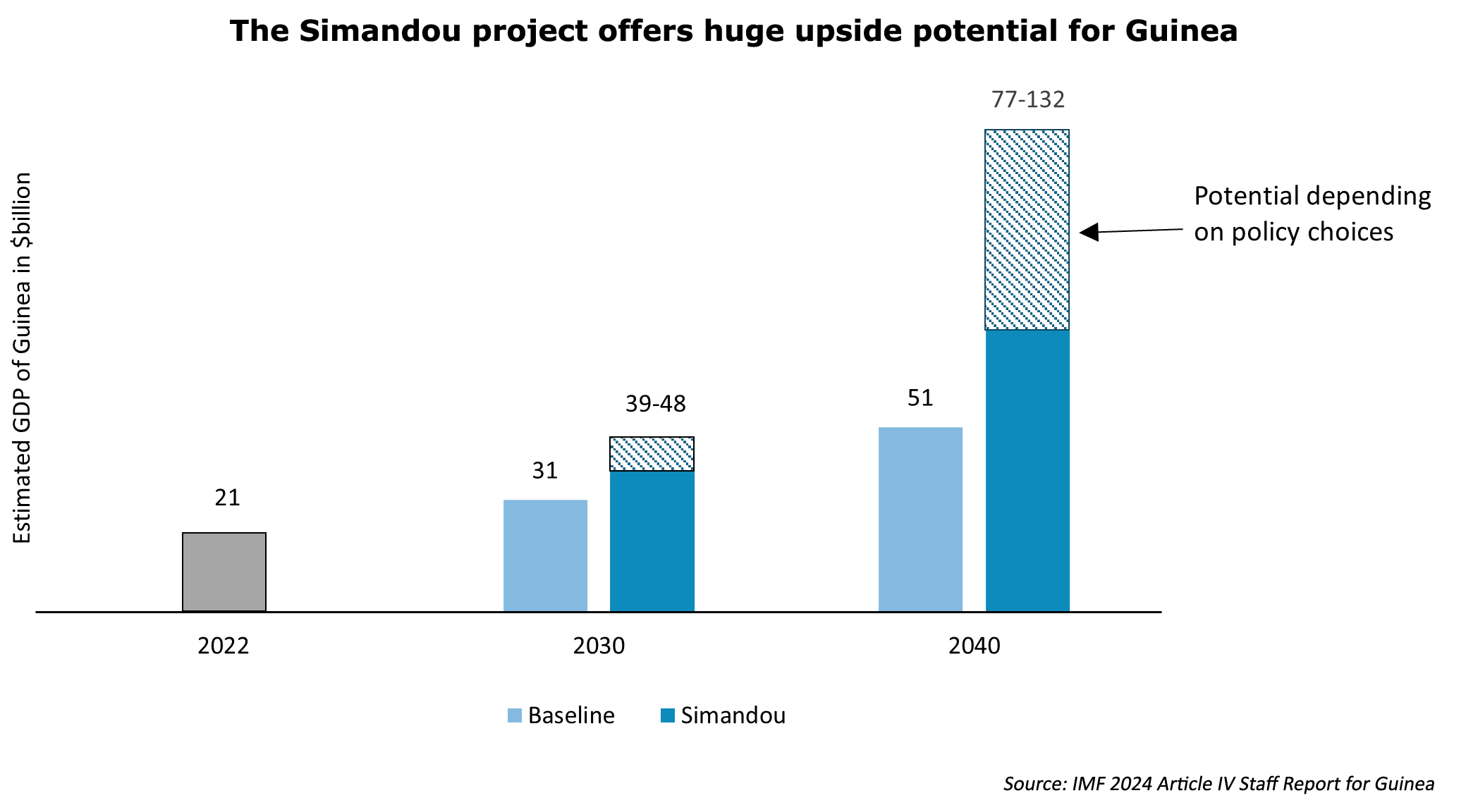

The mining sector accounts for 21% of the GDP and 90% of exports. The country has the largest bauxite reserve in the world, which it has been mining for over 70 years. Yet, 43% of the Guinean households live in poverty. But they have something the world desperately wants. On a 110kms hill range is Simandou - a massive reserve estimated to contain over four billion tons of high-grade iron ore - the largest in the world. If production begins on the US$20bn Simandou iron ore project next year (2025) the real GDP of Guinea could be at least 26% higher by 2030 than what it is expected to be otherwise. It would make Guinea the fifth largest producer of iron ore in the world (IMF, 2024). Simandou could potentially change the economic trajectory of this impoverished West African republic.

Background

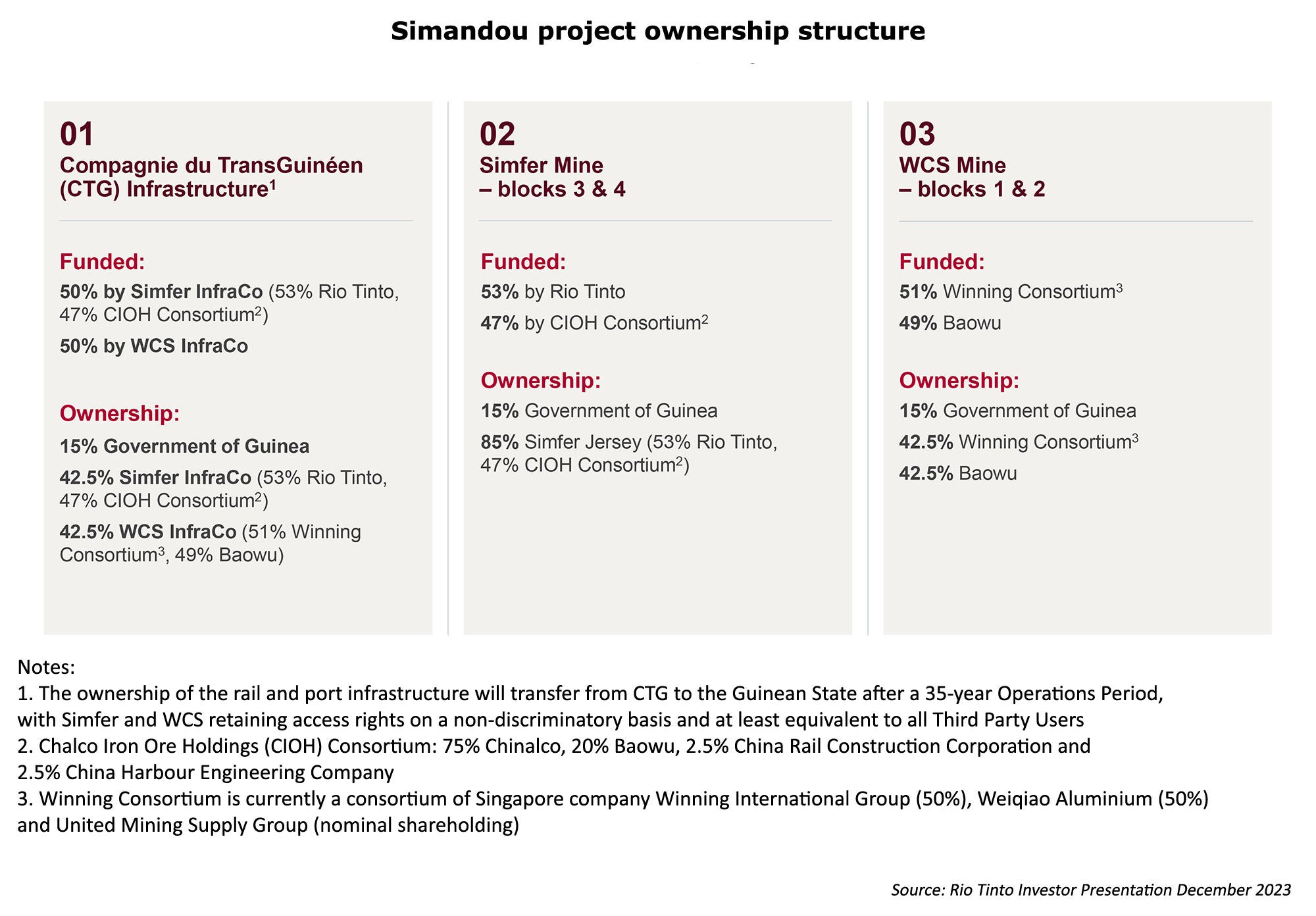

In 2019 the lead investor in the bauxite expansion, Singapore-based Winning International Group, was awarded the rights to develop the northern concession of the stalled Simandou project. Winning’s involvement unlocked the required rail and port investment and now both Winning and Rio Tinto are expecting first production by the end of 2025 and the first export in the beginning of 2026.

What makes Simandou attractive is the richness of its iron ore. High grade iron attracts a premium in the market because making steel from it is less carbon intensive. Chinese demand for steel (in 2023 China produced over 1 billion tonnes of steel - more than half the global output) and the world’s need to decarbonise that industry guarantees a long-term market for the high grade iron ore produced by Simandou (World Steel Association, 2024).

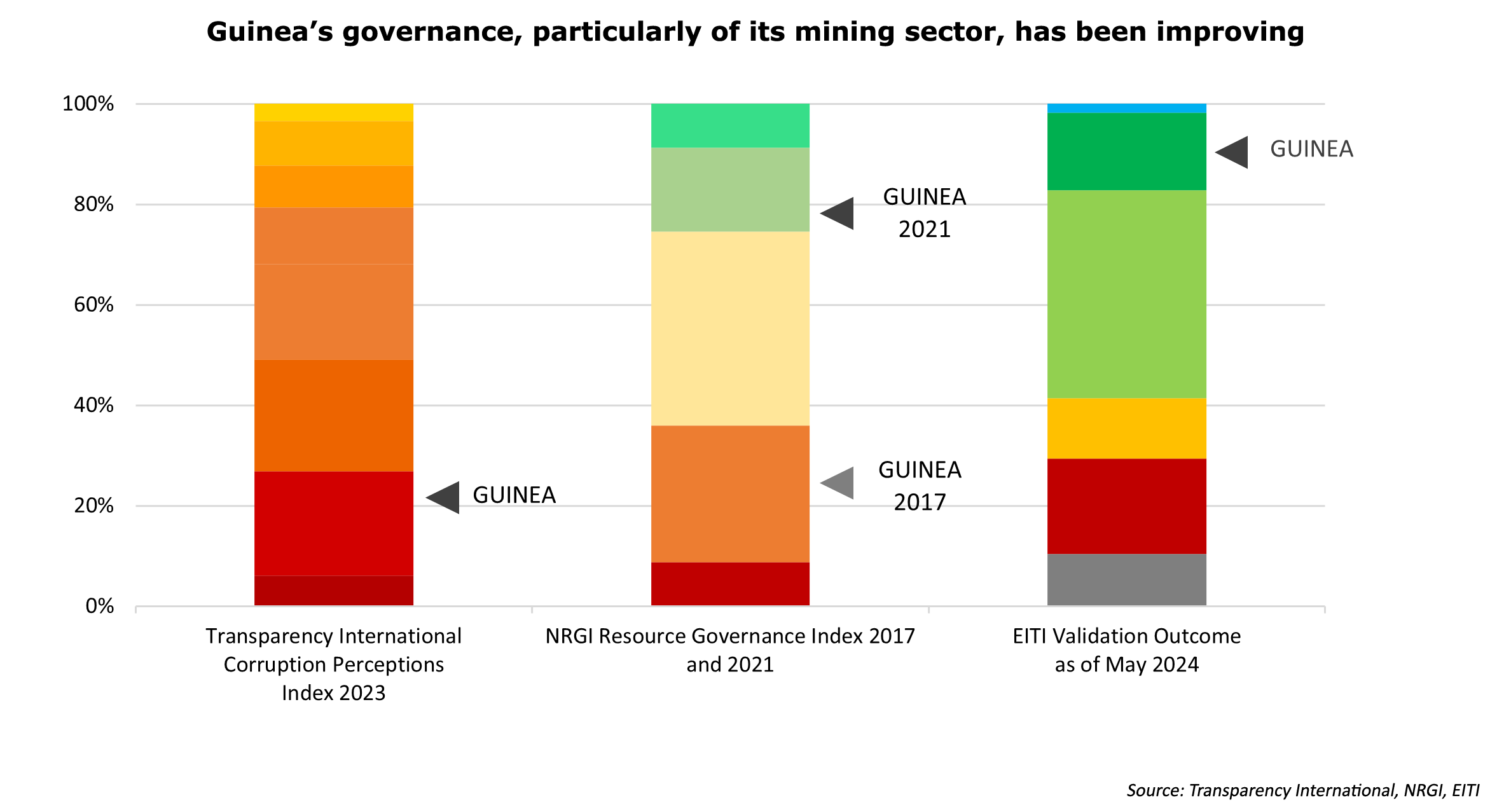

The perception thus far has been that the mining boom has not benefited the average Guinean. There is an opportunity to change the narrative in this new phase of the mining boom. The Simandou project is as large as all investment in the country since 2015 combined, its footprint covers the entire length of the country, and maximising the impact is a top policy priority for the authorities through the development of the Simandou Vision 2040. The right foundation blocks are also in place, with Guinea being well placed in terms of the governance of its mining sector according to internationally recognised institutions such as the NRGI and the EITI.

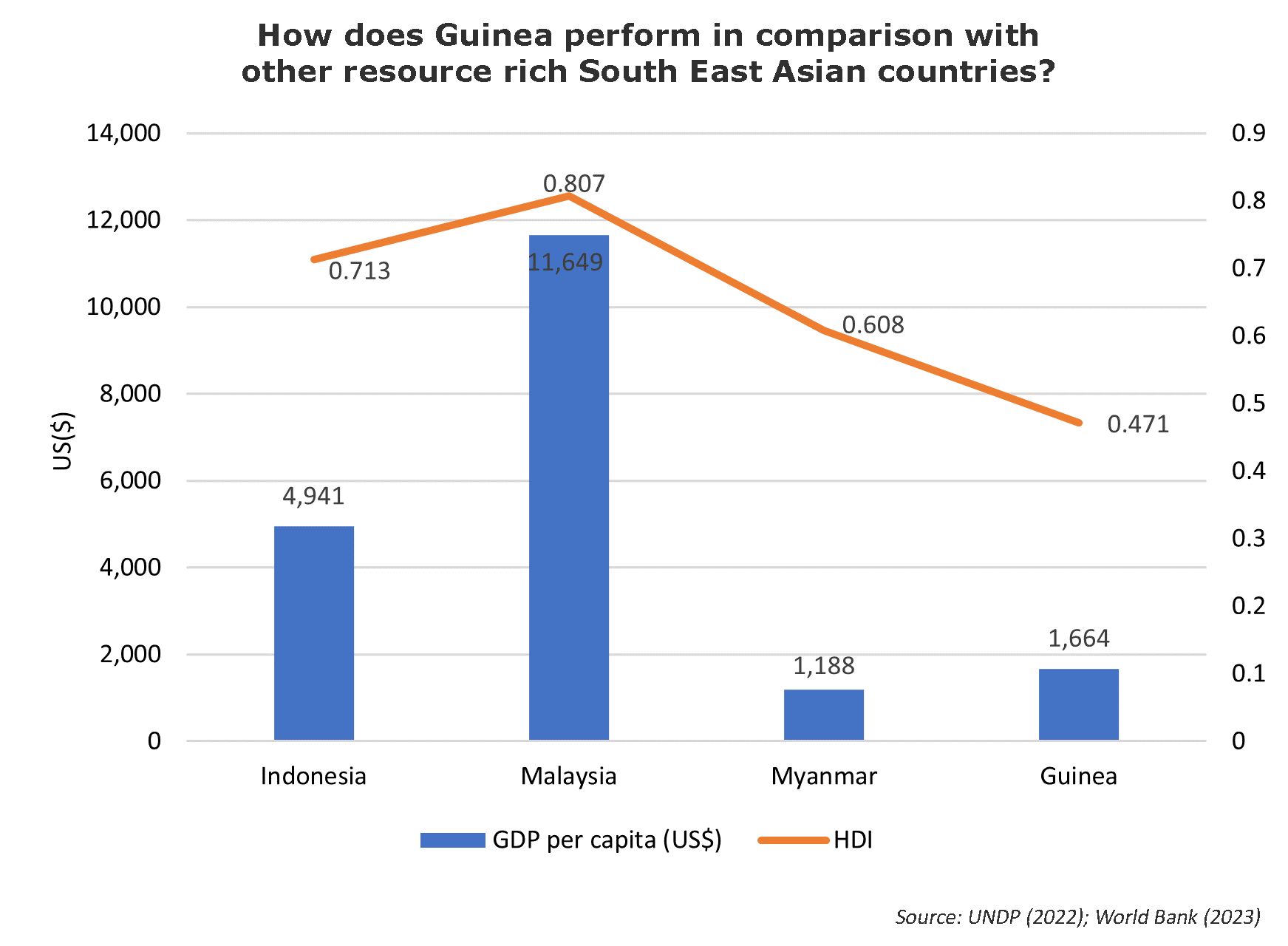

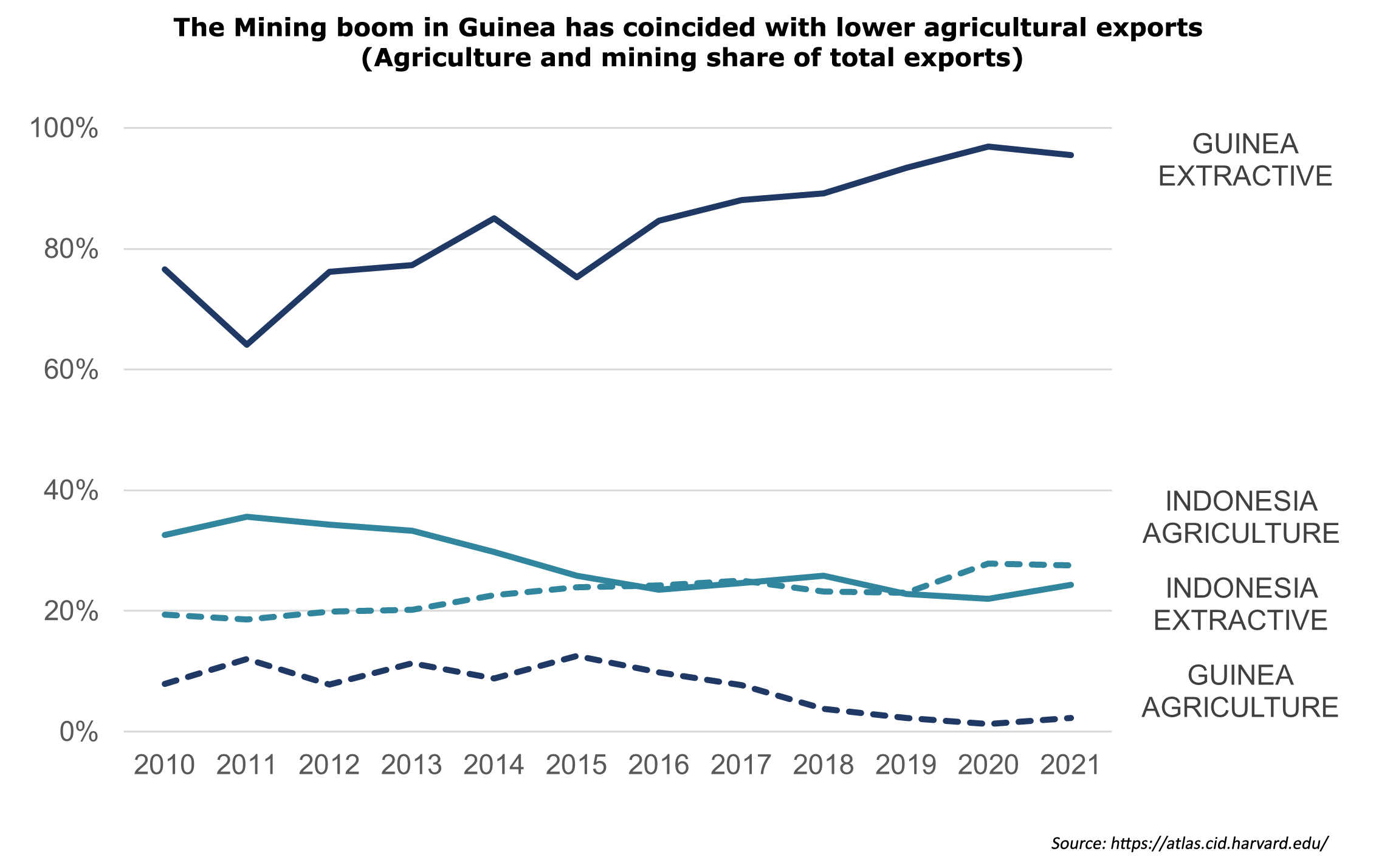

However, the challenge should not be underestimated. Firstly, Guinea has the 12th lowest level of human development globally, lower than many of its poorer neighbours (UNDP, 2024). Secondly, the mining boom has led to a less diversified economy. Guinea now ranks 2nd lowest on Harvard University’s Economic Complexity Index (Harvard Growth Lab, 2024).

Just as policy decisions, investment, and demand from South-East Asia and China has driven the mining boom there is potential for economic collaboration with the region to contribute to improved outcomes for Guineans. There are existing initiatives for policy dialogue, training and attracting non-mining investment that could be expanded to deliver this goal and ensure Guinea escapes the resource curse.

Guinea and the bauxite mining boom

Guinea has been an unheralded economic growth success story. Over a 10-year period GDP has grown at an average 6.1% per annum (World Bank).

Growth over this period has been driven by the mining sector, particularly in bauxite [BS5] and gold. During this time, it has also faced three shocks - the Covid pandemic, the impact of the war in Ukraine on the food prices and the reduction in aid flows and adverse global reaction to the military takeover of power in Sep 2021 [at US$500m in 2022, aid was 25% lower in real terms than at its pre-COVID peak in 2018 (OECD, 2023)].

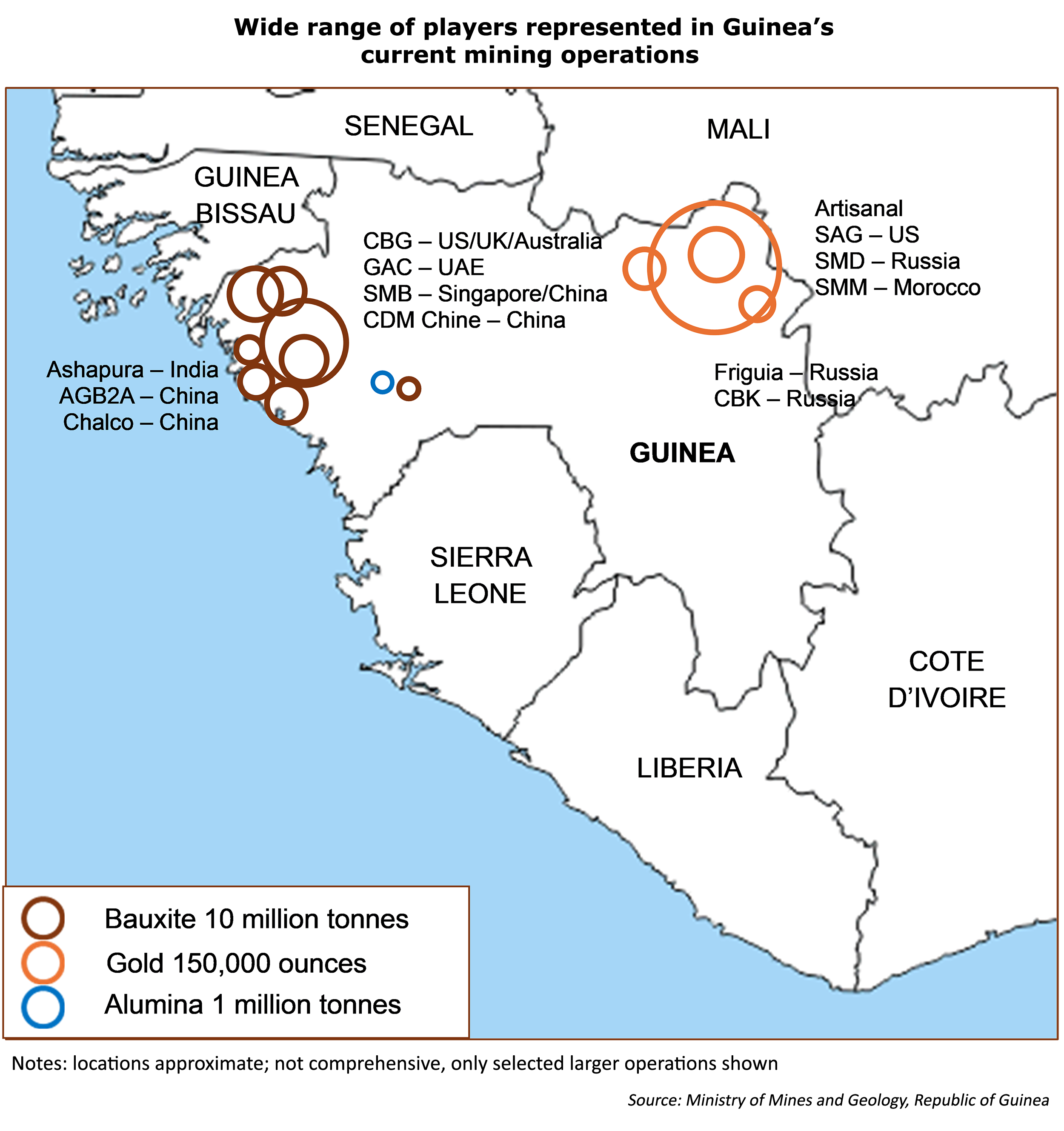

Bauxite production grew from 20 million tonnes in 2015 to 127 million in 2023, taking Guinea past Brazil, China and finally Australia to become the largest producer globally last year. Gold exports grew from 0.6 million ounces in 2015 to 2.5 million in 2023, with new industrial mines opened but with most additional production coming from artisanal small miners (Ministry of Mines and Geology of Guinea, 2018 and 2024).

Bauxite production grew from 20 million tonnes in 2015 to 127 million in 2023, taking Guinea past Brazil, China and finally Australia to become the largest producer globally last year. Gold exports grew from 0.6 million ounces in 2015 to 2.5 million in 2023, with new industrial mines opened but with most additional production coming from artisanal small miners (Ministry of Mines and Geology of Guinea, 2018 and 2024).

Actors in the Guinean mining sector are diverse. This includes Chinese, Western, Russian, Indian and Gulf investors alongside a long tail of local artisanal gold miners.

The main contributor to the bauxite boom is demand from China whose alumina refineries produced 84 million tonnes of alumina in 2023 up from 60 million tonnes in 2015. Less well understood are the internal business and policy drivers that pushed these refineries to source their bauxite as far afield as West Africa. Historically, most bauxite production was captive to nearby refineries: Australian mines supplied refineries in Gladstone and Kwinana; Brazilian mines the refineries in the North of the Country; Chinese mines supplied domestic refineries, with three quarters of capacity located in the northern provinces of Henan, Shanxi, and Shandong.

The main contributor to the bauxite boom is demand from China whose alumina refineries produced 84 million tonnes of alumina in 2023 up from 60 million tonnes in 2015. Less well understood are the internal business and policy drivers that pushed these refineries to source their bauxite as far afield as West Africa. Historically, most bauxite production was captive to nearby refineries: Australian mines supplied refineries in Gladstone and Kwinana; Brazilian mines the refineries in the North of the Country; Chinese mines supplied domestic refineries, with three quarters of capacity located in the northern provinces of Henan, Shanxi, and Shandong.

The Compagnie des Bauxites de Guinée (CBG) was the largest exception to this rule, with it being the cornerstone of the Alcoa and Alcan (now Rio Tinto) Atlantic trade. At the turn of the century CBG exported over 40% of internationally traded bauxite despite its share of total global production being less than 10%. Its production capacity has remained stable at less than 20 million tonnes for decades (CRU, 2023).

Additional investment in expanding capacity further or indeed building a Guinean alumina industry, beyond the relatively small refinery currently operated by Rusal, did not materialise as multinationals prioritised jurisdictions such as Australia and Brazil, which were deemed ‘less risky’ (Campbell, 2010). However, all that was about to change.

First, there was a large expansion of the alumina industry in the coastal Chinese province of Shandong. Only a marginal player in the industry at the start of the century, and far behind the historical powerhouses of Henan and Shanxi, Shandong overtook these two provinces combined last year in alumina production and accounted for almost 20% of all alumina produced globally. As the province lacked any domestic bauxite resources it was built relying on imports, primarily from Indonesia. Imports hit 72 million tonnes in 2013, with more than two thirds of the volume coming from Indonesia.

The second development was the decision by Indonesian authorities to ban exports of unprocessed ore. Chinese bauxite imports from Indonesia went from close to 50 million tonnes in 2013 to zero two year later. Although Malaysia was able to compensate with over 20 million tonnes of bauxite exports to China, it never had the resources to completely offset the loss of imports from Indonesia. So, leading Shandong alumina producer Weiqiao together with its Singapore-based shipping partner Winning International Group decided to double down on the Guinean bauxite mining venture Societé Minière de Boké (SMB), which quickly ramped up to 24 million tonnes of production by 2017.

The third development that supported the continued expansion of Guinea, attracting a plethora of new investors beyond SMB, was the shrinking production of bauxite in China itself. Henan’s production last year (2023) was 9 million tonnes lower than its peak, while mines in Shanxi were producing 15 million tonnes less than at their peak. While the drop in production in Henan was driven by the depletion of economically viable deposits, the situation in Shanxi was primarily due to the mine closures imposed by the authorities on environmental grounds. Thus, business and policy decisions in both China, Indonesia, and Singapore resulted in a remarkable period of high sustained economic growth in far-away Guinea.

Simandou is leading to further growth acceleration over the next few years

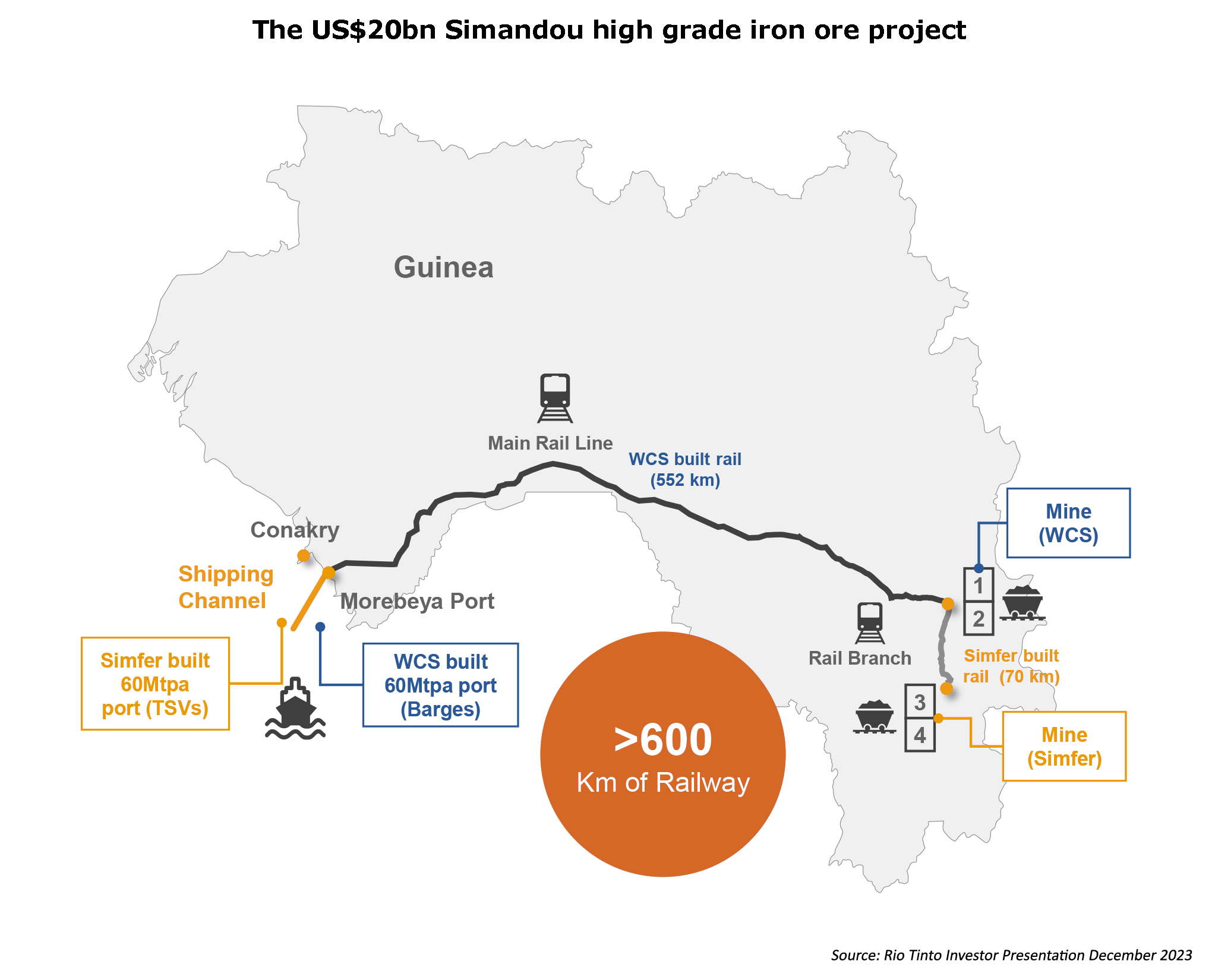

Yet, as good as mining-driven economic growth has been since 2015 the boom is currently entering a new phase of even higher investment and output. Construction of the high-grade iron ore Simandou project is well underway, with the US$20bn scale of the investment matching the total of all other investment in Guinea since 2015.

Simandou is currently the largest unexploited resource of high-grade iron ore in the world at over 4 billion tonnes. Developing the two 60 million tonne mines, over 600km of railway and a 120-million-tonne capacity port to bring the ore to market is currently the largest mining project in the world (Rio Tinto, 2023).

High grade iron ore reduces carbon emissions on standard steel mills (basic oxygen furnace, blast furnace). But more than that, some high-grade iron ore is suitable for direct reduction iron which is the technology that would need to be used to achieve green steel and decarbonise the industry. The planning and development of the project since Rio Tinto defined the resource in 1997 has been fraught. It has faced changes in ownership, global crises, iron ore market busts, corruption scandals and multiple changes in government administration.

The award in 2019 of the northern concession to a consortium led by Winning in a transparent tender signalled the start of the irreversible construction progress we now see. The Winning consortium immediately set to constructing the railway building on their experience having just completed the 135kms bauxite rail line in the northwestern region of Boké.

Winning flies the flag for Singapore in Guinea. Photo courtesy: Winning (2024)

Winning flies the flag for Singapore in Guinea. Photo courtesy: Winning (2024)

Since coming to power in September 2021, the military junta made it a priority to maximise the potential benefit of the infrastructure solution to Guinea as a whole, rather than to any one individual company. First by ensuring that both mines, the Winning-led northern concession and the Rio Tinto-led southern one, would have access on equal terms. Second, by ensuring the rail will allow shared use by other freight and passengers. And third, by guaranteeing a strong role for the government in the governance structure for the newly created Compagnie du TransGuinéen (CTG), which will own the infrastructure upon completion of construction.

As these negotiations took place throughout 2022 and 2023, early construction works continued apace. Both mines are now targeting first production by the end of 2025, with a 30-month ramp up of shipments starting in early 2026.

Guinea just by virtue of its bauxite and gold sectors is already firmly in the top ten of African extractive resource exporters. Once Simandou ramps up to full capacity before the end of the decade, Guinea could overtake the DRC to become the second largest mining country in the continent. In its latest economic assessment of the Guinean economy, published in May 2024, the International Monetary Fund modelled the possible impact of Simandou. It estimates the size of the economy could grow from US$21bn in 2022 to anything between US$39bn and US$48bn in 2030 depending on policy choices. The implied real GDP growth rates are between 8% and 11%.

Guinea just by virtue of its bauxite and gold sectors is already firmly in the top ten of African extractive resource exporters. Once Simandou ramps up to full capacity before the end of the decade, Guinea could overtake the DRC to become the second largest mining country in the continent. In its latest economic assessment of the Guinean economy, published in May 2024, the International Monetary Fund modelled the possible impact of Simandou. It estimates the size of the economy could grow from US$21bn in 2022 to anything between US$39bn and US$48bn in 2030 depending on policy choices. The implied real GDP growth rates are between 8% and 11%.

Translating mining-driven growth into sustainable and inclusive development

Simandou provides an opportunity to change the perspective that mining does not benefit the general population. But grasping the opportunity that Simandou presents requires a good governance framework, not just political will. The encouraging news on this front is that that Guinea has been moving in the right direction. In May 2024 the President Mamadi Doumbouya launched the process to develop Simandou 2040, a new strategic long term development programme for the country.

Guinea climbed six positions up in the 2023 Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. It now ranks 141 out of 180 countries having escaped the bottom 20% of the distribution.

More encouragingly, in the latest Resource Governance Index (released in 2021) published by the Natural Resource Governance Institute Guinea has moved from the category of ‘poor’ governance of the mining sector in 2017 to ‘satisfactory’. The index has three components, with the country scored ‘good’ in the value realization, ‘satisfactory’ in revenue mobilisation, and ‘poor’ in enabling environment.

However, the best governance assessment for Guinea comes from the well-regarded Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI). Based on three components (Stakeholder engagement, Transparency and Outcomes and impact), Guinea now meets the EITI standards to a ‘High’ degree - only one of 10 countries to do so, placing it in the top quintile of the global distribution.

Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that Guinea is still far below where it might be expected to be in terms of human development based on its GDP per capita. If its HDI score was broadly line with expectations, as is the case for Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, it could expect to be ranked about 25 places higher. To take another Asian example, Myanmar, with a lower GDP per capita than Guinea, ranks 37 places higher. A lot of political will and progress on economic governance will be required if the country must meet its expectations. If the scale of the mining opportunity is huge, so are the challenges.

The first challenge is translating GDP growth to human development. Guinea had the 12th lowest score globally in the United Nations’ Human Development Index released in March this year (UNDP, 2024). The good news is that Guinea is outside the bottom 10 for the first time since 2002.

Nonetheless, on human capital Guinea has much progress to make. According to the latest World Development Indicators (WDI) released by the World Bank less than 20% of children in the country can read at a basic level by the time they are ten (11th worst result among countries assessed). The figures for child mortality are worse, with the latest estimates showing 9.6% of children die before their fifth birthday – a rate only surpassed by seven other nations.

Investment in education and health as a percentage of GDP in Guinea is about half the average across the continent, at 3% compared to about 6% (IMF, 2023). The IMF estimates that the additional revenue generated by the government from Simandou will be equivalent to 3% of GDP until 2040, thus providing the resources to bridge the gap in human capital investment. According to the IMF investing tax revenues equivalent to 3% of GDP into infrastructure alone could lower the poverty rate by 24%. Splitting that public investment in education and infrastructure could reduce poverty even further. Education increases labour productivity and thus, income and long-run GDP.

Despite the significant contribution to the economy mining revenues currently account for only 2% of GDP. In 2022 authorities introduced set a formula for calculating the reference market price for bauxite and introduced it later in a budget law that forces mining firms to declare the sale price of the bauxite that they mine. At the recommendation of the IMF, the Government of Guinea is now considering establishing a so-called ‘stabilisation fund’, which would buffer mining investments from price fluctuations. While the law forbids unilateral change of the terms in the contract, the government can still conduct audit of tax exemptions to ascertain that mining companies have respected their contractual obligations, assess whether the reasons underlying the granting of tax exemptions are still valid, and ensure that tax exemptions are not automatically renewed at their expiration. The IMF has also recommended that authorities refrain from granting tax exemptions outside the mining code.

The second challenge is economic diversification (Cust and Zeufack, 2023). According to the University of Harvard’s Economic Complexity Index Guinea has the second ‘least complex economy’ in the world on account of its reliance for over 95% of its exports on basic mineral commodities. The only one of the 133 countries assessed with a lower score is Liberia.

In its conventions with mining companies there has been a strong focus on local content and on value addition through refining and in the case of Simandou - a requirement to progress towards the construction of a domestic steel mill.

The additional opportunity for economic diversification that Simandou offers and that differentiates it even further from current mining projects is the +600kms dual-use shared rail and port infrastructure. A similar mine-to-port infrastructure built by Vale, the second largest iron producer in the world, in Brazil shows that the shared use of its 230 million tonne rail line benefited mostly agriculture with 9 million tonnes of produce and fertilizer carried in 2019 (Brauch et al, 2020).

Agriculture exports (US$227m) have been falling since the start of the mining boom, and in 2021 it stood 23% below its peak in 2016 (US$294m), likely as a result of a loss of competitiveness due to what is commonly termed as the Dutch Disease.

If the average agricultural output of Guinea over its six million cultivated hectares - US$370 per hectare (2020) were to match Cote d’Ivoire’s (US$1020) the boost to the GDP would be almost US$4bn annually (FAO, 2024). The experience of Indonesia has shown the agricultural sector can step in to supplement extractive export revenues when they fall, as happened when Indonesia’s oil production fell from one million barrels per day in 2010 to just 638,000 in 2023 (Energy Institute, 2024).

Collaboration between Guinea and South-East Asia

Just as policy decisions, investment, and demand from South-East Asia and China have driven the mining boom the evidence above shows there is potential for economic collaboration with the region to contribute to improved outcomes for Guineans. There are existing initiatives for education, attracting non-mining investment and economic governance that could be expanded to deliver this goal and ensure Guinea escapes the resource curse.

In terms of education, there are already strong links between the governments of Guinea and Malaysia, with tens of scholarships to study in Higher Education institutions awarded every year. There have also been historically strong links in agricultural science between the Institut Superieur d’Agronomie in Guinea and Chinese universities. More recently, Winning helped establish an Institute of Rail Studies at the University of Conakry in collaboration with the University of Hunan in China (UGANC, 2023).

As far as potential for economic diversification goes, there is an opportunity to use the biennial Africa Singapore Business Forum (ASBF) to showcase the investment potential of Guinea, particularly in relation to the new Simandou rail and port corridor. Corporations already involved in supporting the ASBF, such as agricultural commodity trader Olam, food-to-infrastructure conglomerate Tolaram Group, and fertilizer producer Indorama could all be strategic investors for Guinea to attract.

In terms of strengthening economic governance, Winning Group has already identified an opportunity with the now long-running Sun scholarships to provide training for Guinean public officials at the renowned Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore (Winning, 2024).

On governance and policy dialogue in the resources space more specifically, there is an opportunity to build on recent discussions between ASEAN and the African Union’s African Mineral Development Centre (AMDC). African Union members have agreed that the AMDC will be headquartered in Conakry, and the Minister of Mines Bouna Sylla has made achieving this one of his top ten priorities (GuineeNews, 2024).

Finally, there is scope for collaboration between existing higher education institutions and thinktanks on specific research and policy analysis questions and capabilities. The NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies could play a role in this space as the only thinktank in South-East Asia that looks at Africa from a trade and business perspective.

(The author was a lead economist for the Simandou project at Rio Tinto)

*additional inputs by Amit Jain, Director NTU-SBF Centre for African Studies

References

Brauch, M.D. et al (2020), Shared-Use Infrastructure Along the World’s Largest Iron Ore Operation: Lessons Learned from the Carajás Corridor, Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment.

Campbell, B. (2010), “Guinea and Bauxite-Aluminium: The Challenge of Development and Poverty Reduction”, in Campbell, B., ed, (2009) Mining in Africa: Regulation and Development, International Development Research Centre.

CRU (2023), Bauxite and Alumina Long Term Market Outlook.

Cust and Zeufack (2023), Africa’s Resource Future: Harnessing Natural Resources for Economic Transformation during the Low-Carbon Transition, World Bank.

EITI (2024), https://eiti.org/countries, accessed 02/07/2024.

Energy Institute (2024), Statistical Review of World Energy.

FAO (2024), https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home, accessed 02/07/2024.

S&P Global (2024), Global Trade Atlas.

IMF Staff Reports Apr/May 2024

GuineeNews (2024), Mines : l’agenda du ministre Bouna Sylla en 10 points.

Harvard Growth Lab (2024), The Atlas of Economic Complexity, https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/.

IMF (2023), 2022 Article IV Consultation and Request for Disbursement Under the Rapid Credit Facility – Staff Report.

IMF (2024), 2024 Article IV Consultation and Request for Disbursement Under the Rapid Credit Facility – Staff Report.

Ministry of Mines and Geology of the Republic of Guinea (2018), Bulletin Statistiques Minieres No. 1.

Ministry of Mines and Geology of the Republic of Guinea (2024), Bulletin Statistiques Minieres et Carriers No. 22.

NRGI (2021), https://resourcegovernanceindex.org/, accessed 02/07/2024.

OECD (2023), Data Explorer: Aid (ODA) disbursements to countries and regions [DAC2A].

Rio Tinto (2023), Investor Seminar Sydney: 6 December 2023.

Transparency International (2023), https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023, accessed 02/07/2024.

UGANC (2023), Orientation des bacheliers: pourquoi choisir l’institut des chemins de fer de l’UGANC ?

UNDP (2024), Human Development Report 2023-24, Breaking the gridlock: Reimagining cooperation in a polarized world.

Winning (2024), Sun’s Scholarship: Building Friendship between Singapore and Guinea.

World Steel Association (2024), Annual Steel Data.

World Bank (2024), World Development Indicators.

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)