Samurais on a safari

Japanese influence is proving to a catalyst for broad-based growth and development in Africa

By Ronak Gopaldas

Introduction

In recent years there has been a downtick in Japanese investment into Africa. After peaking at US$24bn in 2013, capital flows to Africa dipped to a low of US$310m in 2021. This is despite sizeable investment pledges in 2013 and 2016 by former prime minister Shinzo Abe. At the 5th and 6th Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) gatherings, Abe committed a collective US$60bn for African states would have positioned Japan as Africa’s largest investment partner.[1]

Apparent lack of delivery has raised concern that Japan risks ceding initiative to historic rivals in China and ambitious emerging players like the United Arab Emirates. Indeed, the Emirates have stunned with a US$35bn pledge to Egypt this February.[2] Not only has it rescued Cairo from its economic malaise, but it is a clear statement of intent by the Emirates and its bid to consolidate its influence on the continent.

China, meanwhile, has continued to extend its control over critical minerals supply chains in Southern and Central Africa. China’s Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Company (CNMC) committed to US$1.3bn in capital to Zambia’s Chambishi and Luanshya copper mines after outbidding European rivals for the lucrative mines.[3] This is alongside a US$1bn plan to refurbish the Tanzania-Zambia railway to facilitate the transfer of the minerals.

Japanese sectors of influence

Japanese sectors of influence

In many ways Japan is present, although its contribution has largely gone between the headlines. This, in part, reflects the complexity of Japan’s engagement in Africa, and the delicate interplay between its ambitions and apprehension.

For one, the intent is there. This much is reflected by Japan’s investment commitments over the last decade. At US$90bn in the last decade, it is just short of China which has pledged in excess of US$100bn for Africa.[4] Although much of Japan’s planned investments are yet to materialise, the commitments themselves demonstrate the centrality of the continent to Tokyo’s strategic considerations. A salient piece of evidence is the fact that Japan is the fourth largest shareholder in the African Development Bank (AfDB) behind Nigeria, the United States, and the United Kingdom, having injected more than US$40bn in capital.[5] This places Tokyo at the top of policymaking and strategic investment on the continent.

At the sharp end of the official Japanese development aid Katana is the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which has spearheaded some groundbreaking ventures in Africa. In April 2023, JICA approved US$4bn for the Enhanced Private Sector Assistance (EPSA) initiative. A sizeable portion of this will go towards supporting private sector operations, especially start-ups with innovative solutions to financial inclusion, healthcare, and climate change related challenges.[6]

This further entrench Japan in Africa’s private sector, where it is already well represented. There are more than 400 Japanese companies on the continent according to the African Development Bank (AfDB).[7] This is the most by a single country after the United States, United Kingdom, China, and Germany. Many such companies have considerable scale and scope especially in the automotives, extractives, household technologies and heavy industry.

Toyota is the standout Japanese investor on the continent Africa. The Japanese automaker accounts for at least 15% of African vehicle market, employing more than 22,000 people. It also has presence in all 54 countries across the continent placing it in an exclusive club of international companies that have such geographic reach.[8] South Africa has been the foremost beneficiary of Toyota’s investment largesse. Between 2019 and 2021 it invested US$231.4m (ZAR 4.3bn). A portion of money went towards expanding its existing facility Durban to facilitate the production of the Corolla Cross hybrid vehicle – the first electric vehicle to be manufactured in Africa. In October that year, the first vehicles rolled off the line at Toyota’s Durban manufacturing plant.[9]

Japanese car manufacturers have also been at the forefront of Africa’s e-hailing revolution. Partnerships between Toyota, Suzuki and, Honda with companies such as Uber, Bolt, Chap Chap, and Moove, have facilitated the rapid spread of e-hailing services across the continent, which have become a vital element of the transport sector and employer of semi-skilled labour. In South Africa, Japanese vehicle makes – Toyota, Suzuki, Honda – comprise the bulk of the e-hailing fleet. Japan’s role in promoting access to mobility in Africa is understated when considering the concentration of used Japanese cars on the roads. Japan is the largest supplier of used vehicles and vehicles parts for Africa, with more than 300,000 imported by the continent in 2021.[10]

Japanese corporations are also decisive players in Africa’s most exciting gas prospect - Mozambique. Mitsui is the second largest shareholder in the so-called Mozambique LNG project, led by TotalEnergies and holds a 20% stake in the project – second only to the French energy giant that has a 26.5% majority.[11] With a final investment decision (FID) of US$20bn, the project remains Africa’s largest foreign direct investment in a single project. Much of this – US$14bn– has been provided by Japan’s MUFG Bank, Mizuho Bank, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking and Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank JBIC – making Mozambique the largest single recipient of Japanese investment in Africa. Japanese interests – Jera, Tokyo Gas and Tohoku Power - also account for 30% of purchase orders from the 12 million ton per annum project which promises to fast track Mozambique’s development by at least a generation. In making such a bullish move in Mozambique’s LNG sector, Japanese interest in the upstream gas projects in Africa is driven by the logic of its own energy security. Tokyo needs to diversify its long-term sources, as uncertainty looms of imports from Russia. Japan imported 66.2 million tonnes of gas in 2023, of which 6.13 million came from Russia. Although currently beset by its own shortcomings, gas from Mozambique can reasonably plug any gap that emerges as a result of market disruptions.

Emerging areas of interest

Japanese engagement in Mozambique LNG has paved way for other ventures into the lucrative Southern African market. In December, Sumitomo was part of a consortium with Electricite de France, that wa contracted to finance, construct and operate the US$5bn, 1,500MW dam, which is a cornerstone of Mozambique’s green energy transition.[12]

Sumitomo’s investment in Mpanda Nkuwa is indicative of Japanese interest in exploiting the green energy potential of Africa. Indeed, Japan has unveiled an official ‘green strategy’ for Africa. Dubbed the Green Growth Initiative for Africa, the plan is undergirded by a US$4bn fund, aimed at climate change mitigation and adaptation through private and public partnerships.[13]

Given its status as the leading hydrogen patent holder by country, Japanese interest in green energy has naturally gravitated towards the increasingly popular gaseous substance. Namibia – which is emerging as a hub for green hydrogen – has been among the largest beneficiaries of Japanese green investments. Sumitomo has partnered with Namibia’s energy parastatal, NamPower, to develop the Southern African country’s green hydrogen value chain. Meanwhile, Japan’s Mizuho Bank has paired with the Namibian Investment Promotion and Development Board for the establishment of a so-called green hydrogen hub. Elsewhere, Japan’s LEAD initiative is financing on and offshore windfarms in Egypt.[14]

Apprehensions and aversions

Despite natural synergies and areas in which Japanese companies have clear comparative advantage, Tokyo appears apprehensive. According to AfDB, Africa accounts for less than 0.005% of the whopping US$2trn foreign direct investment that Japan makes across the world.[15] The bulk of this – 70% – is concentrated in Southern Africa. Japan also accounts for merely 2% of Africa’s trade, and an even lesser share of African debt.[16]

The apparent aversion is seemingly rooted in a number of factors, including Japan’s own psyche, adaptive constraints and that norms that it applies to external engagement, particularly in Africa.

First there is Japanese custom, which serves as an underlying check on Japan’s publicity. Permeating Japanese personal and political engagement is the notion of “Kenkyo” which advocates for modesty and humility. Consequently, despite significant engagements across multiple domains in Africa, Japan finds difficulty in extolling its accomplishments.

Japanese ventures in Africa have also been tempered by a small diaspora in Africa. Unlike China and India which have had large populations for several generations living and working and across Africa, the Japanese are scarcely to be found. There are less than Japanese people in South Africa according to the latest census data, making them one of the smallest Asian diasporas.[17] This is in contrast to more than 350,000 people of Chinese descent and more than 1.6 million of Indian descent.

This is a strategic disadvantage. As argued by Seema Sangita, diasporic networks are integral to bridging information asymmetries, which are often at the root of apprehension among external investors.[18] They also assist in marrying cultural differences, establishing networks, and softening the adaptive process for new business. China and India have proven adept at leveraging these networks to their advantage. Japanese investors have few such trusted local networks to help navigate.

A new page

Japanese engagement in Africa is evolving. This is driven by several consideration, of which the first is recognition of its own strategic disadvantages. Japan faces a demographic decline, which poses a threat to its long-term economic stability .[19] The country’s population is forecast to halve from the current 125 million people by 2100, with cascading effects on its pool of human capital, tax base and productivity. As a result, it may be prudent to outsource some productive functions to low-cost markets in Africa. Population decline has also prompted Japan Inc. to seek fast growing markets in Africa and Asia to augment declining endogenous consumer demand; Africa with its rapidly expanding and spendthrift middle class has been a prime candidate.

Second, Japan’s dependence on the repurchase of resources from markets like China is a threat to its productivity and economic sovereignty, as evidenced by the 2010 Chinese ban on critical mineral exports.[20] To circumnavigate this, Japan has sought to raise its stakes in extractive projects across Africa, led by big ticket private investments such as Mitsui’s engagement in Mozambique’s LNG sector.

Third there appears to be a paradigm shift within Japanese spheres of influence over the country’s dovish approach to relations in Africa. As Emi Yasukawa writes for the Atlantic Council, Japanese leaders are increasingly questioning the efficacy of their approach to the continent. There is a growing school of thought in Tokyo that failure to embrace an element of pragmatism will continue to place the country at a disadvantage to China, which has less scruples when it comes to international engagements and is therefore able to extract greater benefits. The same of school of thought also advocates for Japan to be more assertive in rivalling China for strategic partnerships in Africa.[21]

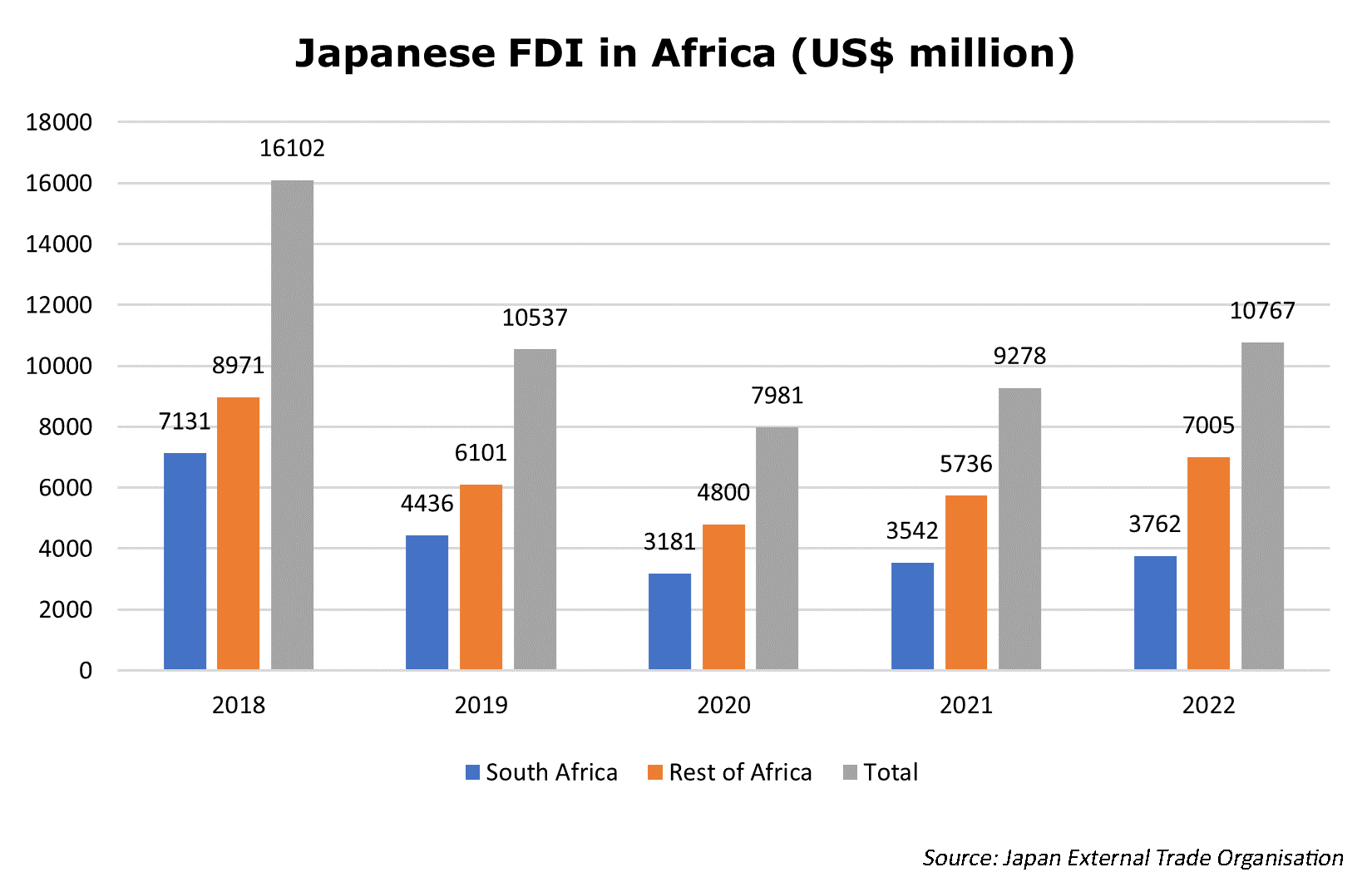

These considerations undergirded Japan’s most ambitious step in its relations with Africa yet – the US$30bn commitment made at the 2022 Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) in Tunisia. The sum marks a US$10bn increase from the pledge made at the prior TICAD. It will also see Japan’s net foreign direct investment (FDI) into the continent rebound to pre-coronavirus levels, where it amounted to more than US$10bn per year, from a low of US$5bn in 2020 and 2021.[22]

Japan has also ratcheted up its diplomatic charm offensive. TICAD was followed by a four-country tour of Africa by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida - the first such diplomatic engagement by a Japanese leader. Particularly noteworthy was Kishida’s rhetoric during the tour, where he bemoaned a ‘lost decade’ of Afro-Japanese engagement while alluding to Japanese ambitions to challenge China’s dominance on the continent. During these visits Kishida also endorsed African Union’s inclusion in the G20 and called for a permanent African seat in the United Nations Security Council – a position that Japan is also seeking. The African Union would eventually get admitted into the G20 in September 2023.[23]

Teaming up

To mitigate some of the risk and consternation associated with its African venture, Japan has forged strategic partnerships with countries that bare similar interest in Africa but have greater knowhow in navigating the prevailing complexities.

In 2017 Japan partnered with India in launched the so-called Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) to rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). According to the vision document, the two would collaborate to develop quality infrastructure, digital and institutional connectivity, economic capacity, and human capital among 17 member states.[24] Unlike the BRI which is almost entirely land-based, AAGC member states would be linked by a sea corridor, with smaller land anodes to landlocked countries such as Zambia and Zimbabwe. The initiative has been slow off the mark, with progress largely disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic and a pivot towards the Indo-Pacific region. It appears now the AAGC will be subsumed within this initiative.[25]

Japan has also forged an alliance with Turkey, which has emerged as a key powerbroker under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. This is particularly the case in opportune yet risky frontier markets in North and East Africa, where Turkey has leveraged defence cooperation as a basis for wider engagement. In 2019, the ad-hoc Turkey-Japan Partnership for Africa was established. This was with a view of promoting joint projects in trade, capacity building, skill development, health, infrastructure, energy, and connectivity.

Finally, in September Japan and the United Kingdom (UK) agreed to form a partnership to invest in critical minerals in Africa. This as part of a wider initiative to secure supply chains for strategic goods such as semiconductors and storage batteries, and break China’s dominance. Together, the UK and Japan would seek mining and refining sites for joint investment in Africa, leveraging the UK’s extensive knowledge and network on the continent.[26] In this regard, there was talk that Japan would augment the UK’s US$3bn investment pledge in Zambia, which – alongside the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – has emerged at the centre of global competition for critical minerals.

The Samurai’s touch

African attitudes towards Japan are also warming. Through investment commitments, partnerships with the AfDB and in endorsing African agenda at multinational platforms Japan and its leading corporations have begun to win hearts and minds on the continent.

African leaders have also begun to appreciate the low risk and sustainable nature of Japanese engagement, particularly as China’s begins to tighten purse strings. Kenya – whose largest creditor is China – has extended an invitation to Japan to support its infrastructure and industrialisation ambitions by leveraging public-private partnerships.[27]

Kenyan President William Ruto managed to secure US$2bn in deals, during his visit to Tokyo in Feb 2024, including an agreement with Toyota for the advancement of renewable energy projects. Meanwhile talks are ongoing on the establishment of a Toyota car manufacturing plant in East Africa’s most developed market. Kenya plans to raise US$500m through a bond sale in Japan in June 2024. It has US$3.5bn of foreign currency debt maturing this year and it is desperate to find new sources of finance. Kenyan finance minister Njuguna Ndung’u has stated that Nairobi could look at borrowing more from Japan.

Equally alluring for African policymakers is the reduced political risk of Japanese investment. Questionable adherence to local content requirements by its companies has made Chinese engagement less popular among electorates across the continent. Although contentious this is partly reflected by a slow decline of China’s popularity across Africa and the success of politicians espousing such a narrative including William Ruto of Kenya, Felix Tshisekedi of the DRC, and Hakainde Hichilema of Zambia. A 2020 survey by Afrobarometer found a drop in positive perceptions of Chinese influence in 10 out of 16 countries surveyed. Popular attitude towards China, however, continue to remain positive overall. On aggregate, 60% respondents in the survey stated that Chinese influence was “somewhat” or “very” positive. In 2015 that same opinion was 65%.[28]

Japanese engagement is favourably viewed in Africa as it is considered fair and prioritises job creation and human capital development. Despite being aligned with the Western geopolitical block Japan does not carry the same neo-colonial baggage that sometimes stigmatises Western investments in Africa. Perhaps, that is one reason why Africa is warming up to the Samurai’s touch.

Conclusion

Japan and Africa have synergistic advantages, which if exploited can unlock substantial economic benefits for both parties. Africa is looking to industrialise and modernise, whilst meeting important financial and environmental goals. Countries like South Africa, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Zambia have also embarked on ambitious reform agenda, de-regulating key sectors and privatising various state-owned enterprises; as such they are in search of new partners. All the while, Africa is eager to break its dependency on the East and the West and leverage multilateralism to maximise economic gains.

This presents a lucrative prospect for Japan and its myriad interests. Japan’s army of industry leading corporations have the know-how to assist Africa in its developmental and industrial aspirations. They also have the capital to deploy in what is a risky yet rewarding African market. Through Africa, Japan can also meet its growing need for natural resources, a repository for capital seeking high yield and a domicile for existing and new supply chains. Japan recognises this and is no longer content with being an afterthought in Africa. Indeed, the Samurai’s safari has just begun.

References

[1] Pajon, C. (2022). Japan’s Africa policy: Back to basics in times of crisis, Frech Institute of International Relations. Available at: https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/publications-ifri/articles-ifri/japans-africa-policy-back-basics-times-crisis (Accessed: 28 April 2024)

[2] Magdy, M., Daoud, Z. and Gunn, M. (2024) Oil-rich Abu Dhabi’s $35 billion gamble on Egypt, Bloomberg.com. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-03-16/oil-rich-abu-dhabi-s-35-billion-gamble-on-egypt (Accessed: 18 March 2024).

[3] Staden, C. van (2023) $1.3 billion Chinese investment in Zambian copper sector as EU readies competing deal, The China-Global South Project. Available at: https://chinaglobalsouth.com/2023/09/28/1-3-billion-chinese-investment-in-zambian-copper-sector-as-eu-readies-competing-deal/ (Accessed: 28 March 2024).

[4] De Freitas, M. (2023). The impact of Chinese investment in Africa: neocolonialism or cooperation. Policy Centre for the New South. https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/2023-08/PB_30-23_Marcus%20Freitas.pdf. (Accessed: 27 April 2024)

[5] Fitch Ratings.(2023) African Development Bank Rating Report. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/african-development-bank-24-07-2023 (Accessed 30 April 2024_

[7]AFBD (2023) Investing in Africa is profitable, African Development Bank president ... Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/investing-africa-profitable-african-development-bank-president-tells-japanese-investors-60551 (Accessed: 22 March 2024).

[8] Africa: Toyota Tsusho (no date) Toyota Tsusho Corporation. Available at: https://www.toyota-tsusho.com/english/company/business/africa.html (Accessed: 26 March 2024).

[9] Maharaj, N. (2022) Toyota SA pours billions into the economy, ZAWYA. Available at: https://www.zawya.com/en/economy/toyota-sa-pours-billions-into-the-economy-ae18s9w2 (Accessed: 26 March 2024).

[10] Number of used car exports from Japan in 2021, by importing region. Available at: https://blog.japanesecartrade.com/334-africa-the-largest-market-for-japanese-used-vehicles/ (Accessed: 30 April 2024)

[11] Mitsui (2019) Mitsui & Co., ltd.. investor relations division, Final Investment Decision for the Mozambique LNG Project - MITSUI & CO., LTD. Available at: https://www.mitsui.com/jp/en/release/2019/1228889_11219.html (Accessed: 18 March 2024).

[12] Ingram, E. (2023) Consortium selected to develop 1.5 GW Mphanda NKUWA hydropower project in Mozambique, Hydro Review. Available at: https://www.hydroreview.com/hydro-industry-news/new-development/consortium-selected-to-develop-1-5-gw-mphanda-nkuwa-hydropower-project-in-mozambique/#gref (Accessed: 17 April 2024).

[13] Yasukawa, E (2023) Green investment takes the lead: Japan’s revamped approach in Africa, Atlantic Council. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/green-investment-takes-the-lead-japans-revamped-approach-in-africa/ (Accessed: 02 March 2024).

[14] Matthys, D. (2023) Japan enters Namibia’s Green Hydrogen Rush, The Namibian. Available at: https://www.namibian.com.na/japan-enters-namibias-green-hydrogen-rush/ (Accessed: 20 March 2024).

[15] AFBD (no date) Investing in Africa is profitable, African Development Bank president. African Development Bank Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/investing-africa-profitable-african-development-bank-president-tells-japanese-investors-60551 (Accessed: 22 March 2024).

[16] Japanese investors say they want more business with Africa, African Development Bank. Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/japanese-investors-say-they-want-more-business-africa-60968 (Accessed: 19 March 2024).

[17] Census 2002 (no date) Statssa.gov.za. Available at: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjw2a6wBhCVARIsABPeH1uuWLzDm86rTRzfPvm7sEHLi6V8S5YSAKmwqLLSGxmxayvo1Xw1pusaAqfAEALw_wcB (Accessed: 02 March 2024).

[18] Sangita, S. (2013) The effect of Diasporic Business Networks on International Trade Flows. Review of International Economics, Wiley Blackwell. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/r/eee/ecolet/v104y2009i2p72-75.html. (Accessed: 13 March 2024).

[19] Japan’s Demographic Challenge < Sasakawa USA (2017) Sasakawa USA. Available at: https://spfusa.org/publications/japans-demographic-challenge/ (Accessed: 02 March 2024).

[20] Evenett, S. and Fritz, J. (2023) Revisiting the china–japan rare earths dispute of 2010, CEPR. Available at: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/revisiting-china-japan-rare-earths-dispute-2010 (Accessed: 24 March 2024).

[21] Yasukawa, E. (2023) Green investment takes the lead: Japan’s revamped approach in Africa, Atlantic Council. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/green-investment-takes-the-lead-japans-revamped-approach-in-africa/ (Accessed: 02 March 2024).

[22] TICAD 8 - Official website - News. (2022) Available at: https://www.ticad8.tn/post/44/japan-pm-announces-30-billion-in-funding-for-africa-over-next-three-years (Accessed: 01 April 2024).

[23] Reuters. (2023) Japan’s PM Kishida seeks closer ties with Africa in bid to woo ... Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/japans-pm-kishida-seeks-closer-ties-with-africa-bid-woo-global-south-2023-05-04/ (Accessed: 03 March 2024).

[24] The Asia–africa growth corridor: Bringing together Old Partnerships and new initiatives (2019) orfonline.org. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/research/modi-and-chogm-2018-reimagining-the-commonwealth-harsh-v-pantakshay-ranade#:~:text=The%20AAGC%20focuses%20on%20capacity,chains%20in%20Africa%20and%20Asia. (Accessed: 02 April 2024).

[25] Saaliq, S. and Yamaguchi, M. (2023) Japan PM Kishida announces New Indo-Pacific Plan in India, AP News. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/india-japan-modi-kishida-meeting-2ccec67ae7fa4b26090316d3d98a5b59 (Accessed: 02 April 2024).

[26] Nishino, A. (2023) Japan and U.K. launch economic security dialogue, Nikkei Asia. Available at: https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-and-U.K.-launch-economic-security-dialogue (Accessed: 01 April 2024).

[27] Anami, L. and Kitimo, A. (2024) Cautious on debt, Ruto Woos japan with public-private deals for projects, The East African. Available at: https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/cautious-on-debt-ruto-woos-japan-with-public-private-deals-for-projects-4520618 (Accessed: 01 March 2024).

[28] Sheehy, T. (2021). Countering China on the Continent: A Look at African Views, United States Institute of Peace. Available: https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/06/countering-china-continent-look-african (Accessed: 06 April 2024).

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)