Why is the Kenyan youth up in arms against new taxes

Understanding the factors fueling the backlash against the finance bill

By Franklin Obeng-Odoom

Abstract

Protesting taxes is common in Africa. So is evading taxes. Both are acts of resistance to top-down colonial ‘rent theft’ - often informed by IMF and World Bank advice but rarely based on consulting common people. In this context, the Kenyan youth protesting newer and higher taxes are right. Such taxes are wrong. But the question of financing Kenya’s development remains unaddressed. The proposed alternative – austerity, efficiency, and transparency – is insidious. In this dilemma of what else to do, ‘it may be asked’, as Nicholas Kaldor once noted on the pages of the Journal of Modern African Studies, ‘What are the most appropriate taxes that can be relied on for maximum revenue?’ (Kaldor, 1963, p. 8). To address this question the focus could shift away from state capacity, corruption and poor leadership to the existential social problems of inequality and social stratification instead. Emphasis must be put on the increasing wealth gap within Kenya and the asymmetry of power between Kenya and its foreign lenders. Such a framework would justify reducing taxes on labour, socialising the private appropriation of socially created rent, and demanding reparations for rent theft.

Finance Bill 2024

The Government of Kenya has withdrawn the Finance Bill. Protests erupted in June 2024 after the government of President William Ruto introduced a bill in the parliament that was projected to raise up to US$2.7bn in revenues. The Kenyan youth were right to protest the IMF-World Bank-inspired proposal to increase taxes. Unlike previous political anti-government protests, the challenge to the Finance Bill was a spontaneous self-directed reaction by Kenya’s Gen-Z who feel increasingly squeezed by the rising cost of living and lack of job opportunities. The anger of the youth forced President Ruto to back down and withdraw some of the most contentious provisions of the finance bill, including a proposed 16% value-added tax (VAT) on bread and 25% duty on cooking oil. The Finance Bill also sought to bring App-based services such as ride-hailing taxis; food delivery; and freelance professional services under the purview of income tax.

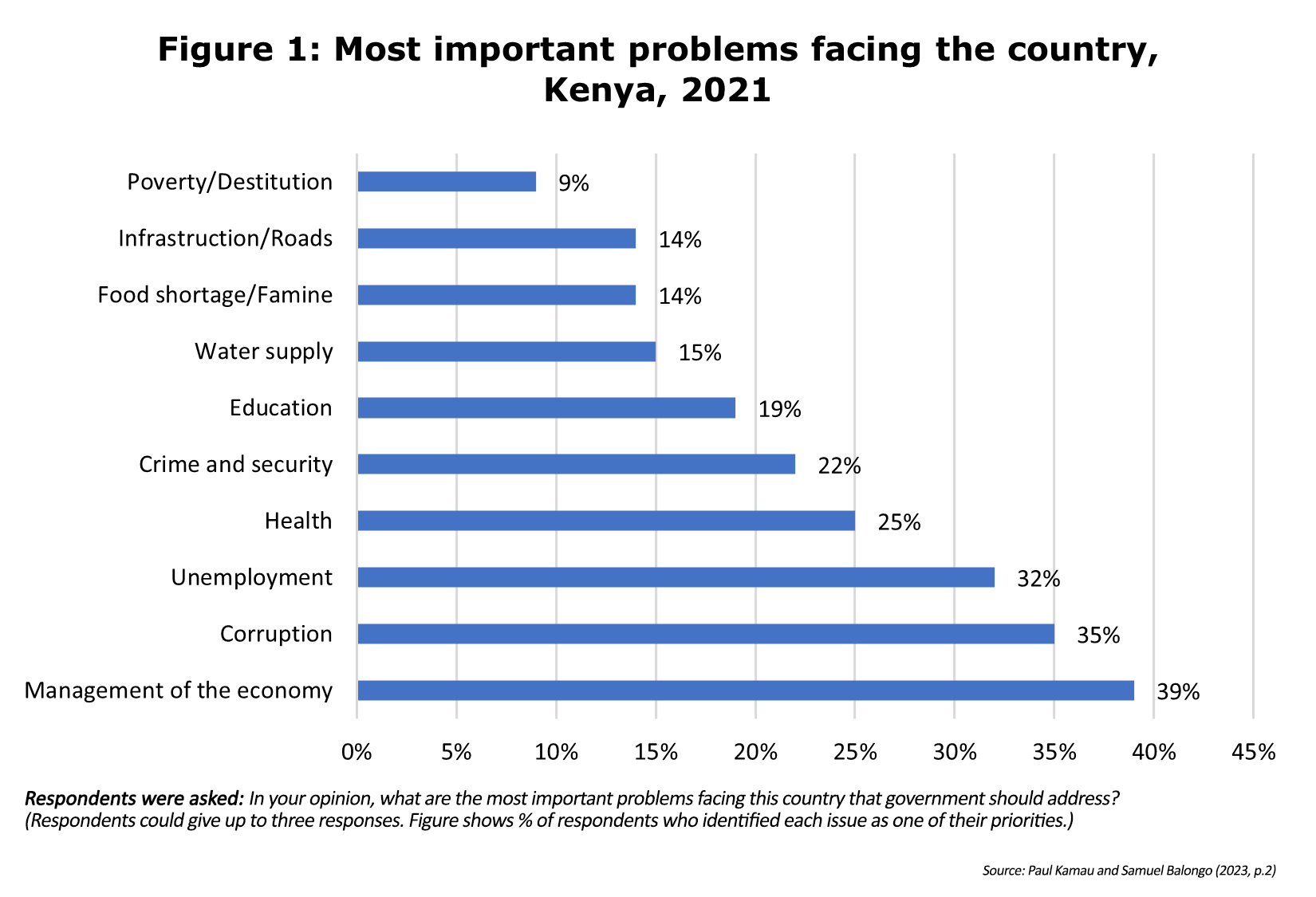

That would have made life much harder for a society already struggling with rising cost of living. Surveys show that 8.7 % of urban households in Kenya are multidimensionally deprived in 33.3 % of the selected dimensional indicators of well-being. Also, these surveys show that over 50 % of urban households are deprived of drinking water and sanitation services’ (Maket, 2024, p. 1). So, when the 2021 Afrobarometer survey asked respondents what the most important problems of the country were, ‘managing the economy’ came first (Fig 1) followed by corruption.

Unemployment came third. Health, crime, and education were considered important too. Many of these issues have been raised by Kenyan economists for years. Fredrick Masinde Wamalwa and his colleagues (e.g., Wamalwa, 2009; Wamalwa and Burns, 2018), for example, show the persistence of that education, youth, and unemployment problems in Kenya within the wider context of inequality and growth. Recent evidence seems to support the contention that there are more pressing issues than poverty. Figure 1 shows only 9% of those polled considered poverty as an issue.

Unemployment came third. Health, crime, and education were considered important too. Many of these issues have been raised by Kenyan economists for years. Fredrick Masinde Wamalwa and his colleagues (e.g., Wamalwa, 2009; Wamalwa and Burns, 2018), for example, show the persistence of that education, youth, and unemployment problems in Kenya within the wider context of inequality and growth. Recent evidence seems to support the contention that there are more pressing issues than poverty. Figure 1 shows only 9% of those polled considered poverty as an issue.

But there are dark clouds of inequality hanging over the data. Wamalwa and Burns (2018) show that inequality in education is a more serious problem in Kenya. Urban residents were, for the most part, also more concerned on many of these issues. This is probably because inequality is a more visible problem in Kenya. The Ghanaian capital Accra is one of the most unequal cities in Africa, but when compared with Nairobi, the latter was seen to be more divided. Urban slum population growth in Ghana was negative, but it was positive in Kenya (Otiso and Owusu, 2008). GDP per capita in Ghana was higher and, while education indices are higher in Kenya, the environmental crises in Kenya seem particularly dire. ‘Over 24 million plastic bags are consumed in Kenya monthly. Plastic bags now constitute the biggest challenge to solid waste management in Nairobi’ (Njeru, 2006, p. 1047). But this waste problem is concentrated in poorer areas. The rich are barricaded from the filth. The image of Nairobi is the brighter side of the wealth divide. Indeed, ‘higher poverty incidence, intensity, and urban multidimensional poverty exist among female-headed households, old household headships, and households residing in peri-urban regions’ (Maket, 2024, p.1).

‘Looking at age groups’, wrote Paul Kamau and Samuel Balongo (2023, p.6) ‘the youth (aged 18-35) appeared to be more concerned than their elders about corruption, unemployment, and crime/security’. On the other hand, middle-aged older citizens were more likely than the youth to cite health and food shortages. In such conditions, piling more taxes can only make a bad situation worse. Those who work for the government are perceived to be doing so much better. That is what rankled the youth forcing them to take to the streets. Clearly, then, their anger is justified. But urban economic decay did not start today.

Decades of (Urban) Economic Decay

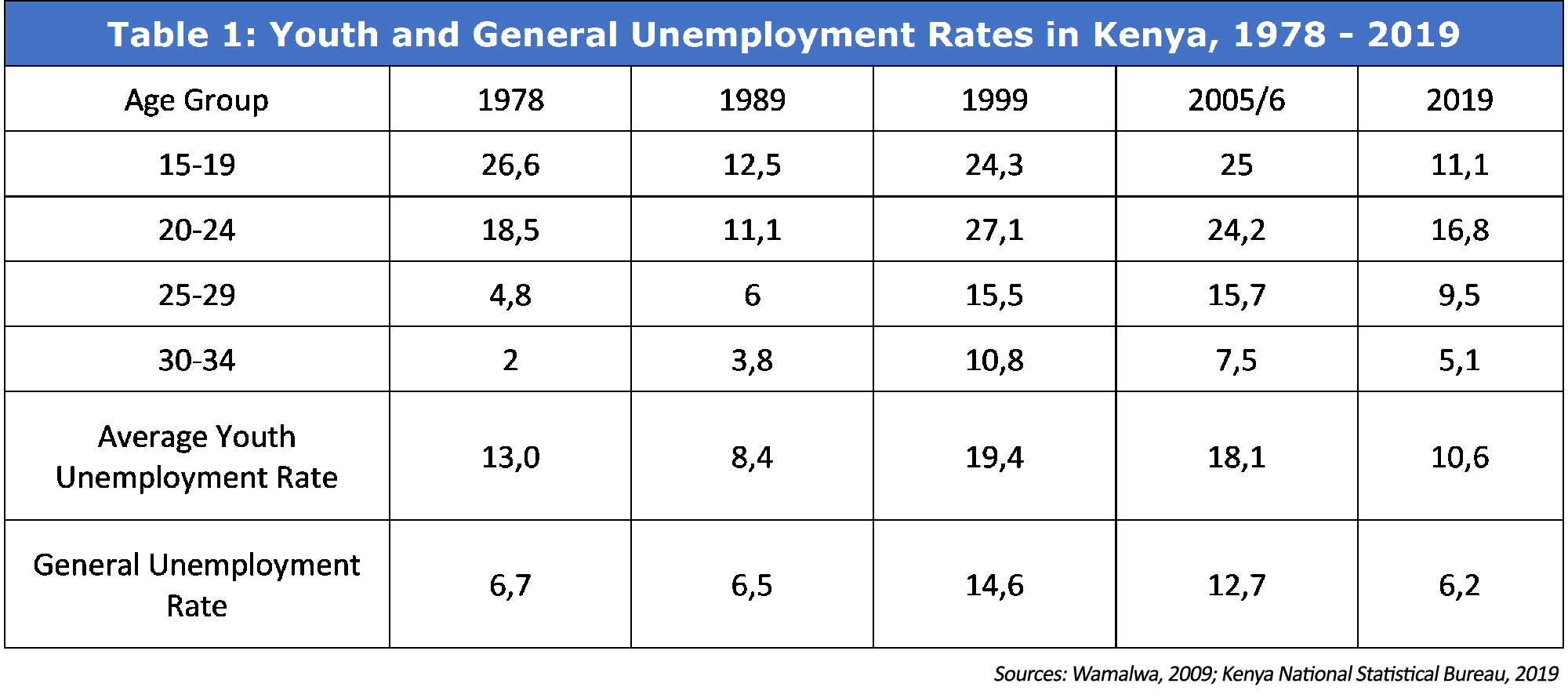

Unemployment in Kenya is challenging, but youth unemployment is even more concerning. According to the Federation of Kenya Employers (FKE), the current youth (15 – 34 year olds) unemployment rate is about 3 times higher than the overall unemployment rate of 12.7 per cent.

This problem is historical. Since 1978, the average youth unemployment rate has typically been substantially higher than the general unemployment rate in Kenya.

As Table 1 shows, the gap seems to have persisted since 1978 when it was 6.3%, dropping to 1.9% in 1989, and rising again to 4.8% in 1999, and further to 5.4% in 2005/6 before dropping to 4.4% in 2019. So the current rates of unemployment are a sharp increase - both in terms of absolute unemployment and the relative rate of unemployment.

The gap between youth and general unemployment is likely to worsen as more than a million young continue to enter into the job market with little skills – many having either dropped out of school or completed school and not enrolled in any college’. FKE suggests that human capital investment inevitably leads to growth and employment. But Kenyan political economists (e.g., wa Gĩthĩnji et al., 2008; Kaminchia, 2014) have long argued that more growth does not necessarily reduce the rate of unemployment. Table 2 seems to bear out their scepticism.

Economic growth in Kenya, however, remains strong (Table 2) and has reached the lower-middle income status. The Kenyan economy is diverse. dynamic and open. It is a preferred entry point for foreign investor and serves the larger East African market. Until COVID-19, Kenya’s economy was one of the fastest-growing in Africa, with an annual average GDP growth of 5.9% (2010 -2018). The growth in the number (~33%) and value (~100%) of shares listed on the Nairobi Stock Exchange within that period, notably from 2011 to 2013 (Lu et al., 2024), complements the picture. But historical rates of unemployment show no consistent downward trend (Table 1). What is entrenched is the poor quality of jobs, endemic inequalities in cities and regions, and harsh conditions in widespread informal economies.

Economic growth in Kenya, however, remains strong (Table 2) and has reached the lower-middle income status. The Kenyan economy is diverse. dynamic and open. It is a preferred entry point for foreign investor and serves the larger East African market. Until COVID-19, Kenya’s economy was one of the fastest-growing in Africa, with an annual average GDP growth of 5.9% (2010 -2018). The growth in the number (~33%) and value (~100%) of shares listed on the Nairobi Stock Exchange within that period, notably from 2011 to 2013 (Lu et al., 2024), complements the picture. But historical rates of unemployment show no consistent downward trend (Table 1). What is entrenched is the poor quality of jobs, endemic inequalities in cities and regions, and harsh conditions in widespread informal economies.

Work by Kenyan economists (Oyvat and wa Gĩthĩnji, 2020) show that most urban youths in Nairobi tend to be immigrants from rural areas. Many others move to Mombasa. The rest go to smaller cities and other rural areas. Many of these relatively new residents are highly educated. By their mobility, they spread inequality, poverty, and unemployment, challenges which characterise life in their destination.

Urban fiction is that it is expectations of higher incomes that drive this migration. As stated by the eminent Kenyan novelist and Nobelist Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1982) - ‘I thought I should go to the capital of Kenya to look for work. Why? Because when money is borrowed from foreign lands, it goes to build Nairobi and the other big towns. As far as we peasants are concerned, all our labour goes to fatten Nairobi and the big towns’ (quoted in Njoh, 2003, p 172). Research (Oyvat and wa Gĩthĩnji, 2020) published in Applied Economics, however, shows that what drives the emigration of rural dwellers is not so much expected higher incomes in cities but inequality in land use, land rent, and land ownership in the country. The trouble is that these inequalities persist in cities too (Obeng-Odoom, 2011, 2020, 2021a, 2021b, 2022), raising questions about how to employ and to accommodate new and long-term residents of the city.

Kenya has tried free money. It has not worked. On the contrary, it has deflected attention from political-economic fundamentals. But what about free trade? A 2011 paper by Moses Kindiki, a Kenyan political economist, revealed how poor the labour conditions in the formal Kenyan apparel industry, the bastion of free trade, were. Another study, conducted in 2021, found that conditions in free-trade enterprises improved slightly. For instance, instead of earning 13.52% of what was paid to expatriates in 2011, Kenyans could earn as much as 15% of the wages of similarly qualified expatriates, but not more. So, for every US$100 paid to expatriates, Kenyans typically got less than US$16 in the export processing zones (EPZ). Also, ‘EPZ firms have been criticized for their harsh working conditions, prevalence of sexual harassment, and limited union representation. Women’s employment conditions, including their lack of long-term employment opportunities, relatively low wages, non-provision of maternity and sick leaves, and long working hours, are all unfavourable to female workers in the sector’ (Owusu and Otiso, 2021, p.30). Nairobi was ranked eight on the Africa100 leading cities list in 2023. But, the Economist Intelligence Unit (2024) estimates that Nairobi will move five places down to 13 by 2035. It seems, therefore, that not only is there persistent unemployment and rising youth unemployment but also general underemployment in Kenyan cities and regions. These sobering findings put to rest the ‘romantic’ visions of free trade and its centrality for economic development.

U-Turn: Policy Cul-de-Sac and Political Settlement

The controversial Finance bill was withdrawn after the threats by the Kenyan President had been rebuffed. Clear that the youth would not hold back, the Presidency stopped holding out. Kenyan activists claim that Kenya does not have a finance problem. It is not, they contend, a question of revenue generation, but accountability of expenditure. For the Kenyan youth, it is the lack of accountability of leadership; failure of leadership; and the burden of too many taxes, which together constitute the problem. The want their leaders to become more accountable. The Government of Kenya responded by bringing the opposition into economist Mushtaq Khan’s notion of ‘political settlement’ – by forming an all-inclusive government. Security on the streets of Nairobi was tightened. The protests remain, but the country’s analysts and activists assess the mood for more protests to have dulled. Technocratic pressure for responsibility and accountability persists.

According to The Economist (2024, p.32), ‘Mr Ruto’s first task will be to find a way of getting Kenya to live within its means…The second is to end community fund-raising drives popularly known as harambees (because they incentivise political corruption). The newspaper seems to endorse how ‘Mr Ruto has responded by scrapping state funding for his wife and slashing the number of special advisers whom cabinet ministers can appoint’ as well as the President’s banning of public officials from taking part in harambees since July 5, 2024. An end to the flaunting of wealth, to distributing cash to ‘stealing’ public resources add to the picture of how good financial governance can save Kenya (The Economist, 2024, p.32). For Kenyan Keynesian economists, however, the emphasis ought to be on public investment and how, that, in turn, can generate multiplier effects (see, for example, Kaminchia, 2014). Perhaps, the two paths could be travelled simultaneously. Maybe not. But either way, a critical question is where to find the money for economic development.

Bad Debt

Kenyans contend that theirs is an odious debt. Why at all did the West lend Kenya the huge sums knowing very well that the money would be misused? Some answers can be gleaned from the research by Leonce Ndikumana and John Boyce (e.g., Ndikumana and Boyce, 2011, 2022). According to them, giving credit is business. What matters is not whether the money would be put to good use but whether credit can create interest.

But Kenya’s debt profile is more complex. ‘The composition and structure of debt has evolved over time’, concludes a Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) working paper (Ochieng et al., 2023). According to KIRPRA, ‘public debt mix changed from 60:40 in 2000 to 52:48 in March 2023 for external to domestic debt, respectively. Furthermore, the domestic debt saw emphasis on long-term government securities. The share of treasury bonds in total domestic debt was 83% in March 2022. Commercial banks are the largest holders of government securities and commercial borrowing has increased through issuance of syndicate loans and sovereign bonds. The share of commercial debt in total external debt rose from 6.3% in June 2000 to a record high of 35.6% in June 2019. Multilateral debt constituted 46.3% of the external debt in March 2022. This leaves only about 18% of debt to be covered by bilateral sources. Here Kenya is 71% indebted to China, only 9% to France, and 4% to Italy as of March 2023. As with Ghana (see Akolgo, 2023), there are questions to ponder structural weakness of the Kenyan economy but also more general questions about monetary sovereignty related to the challenges of holding debt in imperial currencies like the US dollar, the Pound sterling, or the Euro (Coburger, 2023). The resistance is shaky, if it is built only on the case against odious debt.

Other questions are as pressing. For instance, how can the debt be paid off? Also, in what ways can the recurrence of troubling levels of indebtedness be prevented? The Government of Kenya seeks answers in the doctrine of austerity by considering building a lean government, tiny executive, small legislative, and abstemious judiciary. The state would be downsized. In part, that is a reflection of the shadows cast by a well-known specter: the ‘Washington Consensus’ (Williamson, 1993), but it is also a response to the protest. If the resistance is against a big state, then a lean structure is preferable. If the protestors say they cannot pay, then the leaders must pay. National institutions must be downsized; transnational corporations must be supported to facilitate market-led development. But this structural adjustment is like kicking a can down the road or whistling past the graveyard because, as the well-researched reports of the Structural Adjustment Participatory Review International Network (SAPRIN) show, it could increase (e.g., through retrenchment and their cascading effects), not reduce unemployment.

Repudiation is one alternative, but then there is a long-term problem of financing development internally. Also long-term is a case for reparations to be brought under a wider African Union banner for the wrongs of enslaved, indentured, and free labour, for stolen resources, for dispossession of land and for unpaid rents when Kenyan lands were illegally settled.

Taxes and Development

Could a new tax regime provide a path to development? Between the mid-1990s and 2016, tax revenue collection in the median sub-Saharan African country rose from 14 to 18% of GDP. Yet, this rate of increase falls short of what is expected says the the IMF. The shortfall is a function of limited capacity and rent-seeking. Apparently, it is because the governments do not have the expertise and the people do not have the will. Some point to the resource curse - because Africa has so much natural resources, there remains little incentive for the government to widen its tax base. Corruption has been mentioned as chicken and egg conundrum. If taxes are misappropriated, then people don’t pay taxes.

The situation in Kenya is neither an outlier nor proof that African governments are corrupted or incompetent or distrusted. Protesting against taxation has been common in Africa, partly for the reasons offered by orthodoxy, partly for the reasons given by heterodoxy, but particularly because of a long history of rent theft from Africa (for a discussion of ‘rent theft’, see Obeng-Odoom, 2021a, 2021b).

Colonisers and many postcolonial governments in Africa imposed taxes without consultation. Taxation was meant not only to extract revenues but also force Africans into dependence on the cash economy (see, for example, Moore et al., 2018). But Africans resisted when taxes became burdensome. A recent study (Aboagye and Hillbom, 2020), published in African Affairs lists four major tax regimes since 1850s to have triggered popular protests in Ghana. These regimes – from the Poll Tax (1852 -1861), the Income Tax (1931-1944), to the Cocoa Taxation, Compulsory Savings and Sales Tax (1951 -1966), to the Value Added Tax (1995 – 1998) – were all met with massive resistance.

When the Poll Tax was introduced by the colonial government of the Gold Coast (as Ghana was then called before 6th March, 1957), the people of Ghana protested accusing their rulers of being incompetent and wasteful. The government, the protestors contended, had mainly been gallivanting with the finances of the country’, ‘building palatial bungalows…and bringing out officials in large numbers’ (cited in Aboagye and Young, 2020, p. 191).

The post-independence government of Kwame Nkrumah (1957-1966) tried creating youth movements and such like to diffuse opposition and, among others, to use force and build a coalition for such taxes among interested groups. But, in the end, opposition to its taxes contributed to the toppling of the CPP Government in 1966. More recently, there have been protests against VAT, protests against airtime taxes, and protests against value added taxes leading to the e kume/sieme preko demonstrations (Aboagye and Hillbom, 2020), which eventually contributed to toppling the NDC Government. The Aboagye and Hilbom (2020, pp. 178-186) study shows that none of these is sufficient explanation. Political bargaining between the rulers and the ruled to determined when, how much, and how to implement any new taxation regimes.

When the BBC interviewed protesters on the streets of Nairobi they said they would have been amenable to taxation if they had experienced tangible beneficial results from the use of tax revenues. What they were not ready to do is to pay more taxes for nothing. As fundamentally still, taxes which create ‘progress and poverty’ are objectionable. Thus, beneath the puzzle of seeking more taxes are questions of ‘progress and poverty’ (George, 1879/2006). Anyone studying taxation must link it to inequality and to the sources of progress and poverty. What is needed is Progress without Poverty.

This must go hand-in-hand with refocusing the taxation question on transnational corporations (TNC) in Kenya, particularly those whose business models are monopolistic and oligopolistic (Obeng-Odoom, 2021a, 2021b). How much taxes do they pay? What exemptions do they enjoy? How are these used and misused? The infamous ‘Goldenberg Scandal’, involving egregious manipulation of exemption clauses in the name of promoting exports cannot so easily be forgotten. As fundamentally still, that was not an exception or a simple case of corruption. It speaks to a wider issue of the international taxation regime that enables substantial amount of money to leave or leak away from Africa in tax form (Moore et al., 2018).

These need to be addressed collectively by all of Africa. The starting point is to reject the Laffer Theory – the idea that since it is incentives not financial resources that are needed in the development process, states must implement low rates of taxation to increase incentives for development (Laffer, 1981, 2004). Nicholas Kaldor had argued that it is resources not incentives that matter for development (Kaldor, 1963). In practice, TNC contributions to resources-based development have been modest. So the application of the Laffer theory has resulted in less revenue, not more ( Moore et al., 2018). We need to understand Africa urban economies.

Urban and Regional Economics

More taxes could be obtained through effective tax collection. Income taxes in Kenya can be gradually reduced. A paper published in 2018 by Christopher Feather and Chris Meme (2018) argued that nobody in Kenya could obtain decent housing through savings alone. The average bank loan for housing in Kenya averaged 14% between 2010 and 2016. Community savings schemes offered more affordable homes, but their interest rates averaged 12%, which is lower (Feather and Meme, 2018), but about three times higher than what is imposed in cities like Helsinki. Incomes are rather low and such an intervention would help to increase effectiveness of salaries. But the housing problem is also one of rising property values driven largely by speculation. Kenyan cities are ranked third most preferred sites of investment in Africa (Watson, 2014, pp. 9-10). Konza Techno City is a prominent smart city in Nairobi which has generated considerable speculative and investment activities (Watson, 2014, p. 11). The Nairobi 2030 Metro Strategy is aimed at transforming Nairobi into a world, global city. It would likely lead to rising cost of living as is symptomatic of life in such cities around the world.

Signs of challenging days ahead are quite clear. Nairobi has become more and more competitive and speculative. Since 1986, some of the parts of the city have had land values rise over 100 per cent. For example, in Buruburu, the increase in land value between 1982 and 2020 was 178.42%, while in Kilimani, the increase in land value was 2915.67 per cent.

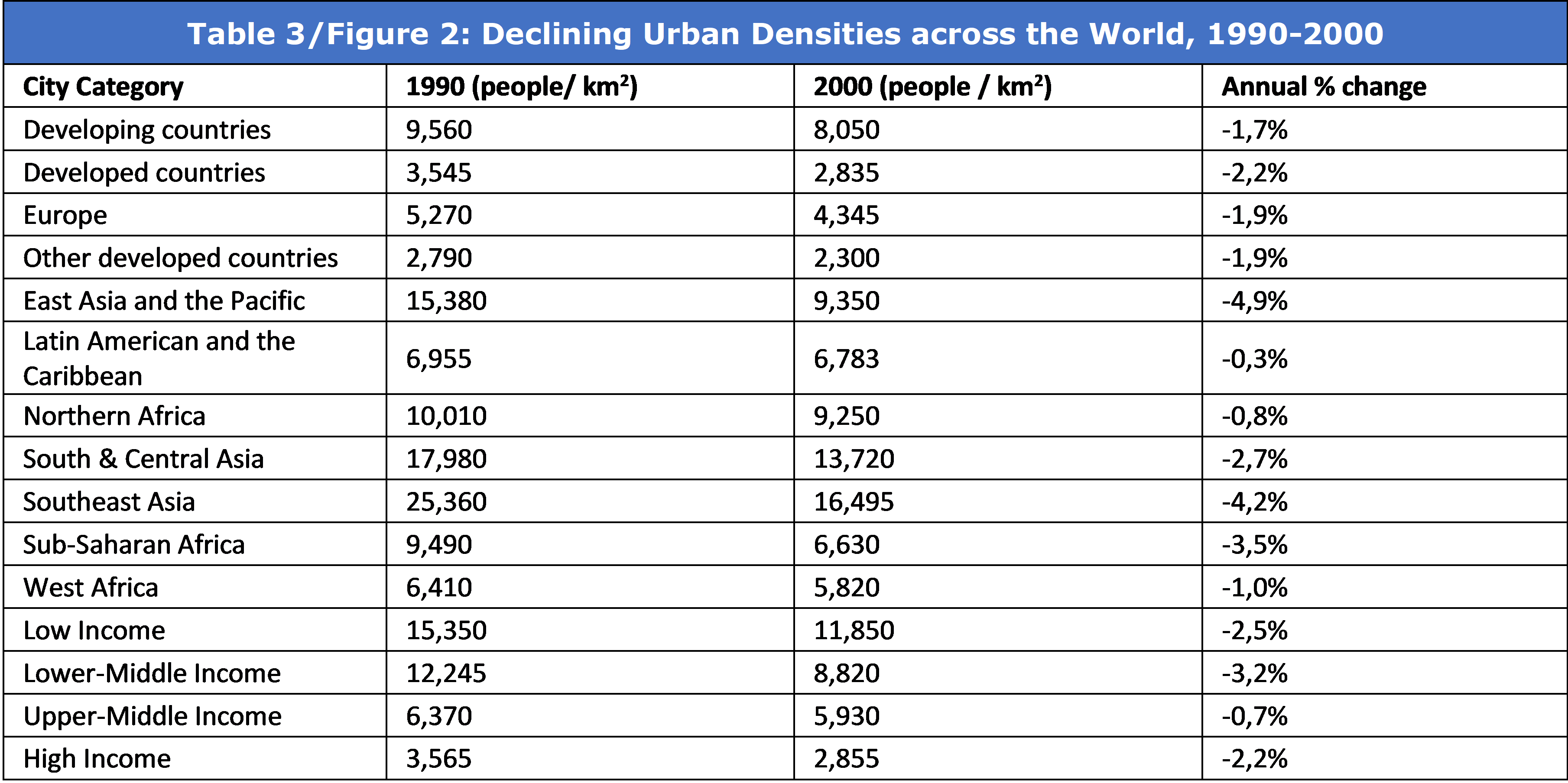

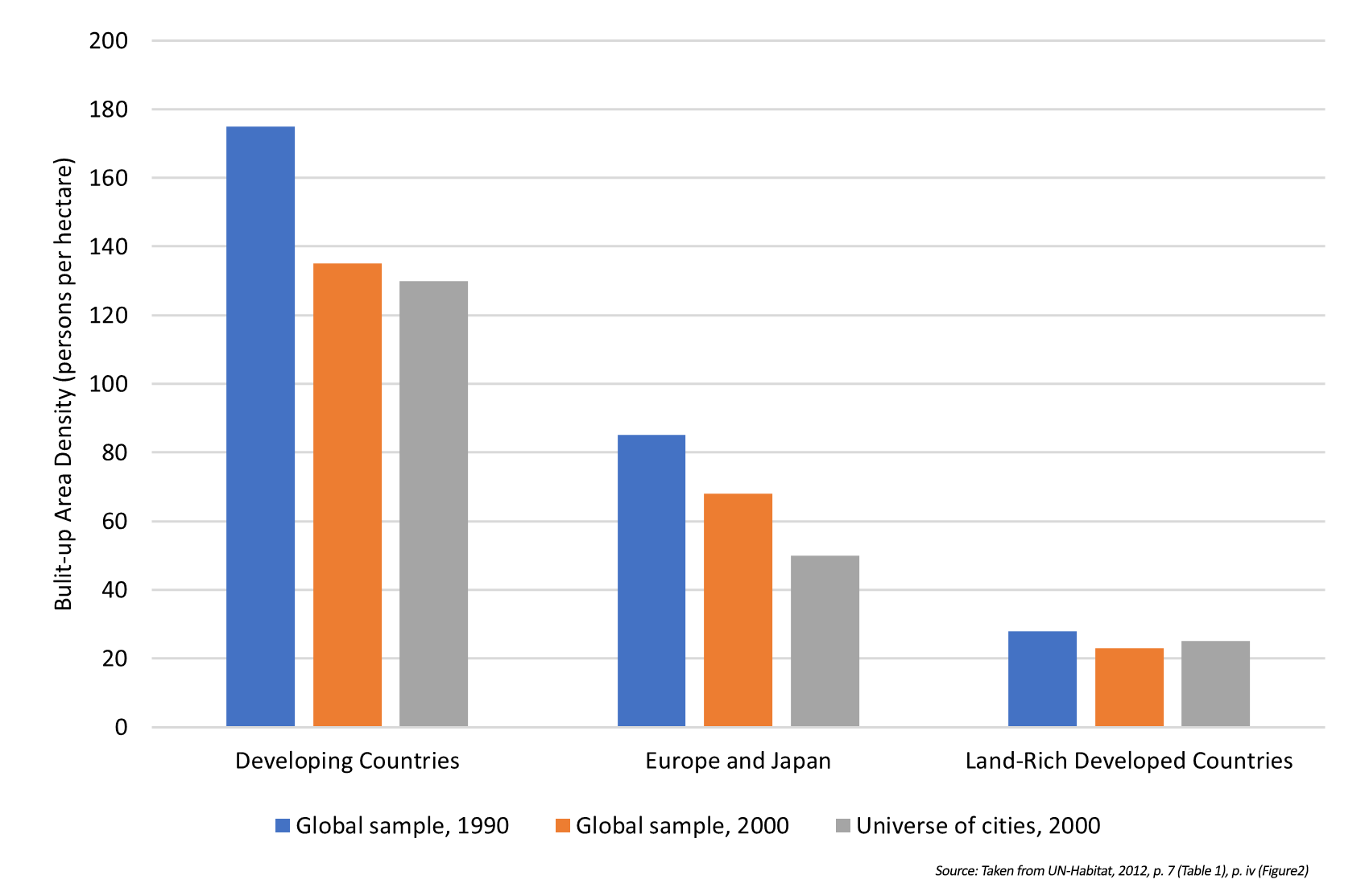

Such rising land values are unecological. Absentee land ownership increases the cost of urban living, drives urban sprawl and reproduces longer, fossil-based commuting patterns. This is a global phenomenon.

As Figure 2 shows, all across the world, sprawl is increasing. But in Africa, it is increasing particularly fast. The annual percent change in urban density in Sub-Saharan Africa is about twice that of Europe and only slightly lower than the average urban density in East and South-East Asia. So, in place of the eliminated income tax could be instituted the land value tax. It is radically different in both their design and incidence. Such taxes would be paid by only landlords whether or not their properties are developed. A land value tax exists today in Nairobi, but it applies only to vacant lands. In a city for which most parts are developed, a land value tax designed this way effectively exempts most of the best properties, in some places, 80% without has failed to bring the city authorities enough revenues. As fundamentally still, this tax design and incidence of tax fail to address questions of spatial inequality, including urban sprawl. As a well-designed land value taxes also serves the purpose of returning land to the commons, the current land value tax in Kenya fails to perform such a role.

As Figure 2 shows, all across the world, sprawl is increasing. But in Africa, it is increasing particularly fast. The annual percent change in urban density in Sub-Saharan Africa is about twice that of Europe and only slightly lower than the average urban density in East and South-East Asia. So, in place of the eliminated income tax could be instituted the land value tax. It is radically different in both their design and incidence. Such taxes would be paid by only landlords whether or not their properties are developed. A land value tax exists today in Nairobi, but it applies only to vacant lands. In a city for which most parts are developed, a land value tax designed this way effectively exempts most of the best properties, in some places, 80% without has failed to bring the city authorities enough revenues. As fundamentally still, this tax design and incidence of tax fail to address questions of spatial inequality, including urban sprawl. As a well-designed land value taxes also serves the purpose of returning land to the commons, the current land value tax in Kenya fails to perform such a role.

The potential of property taxes is known. In Taxing Africa, Moore and his colleagues (2018, pp. 147-177) put the case. But they stress that such taxes constitute less than 0.1 per cent of GDP in Africa (Moore et al., 2018, p. 152). These ‘small taxes’, as Moore and colleagues call them, are the ones that most people in Africa actually pay, because the rest of the taxes are paid by only a minority in formal employment. For the majority of Africans it is these small taxes that they pay, but they speculate that very little is paid because of two key factors: capacity problems and the question of interests, drawing particularly on the empirical work of Tom Goodfellow ( 2017) in Rwanda and Ethiopia. Of the two, the question of competence is less convincing: African valuers have the ability to do quite complex valuations (Obeng-Odoom and Ameyaw, 2011; Obeng-Odoom, 2012). There are design problems and logistical constraints, too (Yeboah and Obeng-Odoom, 2010; Obeng-Odoom, 2010), but a most pressing issue is that of interests, especially those of landlords who have power to obstruct the payment of such taxes (on the power of landlords in Africa, see Owusu-Ansah et al., 2018).

This is also precisely why protestors could strategically focus more attention on landlords who try to avoid the spotlight, disguise their responsibility, and paying their land value taxes. Such taxation is needed because both urban land speculation and property values are rising. These increase go to the core of public policy and common contributions to society. Without them, the real progress in Kenyan society, contributed by the government, others and most ordinary people, will be appropriated only by a few absentee landlords. Redesigning the urban land value taxation to place it on all urban land value, whether occupied or vacant, shifting taxes away from income, and investing the resulting revenues to expand public services, create jobs, provide social protection, and fund both mitigation and adaptation strategies against the onslaught of continuing ecological crises.

More fundamentally still, these strategies could change the fundamentals of the urban economy. Centred on (urban) commons, the Kenyan economy could be placed on the foundations of progress without poverty. Economic and ecological questions would be addressed simultaneously as would political and social problems. Last but not lost nor least is there would be taxation without protests.

Franklin Obeng-Odoom is currently Professor of Global Development Studies at the University of Helsinki, Finland. He is a winner of the Kurt Rothschild Award for Economic Research and Journalism. Contact: franklin.obeng-odoom@helsinki.fi

References

Aboagye P.Y. and Hillbom, E, 2020, ‘Tax bargaining, fiscal contracts, and fiscal capacity in Ghana: A long-term perspective’, African Affairs, vol. 119, issue 475, pp. 177–202.

Akolgo I, 2023, ‘Ghana's Debt Crisis and the Political Economy of Financial Dependence in Africa: History Repeating Itself?’, Development and Change, vol. 54, no. 5, pp. 1264 – 1295.

Coburger C, 2023, ‘When Unification creates hierarchies or, the deadly life of currency unions’, Journal of Law and Political Economy, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 616-625.

Economist Intelligence Unit, 2024, African Cities 2035: Rapid urbanisation and Economic Expansion, Economist Intelligence Unit, London.

Feather C and Meme C.K., 2018,‘Consolidating inclusive housing finance development in Africa: Lessons from Kenyan savings and credit cooperatives’,

African Review of Economics and Finance, vol. 10, issue 1, pp. 82-107.

George H, [1879] 2006, Progress and Poverty, Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, New York.

Goodfellow T, 2017, ‘Taxing property in a neo-developmental state: The Politics of urban land value capture in Rwanda and Ethiopia’, African Affairs, 116(465), 549-572.

Kaldor N, 1963, ‘Taxation for Economic Development’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 1(1), pp. 7-23.

Kamau P and Balongo S, 2024, ‘For the first time in a decade, Kenyans see management of the economy as their most important problem’, Afrobarometer Dispatch, No. 754

Kaminchia S, 2014, ‘‘3Unemployment in Kenya: Some economic factors affecting wage employment’, African Review of Economics and Finance, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 18-40.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), 2019, Quarterly Labour Force Report, Quarter 1, KNBS, Nairobi.

Kindiki M. M, 2011, ‘International Regime Governance and Apparel Labour Upgrading in Export Processing Zones in Urban Kenya’, African Review of Economics and Finance, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 26-40.

Lu X, Zhuang H, Wang J ,Mbugua S,and Holzhauer H, 2023, ‘Calendar Anomalies in the Kenyan Stock Exchange’, African Review of Economics and Finance,https://african-review.com/online-first-details.php?id=82

Maket I, 2024, ‘Analysis of incidence, intensity, and gender perspective of multidimensional urban poverty in Kenya’, Heliyon 10, e30139 , pp. 1-17.

Moore M, Prichard W, and Fjeldstad O-H, 2018, Taxing Africa: Coercion, Reform and Development, Zed Books, London.

Ndikumana, L., & Boyce, J. K. (2011). Africa’s Odious Debts: How Foreign Loans and Capital Flight Bled the Continent. London and New York: Zed Books.

Ndikumana, L., & Boyce, J. K., eds, 2022, On the Trail of Capital Flight from Africa: the Takers and the Enablers, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Njeru, J. 2006. “The Urban Political Ecology of Plastic Bag Waste Problem in Nairobi, Kenya,” Geoforum, vol. 37, pp.1046–1058.

Njoh, A. 2003. “Urbanization and Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Cities 20(3): 167–174.

Nyabwengi L, K’Akumu O.A., and Kimani M, 2020, ‘An Evaluation of the Property Valuation Process for County Government Property Taxation, Nairobi City’, Africa Habitat Review Journal, volume 14 Issue 1, pp. 1731 - 1743

Obeng-Odoom F and Ameyaw S, 2011, ‘The state of surveying in Africa: A Ghanaian Perspective’, Property Management, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 262–284.

Obeng-Odoom F, 2010, ‘Is decentralisation in Ghana pro-poor?’, Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, Issue 6, pp. 120–126.

Obeng-Odoom F, 2011, ‘Urbanity, urbanism, and urbanisation in Africa’, African Review of Economics and Finance, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–7.

Obeng-Odoom F, 2012, ‘Good property valuation in emerging real estate markets? Evidence from Ghana’, Surveying and Built Environment, vol. 22, pp. 37–60.

Obeng-Odoom F, 2020, Property, Institutions, and Social Stratification in Africa, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

Obeng-Odoom F, 2021a, The Commons in an Age of Uncertainty: Decolonizing Nature, Economy, and Society, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Obeng-Odoom F, 2021b, ‘Oil Cities in Africa: Beyond Just Transition’, American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 777–821.

Obeng-Odoom F, 2022, Global Migration Beyond Limits: Ecology, Economics, and Political Economy, Oxford University Press, Oxford

Ochieng J, Chemnyongoi H, Omanyo, D, Kiriga B, and Nato, J, 2023, ‘Public Debt in Kenya: Management and Sustainability’, Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis KIPPRA Working Paper No. 33.

Otiso, K.M., Owusu, G., 2008, ‘Comparative urbanization in Ghana and Kenya in time and space’, GeoJournal, vol. 71, pp. 143–157.

Owusu F and Otiso K.M., 2021, ‘Twenty Years of the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA): Policy Lessons from Kenya’s Experience’, Kenya Studies Review, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 16 -34.

Owusu-Ansah A, Ohemeng-Mensah D, Talinbe R, and Obeng-Odoom F, 2018, ‘Public choice theory and rental housing: an examination of rental housing contracts in Ghana’, Housing Studies, vol. 33, no. 6, pp. 938–959.

Oyvat C and wa Gĩthĩnji M, 2020, ‘Migration in Kenya: beyond Harris-Todaro’, International Review of Applied Economics, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 4-35.

Schimmelpfennig A (2019), ‘Collecting Taxes’, Finance and Development Magazine, March, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2019/03/book-review-taxing-africa-schimmelpfennig (accessed 1 July, 2024)

The Economist, 2024, ‘Unrest in Kenya: Zacchaeus climbs down’ in “How to Raise the World’s IQ”, The Economist, July 13th -19th 2024.

UN-Habitat, 2012, Leveraging Density: Urban Patterns for a Green Economy, UN-HABITAT, Nairobi.

wa Gĩthĩnji M, Pollin R and Heintz J, 2008, An Employment-Targeted Economic Plan for Kenya Edward Elgar, Cheltingham.

Wamalwa F.M., 2009, ‘Youth Unemployment in Kenya: Its Nature and Covariates’, The Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA), Discussion Paper No. 103 of 2009 on Youth Unemployment in Kenya: Its Nature and Covariates

Wamalwa, F.M. and Burns J, 2018, ‘Private schools and student learning achievements in Kenya’, Economics of Education Review, Volume 66, pp. 114-124,

Watson, V. 2014. ‘African urban fantasies: Dreams or nightmares?’ Environment and Urbanization 26(1): 215–231.

Williamson J, 1993, “Democracy and the ‘Washington Consensus’”, World Development, vol. 21, no. 8, pp. 1329 – 1336.

Yeboah E and Obeng-Odoom F, 2010, ‘“We are not the only ones to blame”: District Assemblies’ perspectives on the state of planning in Ghana’, Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, issue 7, pp. 78–9