Where is Africa in the cloud?

African data is stored on data centres outside the continent but that may be about to change

By Rafiq Raji

Introduction

Foreign investors are keen on the African cloud computing market, which currently has a penetration rate of about 15%, but is set to grow significantly.[1] An increasing number of undersea cables connecting the continent to high speed internet is enabling this growth.[2] African companies are increasingly moving to the cloud. But these are mostly run by foreign service providers whose data centres have been traditionally located overseas.[3] 70% of Nigerian government agencies host their data abroad.[4] Cost, reliability, and data storage size are often compelling reasons why some African firms and governments still prefer to host their data abroad.[5] These factors often trump concerns around data security and privacy. That is beginning to change. International cloud service providers now compete with local ones. Big Tech certainly senses an opportunity.[6] IBM, Microsoft, Amazon, and Oracle, which operate data centres in Africa, are building additional capacity.

In assessing the state of the African cloud computing market, I find that while it is indeed growing, with potential for even greater expansion, it will be constrained by still intractable infrastructural deficiencies on the continent and how as the cloud underpins the rising centralisation trend by global tech via software as a service (SaaS), African subscribers will remain firmly tethered to hardware domiciled abroad regardless.

Data centres, cloud computing & cloud services

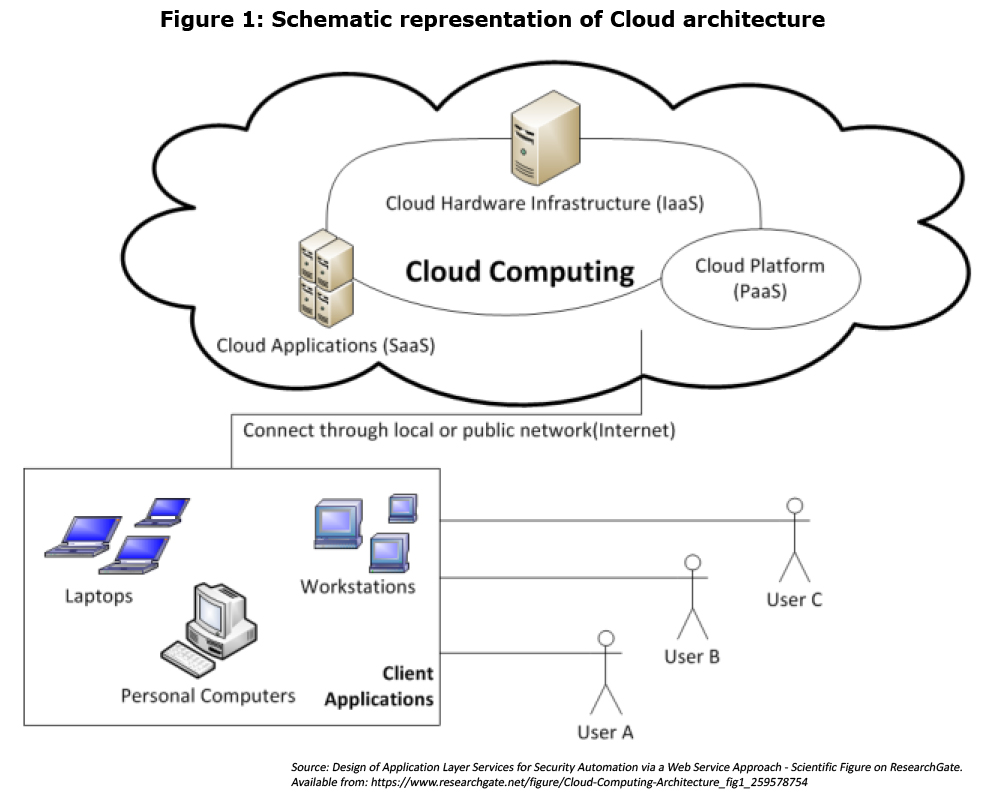

Put simply, cloud computing is the outsourcing of the information technology (IT) requirements of digital services to third-party providers, thus allowing firms and governments to concentrate on their core business. These IT requirements range from software applications, hardware infrastructure, to the internet platforms through which digital services are delivered to end-users. Still, ‘the Cloud’ has evolved into “a metaphor for the services provided over the internet.”[7] Thus, cloud computing refers to how varied hardware and software resources are pooled and managed to deliver services over the internet. As shown in Figure 1, these cloud services are mainly of three types viz. Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS).[8]

Data centres are the infrastructural backbone of cloud services, even as they are offered as a service - a so-called Data centre-as-a-Service (DaaS) - which is really just a type of IaaS (Dillon, Wu, & Chang, 2010). Still, the distinction has to be made between data centres and cloud computing, which has evolved to a gamut of IT services, with third-party data centres only just a part but key component of the cloud’s ecosystem.

Big Tech dominates the global cloud computing market

The global cloud infrastructure service revenue was about US$180bn in 2021, according to Statista, with Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud and Microsoft Azure - the so-called ‘hyperscalers’ – topping the list (see Table 1 and Figure 2).[9],[10] Cloud not only offers subscribers hardware but software as well. SaaS will hardly be optimal for customers without either IaaS or PaaS or both. Unsurprisingly, there are concerns about the growing dependence by firms on the cloud as it is dominated by just a few big tech firms. In the banking industry, for instance, the oligopolistic global cloud computing market is the perfect recipe for the ultimate archetypal centralisation - a source of concentration risk in an industry where the principle of risk management is designed to avoid precisely such an agglomeration. The Bank of International Settlements highlighted how the increasingly oligopolistic nature of the global cloud computing industry could have “systematic implications for the financial system” in a July 2022 report.

The global cloud computing industry is consolidating even further with big tech backward integrating to own data centres, in addition to the software production and online platforms they already dominate - thus creating an almost perfect end-to-end ecosystem that offers users everything from data storage and software to e-platforms. European authorities have been among the first to raise concerns about the dominance of a few American firms in the global cloud computing industry.[11],[12] Ironically, American authorities similarly worry about the growing dominance of Chinese tech firms in Africa, where, for instance, “a third of [state-backed] Huawei’s [global] cloud and e-government deals are concentrated.”[13]

The global cloud computing industry is consolidating even further with big tech backward integrating to own data centres, in addition to the software production and online platforms they already dominate - thus creating an almost perfect end-to-end ecosystem that offers users everything from data storage and software to e-platforms. European authorities have been among the first to raise concerns about the dominance of a few American firms in the global cloud computing industry.[11],[12] Ironically, American authorities similarly worry about the growing dominance of Chinese tech firms in Africa, where, for instance, “a third of [state-backed] Huawei’s [global] cloud and e-government deals are concentrated.”[13]

Globally, SMEs have been able to adapt to the cloud much more quickly than large firms, which remain stuck with costly legacy systems. According to the UK-based technology consultancy Omdia it takes longer, about five to ten years, for big firms to make the transition to cloud computing. It predicts that large firms will spend more on the cloud over the medium term to 2025.[16] New digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence, which require greater data storage and computing power than most firms would be able to afford or expend capital on optimally, is motivating cloud adoption beyond just cost reasons. Incidentally, the African case is uniquely receptive to cloud computing, as SMEs constitute about 90% of all firms and account for 80% of jobs.[17] Besides, the few big African firms do not suffer similar legacy constraints as their foreign counterparts, as their size has been contemporaneous with the evolution of the internet, and their need for a digital service proposition is a relatively recent one.

Africa’s cloud computing market is growing

According to the Africa Data Centres Association (ADCA) data hosting capacity on the African continent is doubled in size to 200 MW between 2016-19. Earlier concentrated mostly in South Africa, it is now relatively better spread across the continent.[18] In June 2021, Senegal commissioned a brand new national data centre which will store all of the official data . Built by the Chinese telecom giant Huawei, the data centre is connected by an undersea cable and 6,000km domestic fibre optic.[19] This move has not gone unnoticed. Advocates are calling for other African governments to follow suit.[20]

Scandinavian countries rank high on the list of places that host data centres. Ample renewable power and the freezing weather provides ideal conditions to set up stacks of heat-generating servers. Scandinavian countries also boast some of the fastest download and upload speeds in the world.[21] Even so, America remains by far the world’s largest cloud computing country with a market size of US$116bn, with China coming a distant second - at US$38bn (see Table 2).[22] South Africa, despite its floundering power infrastructure, remains the favourite destination for data centres. Microsoft Amazon, Google, Huawei, and most recently, Oracle, have built their data centres in South Africa, for instance (see Table 3).[23] South African data centre firms have shown themselves capable of competing with global big tech.[24]

Scandinavian countries rank high on the list of places that host data centres. Ample renewable power and the freezing weather provides ideal conditions to set up stacks of heat-generating servers. Scandinavian countries also boast some of the fastest download and upload speeds in the world.[21] Even so, America remains by far the world’s largest cloud computing country with a market size of US$116bn, with China coming a distant second - at US$38bn (see Table 2).[22] South Africa, despite its floundering power infrastructure, remains the favourite destination for data centres. Microsoft Amazon, Google, Huawei, and most recently, Oracle, have built their data centres in South Africa, for instance (see Table 3).[23] South African data centre firms have shown themselves capable of competing with global big tech.[24]

According to the 2021 State of Industry Report by the Africa Data Centres Association (ADCA), the US$2bn African data centre market is expected to become US$5bn by 2016. Teraco is building a US$220m 80MW DC in Johannesburg, South Africa, which is expected to come online in 2022. Africa Data Centres is projecting its total data capacity to grow to 54MW by 2025. Raxio Group has plans to set up data centres in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Other capacity boost plans are afoot. IX Africa Data Centre is constructing a 42.5MW DC in Nairobi, Kenya, for instance, so is Icolo with another 1.6MW data centre in Mombasa – adding to its existing network of two data centres of the same size. Wingu.africa is building the first hyperscale data centre in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, with another planned for Adama city. Other data centre investments in the pipeline are in Senegal (financed by Morocco’s N+ONE) and in Togo (financed by the World Bank), which will be the republic’s first carrier-neutral data centre.

According to the 2021 State of Industry Report by the Africa Data Centres Association (ADCA), the US$2bn African data centre market is expected to become US$5bn by 2016. Teraco is building a US$220m 80MW DC in Johannesburg, South Africa, which is expected to come online in 2022. Africa Data Centres is projecting its total data capacity to grow to 54MW by 2025. Raxio Group has plans to set up data centres in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Other capacity boost plans are afoot. IX Africa Data Centre is constructing a 42.5MW DC in Nairobi, Kenya, for instance, so is Icolo with another 1.6MW data centre in Mombasa – adding to its existing network of two data centres of the same size. Wingu.africa is building the first hyperscale data centre in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, with another planned for Adama city. Other data centre investments in the pipeline are in Senegal (financed by Morocco’s N+ONE) and in Togo (financed by the World Bank), which will be the republic’s first carrier-neutral data centre.

In September 2021, IBM secured cloud deals with some of Africa’s largest banks in Morocco, South Africa, Nigeria and Mozambique – evidence of the growing demand for the services.[26] A boom in the digital economy is boosting demand for online data storage by banks and mobile telecommunication firms.[27] Apart from cost advantages, cloud services also offer time efficiencies allowing firms to boost sales optimally. Data localisation requirements by African governments is also a major driver of demand. In the South African case, for instance, the authorities explicitly state in the draft national data and cloud policy that data generated on the country’s shores will be the property of South Africa.[28]

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is also expected to be an enabler of greater and easier cross-border data centre investments as current trade barriers like varied taxes limit investments to existing hubs, with South Africa often a preference owing to its relatively better infrastructure and opportunities for synergies due to an already high concentration of data centres in the country. But that is changing. Planned data centre investments in Nigeria, when completed, will put South Africa in second place over the immediate medium term of 2022-26, for instance. Regulation requiring compulsory onshore data domiciliation will also be a catalyst, as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) by the European Union has shown. At least 19 African countries had passed data protection laws in 2019, according to the ADCA, and they almost always insist on data onshoring.

Infrastructural constraints will weigh on data centre growth

Despite the increasing number of data centres being built on African countries 80% of the continent’s data continues to be stored offshore thus limiting the ability of African data centre operators to offer the fullest range of services. For this to change, the African continent will need more submarine internet cables of its own, compared to the current scenario where only a few pipes branch to the continent. A report by the Africa Data Centres Association and Xalam Analytics estimates that Africa needs anything between 1.4m to 3.5m square metres of data centre space to meet its requirements. The running of data centres is very power intensive. That presents a big hurdle in a continent that is struggling to bridge a large power deficit. Data centres, therefore, cannot depend on grid power. This means investing in power generation. Some data centre operators in Nigeria locate their facilities close to power transmission stations. But their distribution capacity, even when running fully, is so inadequate that they are only able to spare a few megawatts of electricity. In South Africa, Eskom, the state-run power utility, is almost bankrupt and blackouts have become commonplace. But now that regulations on private power generation has been relaxed data centres operators may soon be able to add new power generation capacity.[29]

African countries still have limited broadband internet coverage (see Table 4). Lingering legacy power infrastructure constraints, which are ordinarily limiting, sustain a vicious cycle that impedes the development of the foundations upon which faster internet infrastructure must be laid on. Some governments have shown enthusiasm toward 5G mobile telephony, which is seen as a means through which growth in cloud computing could be leveraged on, as it will enable quicker internet connections that can carry heavier loads of data at a time. Limited tech talent is also a constraint. With varied tech skill levels across the continent, seamless movement of people and capital that the AfCFTA is aimed at should ease current difficulties in due course. But this may also take a while, as even the hitherto easing intra-African travel restrictions were hardened again owing to the Covid-19 pandemic and may take longer still before they are eased again, and perhaps much more thereafter to the extent envisaged in the AfCFTA.

African countries still have limited broadband internet coverage (see Table 4). Lingering legacy power infrastructure constraints, which are ordinarily limiting, sustain a vicious cycle that impedes the development of the foundations upon which faster internet infrastructure must be laid on. Some governments have shown enthusiasm toward 5G mobile telephony, which is seen as a means through which growth in cloud computing could be leveraged on, as it will enable quicker internet connections that can carry heavier loads of data at a time. Limited tech talent is also a constraint. With varied tech skill levels across the continent, seamless movement of people and capital that the AfCFTA is aimed at should ease current difficulties in due course. But this may also take a while, as even the hitherto easing intra-African travel restrictions were hardened again owing to the Covid-19 pandemic and may take longer still before they are eased again, and perhaps much more thereafter to the extent envisaged in the AfCFTA.

When the myriad infrastructural challenges are countenanced, from power shortages, limited bandwidth, low broadband spread, and constraining regulations, it is easy to see to spot the dark clouds that will weigh on the prospect of the African data centre market outlook. The continent’s telecoms industry continues to boom despite the challenges of recent years, from Covid-19, the Russia-Ukraine War, rising inflation, depleting incomes, and growing indebtedness of African governments. Hitherto closed telecoms industry in African countries like Ethiopia that have begun to open up also point to growth potential. There is already growing recognition about the continent’s tech potential with venture capital funding on the rise. In 2021, US$4bn worth of venture financing was secured by various African tech startups spread across the continent, albeit concentrated in Nigeria, South Africa, and Kenya, with US$1.8bn in new VC funding already recorded in Q1 2022.[31]

Conclusion

While cloud computing is still a novelty of sorts for African firms and governments, there is an increasing trend of adoption, even though there is still a preference for foreign data storage providers. The arrival of cloud has certainly made massive investments on in-house data servers redundant. New submarine internet cables on the shores of the continent, with others planned, will enable faster and heavier data transmission. Basic infrastructure like electricity, which remains in short supply in many African countries, is a constraint, adding to costs. Electricity via diesel-powered generators in key markets like Nigeria, where almost the entire value chain, from the docking station of the internet submarine cables, the telecommunication masts that send the signals, to the banks and firms that offer digital services, depend on privately generated power is expensive and limiting. Unfortunately, this is a constraint that will endure in many African countries for a long while, as new power generation capacity is not being added fast enough to match the growth in internet infrastructure and the digital economy.

African governments, which still rely a great deal on foreign data centres, are increasingly pivoting towards localisation for public and private data. Sensing an opportunity, Chinese firms have been leading the charge, offering to build data centres for African governments that oblige, most recently in Senegal. There are concerns that the intentions of the Chinese in offering to engender data localisation are not anymore self-interested than those of their western counterparts. In any case, western tech firms have not been particularly enthused about data localisation, opting instead to build their own data centres on the continent, which are no more than extensions of their server farms abroad. Even so, a robust trend towards data localisation, with laws and infrastructure in tandem, suggests the outlook for cloud computing in Africa is very bright indeed. In sum, more carrier-neutral DC capacity will be required to service what is palpably a robust long-term African demand. A continental unification of standards, layered on the AfCFTA, say, will be a key prequisite to success. Some constraints will take a while to overcome. Energy and internet infrastructure will take a while to build as will the scarce African tech talent that will be required to run the data centres.

References

[1] Ritson, W. (2021, August 13). Africa finally has its head in the Cloud – but is it private, public or hybrid? Retrieved from https://www.liquid.tech/insights/innovation-blog/Africa_finally_has_its_head_in_the_Cloud_but_is_it_private_public_or_hybrid

[2] An interactive view of cloud computing in Africa (2021, January 25). International Finance. Retrieved from https://internationalfinance.com/an-interactive-view-of-cloud-computing-in-africa/

[3] Idris, A. (2020, May 29). Africa’s cloud computing industry is set to grow as data adoption rises. Tech Cabal. Retrieved from https://techcabal.com/2020/05/29/africas-cloud-computing-industry-is-set-to-grow-as-data-adoption-rises/

[4] Adepetun, A. (2021, June 4). 70% of govt agencies host data abroad despite $220m local infrastructure. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/technology/70-of-govt-agencies-host-data-abroad-despite-220m-local-infrastructure/

[5] Velluet, Q. (2021, July 26). Cloud technology in Africa: who is doing what, where? Teraco, Raxio, Rack Centre. The Africa Report. Retrieved from https://www.theafricareport.com/111593/cloud-technology-in-africa-who-is-doing-what-where-teraco-raxio-rack-centre/

[6] Data centres are taking root in Africa (2021, December 4). The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2021/12/04/data-centres-are-taking-root-in-africa

[7] Surbiryala, J. & Rong, C. (2019). Cloud Computing: History and Overview. 2019 IEEE Cloud Summit, 2019, pp. 1-7. Retrieved from https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9045506

[8] Dillon, T., Wu, C. & Chang, E. (2010). Cloud Computing: Issues and Challenges. 2010 24th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, pp. 27-33. Retrieved from https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5474674

[9] Agnew, H. (2022, June 29). Hedge fund manager Jim Chanos’s next ‘big short’ is data centres. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/e89e7071-0f1d-4bea-a857-a6fce236d776

[10] Richter, F. (2022, February 8). Amazon leads $180-Billion Cloud Market. Statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/chart/18819/worldwide-market-share-of-leading-cloud-infrastructure-service-providers/

[11] Waters, R. (2022, May 19). Microsoft woos Brussels as battle over the cloud intensifies. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/8caa142c-8db4-44c9-a582-d327eb1b29f8

[12] Nextcloud (2021, November 29). EU coalition urges EU to push back against gate keeping by Microsoft, files official complaint [Press release]. Retrieved from https://antitrust.nextcloud.com/press-release.pdf

[13] Hillman, J.E. & McCalpin, M. (2021, May 17). Huawei’s global cloud strategy. Washington DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from https://reconasia.csis.org/huawei-global-cloud-strategy/

[14] Crisanto, J.C., Ehrentraud, J., Fabian, M. & Monteil, A. (2022). Big tech interdependencies – a key policy blind spot. Basel, Switzerland: Bank of International Settlements. Retrieved from https://www.bis.org/fsi/publ/insights44.pdf

[15] Steer, G. (2022, July 6). Finance’s big tech problem. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/41f400b6-f83f-4fa1-8dac-731acddcf8f2

[16] Fildes, N. (2021, December 1). Digital demand sets cloud computing on course for next stage. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/5e0774a5-4a04-4b12-a8e0-09891bae7a09

[17] Runde, D.F., Savoy, C.M. & Staguhn, J. (2021, July 7). Supporting small and medium enterprises in sub-Saharan Africa through blended finance. Washington DC: Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/analysis/supporting-small-and-medium-enterprises-sub-saharan-africa-through-blended-finance

[18] Africa Data Centres Association (2021). State of the African Data Centre Market 2021. Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire: Africa Data Centres Association. Retrieved from http://africadca.org/en/state-of-african-data-centre-market-2021

[19] Senegal aims for digital sovereignty with new China-backed data centre (2021, June 22). Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/senegal-datacenter-idINL5N2O44D3

[20] Anuforo, C. (2022, March 16). Africa Data Centres calls for in-country hosting of cloud services. The Sun. Retrieved from https://www.sunnewsonline.com/africa-data-centres-calls-for-in-country-hosting-of-cloud-services/

[21] Barklie, G. & Patton, C. (2020, December 2). Where’s the best country to put a data centre? Investment Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/analysis/wheres-the-best-country-to-put-a-data-centre

[22] Williams, L. (2022, January 19). Is the US’s position as a global leader for data centres unassailable? Investment Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/tech/data-centres-activity-us-investment

[23] Mukherjee, S. & Mukherjee, P. (2022, January 19). Oracle opens data centre to provide cloud services across Africa. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/technology/oracle-opens-data-centre-provide-cloud-services-across-africa-2022-01-19/

[24] Gillwald, A., Moyo, M., Adam, L., Odufuywa, F., Frempong, G. & Kamoun, F. (2014). The cloud over Africa. Cape Town: Research ICT Africa. Retrieved from https://www.researchictafrica.net/publications/Evidence_for_ICT_Policy_Action/Policy_Paper_20_-_The_cloud_over_Africa.pdf

[25] Console Connect (2020). Africa Interconnection Report: Analysis of Sub-Saharan Africa’s Cloud & Data Centre Ecosystem. Queensland, Australia: Console Connect. Retrieved at https://f.hubspotusercontent00.net/hubfs/3076203/Africa%20Interconnection%20Report%202021.pdf

[26] Prinsloo, L. (2021, September 22). IBM Wins Africa Cloud Deals as Banks Quicken Switch to Digital. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-09-22/ibm-wins-africa-cloud-deals-as-banks-quicken-switch-to-digital

[27] Ferranti, M. (2021, March 10). New Raxio data centres signal demand for SasS, cloud tech in sub-Sahara. CIO. Retrieved from https://www.cio.com/article/191446/raxios-new-drc-data-centre-expands-regional-hosting-cloud-options.html

[28] Schneidman, W., Cooper, D., Govender, D., Mkhize, M. & Naidoo, S. (2021, November 4). Overview of South Africa’s Draft National Data and Cloud Policy. Retrieved from https://www.covafrica.com/2021/11/overview-of-south-africas-draft-national-data-and-cloud-policy/

[29] Burkhardt, P. & Sguazzin, A. (2022, July 25). S.Africa unshackles private sector in bid to end blackouts. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/south-africa-removes-license-rules-for-private-power-generators-1.1796749

[30] International Telecommunication Union (2021). Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2021. Geneva: ITU. Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/FactsFigures2021.pdf

[31] Siele, M. (2022, June 9). Why Africa is defying global trends in VC funding. Quartz. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/2175765/the-big-deal-vc-funding-in-africa-is-up-150-percent-from-q1-2021-to-q1-2022/

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)