Daring to Dream Beyond – Teaching in the 21st Century

The future is unknown, now more so than any other time in our short history. Many have described the current epoch in which we live as Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous (VUCA). The conditions, challenges, settings and contexts that we exist in change so rapidly, we cannot even predict what jobs will exist, or even be in trend, in the next ten years. Our systems and institutions are rapidly trying to adapt to these constant shifts in the winds, but what happens when an organisation that takes years to enact change, is suddenly compelled to pivot their strategic direction? How does that affect the individual? How do we deal with the chaotic changes happening all around us?

Amidst these difficult questions and a seemingly volatile future,

we educators are tasked with not just figuring out what changes will happen in the future, but also preparing our students for this unknown variable.

The question of what qualities, skills and abilities students of the 21st century need is

not something novel to us as educators. Many authors have written about the subject of what is necessary for people to survive and thrive in the future, but for a more localised context, I draw your attention to the 21st Century Competencies developed

by the Ministry of Education (MOE, 2021).

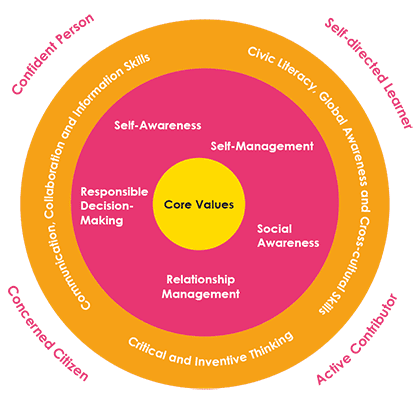

The 21st Century Competencies framework designed by MOE.

At the centre of every student should be a heart that guides how they live and who they choose to be. Core values are thus the compass that guides each person in making choices for a kinder world. As such, to help themselves attain said core values, educators need to inculcate students’ social-emotional competencies – personal intrinsic skills that, with proper guidance, shape them into the people they should be. However, to change the world around them, our students will need critical thinking skills that allow them to be, make and see connections between both disciplines and people. Our hope for the future is that our students become compassionate people capable of seeing the world for what it is, what it can be, and what it should be, thus setting out to etch out their own vision for the future.

The bigger question will be this: how do we set out accomplishing this?

Achieving the 21st Century Competencies – How?

As someone who has always wanted to be a teacher since I was 18, I have realised that despite the multitude of professions and discourses out there, everyone is interested in education. After all, almost everyone has had one, and everyone has had some experiences and encounters with teachers, with the schooling system and with the environment that comes with it. Sharing that I want to be/am a teacher always elicits stories about other people’s education, the teachers they loved and hated, and some of the lasting memories of halcyon days. As a younger adult, the stories I heard tended to be mostly positive, with some doses of negative experiences in them. However, as I grew older, I started to hear more diverse views of people who could not fit within a narrow definition of success and of people whose talents were not appreciated fully. An encik from the army once told me he hated his education because his path in life was determined by a single acronym: EM3. A close friend always felt that she learnt everything by herself because her education was inadequate. These are stories of people who fell through the cracks and did not benefit from what is supposed to be “the great equaliser”.

All of the stories I have heard made me grow as a teacher and see the flaws in both the system and my own teaching style. Since then, I have always kept their stories in mind as I teach. I also find myself imagining hypothetical scenarios: if these individuals were my students, could I reach out to them? Most importantly, these stories taught me that we live within echo chambers and develop blind spots based on the people we interact with. If we allow ourselves to continue living within these biases, we will never hear the stories of those who did not benefit from their education; we will not grow as teachers. These stories taught me the value of thinking out of the box, and to study and understand better what we do not know. In order to understand the education system and why some people fit in better than others, I started by asking myself a single, important question:

Why do some people learn better than others?

The question is multidisciplinary in nature. Is it social inequalities that entrench asymmetrical benefits between students? Is it neurological, cognitive differences? Is it a case of different pedagogies interacting with individual differences? Or, perchance, the system defines and assesses our students too narrowly? These various questions led me to research and inquire about the nature of learning and how we can enhance it for our students. In particular, I was drawn to the idea of 'teaching' creativity and how we can nurture a generation of it. In my undergraduate years, I conducted a research project (Chong, 2020) in several local schools regarding the relationship between motivation, divergent thinking, and a teacher’s desire for creative students. What I discovered from surveying over a hundred students and their teachers is that teachers play a large role in nurturing creativity in their students. Generally, research has shown that teachers do not like having creative students in their classes as the traits associated with such students tend to be those disruptive to the traditional classroom (Westby & Dawson, 1995). However, my findings showed that teachers with a strong desire for such students actually nurture students with greater divergent thinking.

Understanding these findings as both researcher and educator, I realise that there is so much about learning that is dependent on myself, my own abilities, my own beliefs and my own desires. As cheesy, overused and clichéd as it sounds, the teacher makes the biggest difference. Now, having finally become one, there are bigger questions that I must ask of myself and of my peers. Just as we hope our students will look within themselves first before changing the world, we as future educators must also reflect upon the nature of our craft and seek to ask ourselves – who must we become to lead our charges into the new world? What competencies must we possess to develop the skills we desire to see in our students? What people do we have to be to create an education system that embraces true diversity?

Connections and creations – teaching skills for an interconnected world

Just as our students will need relevant thinking skills to change the world, we too will need certain special thinking skills to craft our curriculum and guide our students. In Bruno Latour’s book, ‘We Have Never Been Modern’, he begins with a description of a newspaper and the typical articles one could find:

“I learn that…the hole in the ozone layer is growing ominously larger. Reading on, I turn from upper-atmosphere chemists to Chief Executive Officers of Atochem and Monsanto…”

He goes on to describe the rest of the article, summarising it by the statement:

“The same article mixes together chemical reactions and political relations. A single thread links the most esoteric sciences and the most sordid politics.” (Latour, 1993, pg. 1)

Latour uses this to describe how distinctions between the scientific and cultural are complexly intertwined, using this as a prelude to how we might reorientate the way we view our natural and non-natural world. Although written for the early 1990s, Latour’s ideas ring even more truly in the 21st century, where we are starting to see the complex, changing and critical nature of social and natural issues that require unique solutions. Open your newspaper, and you will see many articles, just like the one Latour describes, which draws from the knowledge and perspectives of different disciplines. The future is a series of hybrid networks, and we must be equipped to view the world from such a lens if we are to help our students see the world the same way.

National University

of Singapore (NUS) President Tan Eng Chye has suggested that facing such a future will “require integrating knowledge, skills and insights from different disciplines” (Tan, 2020). The acknowledgement of this vital shift required in our education

system has sparked several major changes in higher levels of education. Since 2020, NUS has announced the formation of several interdisciplinary colleges: the NUS College, a combination of the University Scholars Programme (USP) and Yale-NUS, the College

of Design and Engineering, as well as the College of Humanities and Sciences. Courses in universities, such as Cognitive Sciences in the University of Southern California (USC) and Global Studies in NUS are also examples of university courses whose curricula

require students to study modules from different disciplines.

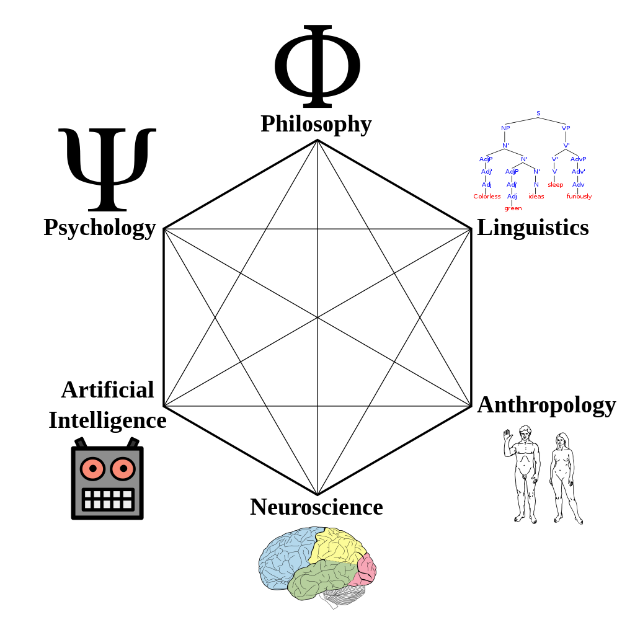

Cognitive Sciences: An interdisciplinary study of the mind and its processes. Several universities such as USC offer this as a course of study (Miller, 2003).

Cognitive Sciences: An interdisciplinary study of the mind and its processes. Several universities such as USC offer this as a course of study (Miller, 2003).

Yet, despite this trend, interdisciplinary education remains rather absent within Singapore’s mainstream education, both in primary and secondary levels. We could argue about what MOE or our various curriculum branches should be doing, but understandably, it is a highly difficult task. A substantive change to our educational system, such as the one we are seeing in NUS, poses a variety of challenges related to time, resources and coordination. Imagine a curriculum specialist having to curate a mathematics syllabus, followed by coordinating with another specialist in the science department. When their work is done, they would have to seek multiple approvals, probably from a committee of multidisciplinary educators, on top of some additional training that would probably be required by the ministry for educators. The more actors involved, the longer change will take. Can educational institutions pivot in time to train our students to face future problems?

It's a good question to ponder. What we can do to get the gears turning is not to wait for things to happen, but to take things into our own hands and start experimenting. I propose a ground up movement to integrate interdisciplinary education into our lessons and schemes of work. An interdisciplinary approach to education is not something that requires us to take another course or diploma; we simply need to keep our eyes and minds open to the connections that exist in our world. Our job requires active engagement with content from our own disciplines and constructing frameworks for students to adopt such paradigms to facilitate a similar engagement. However, as seen above, our own disciplines do not exist in silos, and when we engage with our content, we also come into contact with other areas of knowledge. This happens all the time in our lives. As an English Language teacher, I have seen how language is used to unpack scientific jargons in order to communicate easily digestible scientific facts about COVID-19 to the world. Evocative, emotive language is utilised to a tee to compel excitement and patriotism in World Cup commentaries. Even in History, nuanced and targeted choice of words can create different historical narratives and theses. The seemingly individual content-silos of Science, Physical Education and History belie intrinsic, lexical connections calibrated to suit specific contexts. Once we start seeing the connections between our discipline and others, all we need to do is think about how these areas relate to our own field of expertise and weave them into our lessons.

I realised this during my contract teaching years as I taught both Social Studies and English Language. In both subjects, the skill of inference is important in understanding the subtext in an author’s words or graphics. However, I realised that both teachers and students saw it as two separate skills, one to apply in comprehension passages, and the other to source based questions. This was because they used different frameworks, and no one ever made a reference to the other subject to indicate that both skills were similar/the same. The way our subjects are framed also frames our ways of thinking, and perhaps we need to think out of the box to help students make this connection.

I decided to attempt something – look for the similarities in both frameworks and try to teach Social Studies inference skills the way I teach English inference skills. Traditionally, we teach students to adopt the inference-example-explanation framework in Social Studies. However, in terms of thinking, we interpret what we read/see first before deriving its meaning, something we teach more explicitly in English. I therefore tried to implement an example-explanation-inference framework instead, which might be more aligned with the thinking process students would engage with. Another example was when I saw my students coming back from a Food and Consumer Education (FCE) class with posters they had made in hand. They had designed them as part of an activity to promote and advertise healthy eating. I instantly saw a link between this and visual text elements I taught in English classes. Using that as a launchpad, I linked their learning points from that lesson (which I derived from the students) to the elements of visual texts that I could teach.

However, we also need to acknowledge the shortcomings many of us educators will have as specialists. We may not be able to see these links because we do not have a complete level of understanding of another discipline. To expect ourselves to be experts in other fields is also demanding the impossible in a climate where teachers are overworked and overloaded. The key is that we teachers also do not exist in silos as well, and to make this happen, we need to communicate and work with other people: not just with other teachers, but students as well. As university graduates, teachers have become subject specialists, focusing on a niche topic of interest. Students, on the other hand, are still at a stage of their education where they are exposed to a broad variety of topics. This is where a true student-centric education can be realised – by close collaboration with students as subject matter experts in various other fields. While depending on them for context and knowledge, I provide my unique perspective as a subject specialist together with my ability to connect ideas together. As I did in my classes, I questioned and learnt what students were learning from their other subject teachers. This serves two purposes – firstly, memory recall for other subjects is being done. Secondly, it allows me to see where they have come from and start drawing connections from those subjects to mine. In such a model of education and questioning, teachers and students truly work together in collaboration in order to come to a greater understanding of knowledge. What an exciting idea!

Of course, the ad-hoc connections we teachers make in our class can only bring us so far. The next level of such a pedagogical approach would be to collaborate with other teachers to intentionally bring these connections together, possibly through a joint problem-based project, or joint lessons. One interesting lesson I sat through in Junior College was when my General Paper (GP) tutor arranged for three science teachers from Biology, Chemistry and Physics to sit in for a class debate on the morality of science. While the focus was on answering more philosophical questions aimed at answering essay questions, their perspectives helped to draw connections and see things in a new light. In university, this happens frequently as well, when guest lecturers come in as subject matter experts to weigh in on a topic that, while tangentially relevant, helps to bring in new perspectives.

Finally, the last frontier that is within each school’s control are joint problem-based projects that could utilise the subject knowledge from all subjects learnt in school. Catholic Junior College (CJC) does this

through their Ignite programme, where students will gather once a year and combine knowledge from different fields through a series of seminars and projects they will enact. The project usually focuses on a social problem that may plague a local community.

Borrowing from both humanitarian and scientific approaches, students learn how they can produce a holistic solution in an authentic context. Such programmes should be the future of our local education, and in fact, there is plenty of room within current

programmes to implement this. Many schools are rolling out Applied Learning Programmes where students learn other skills and apply their knowledge to them. If we make the links to our current curriculums more explicit, we would have come full circle.

The best part of all of this? It does not require us educators to wait for a long-term policy change in organisational or curricular structure. Interdisciplinary education can start with us and how we see things.

Seeing things in a different

light is to be creative, and the teacher of the 21st century must be creative in his/her methods, actions, and outlook. Making connections between people and subjects requires us to create new perspectives for ourselves, and a huge part of that is our

imaginative outlooks – to see what does not exist. I think the first step to increasing our creativity is to clarify certain debilitating misconceptions about creativity. There are many misconceptions that people have about creativity, but I believe

the most debilitating and harmful of them is that only certain groups of people are creative, specifically people within the arts, and people who have created great works or generated brilliant ideas; people think that creativity only exists on the highest

levels of thinking or product development.

People would use Mozart and Van Gogh as examples of creative people because they are artists and have both produced revolutionary works that are praised widely. While they certainly are, it does not mean that the average painter, scientist or student is not creative. Kaufman and Beghetto’s (2009) 4C model of creativity divides creativity into four levels. Geniuses like Sir Tim Berners-Lee and Dr Marie Curie probably exist on the highest level, known as Big-C levels of creativity. People at this level have probably generated ideas or works that revolutionise and contribute massively to a particular field. However, even the little “a-ha!” moments that we have in our daily lives count as creativity. At the Mini-C level of creativity, a small and meaningful discovery or way of doing things counts as being creative. For example, while a student’s discovery of recycling a plastic bottle to grow plants may not be groundbreaking per se, it could be the most meaningfully creative thing in his or her life so far.

This misconception has two potentially huge consequences for us as educators. The first is that we assume our students are not creative, or that only smart students can be creative [1]. This is completely untrue and multiple studies have shown that the links between intelligence and creative thinking are tenuous at best (Kyung, 2005). If we believe that only select students can be creative, then our biases will seep into our treatment of both lessons and students, resulting in lowered divergent thinking. Our beliefs can shape our reality, and we should not allow ourselves to fall into a self-fulfilling prophecy (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 2003). Instead, we can start to see and encourage the small levels of creativity in their work, or even get students to reflect upon these mini “a-ha!” moments. We should affirm students when they tell us of these discoveries, and we should also encourage students to think widely. For example, how can they draw from any source to help them in this current predicament?

A second consequence is that we believe our own teaching [2] cannot be creative. During my Postgraduate Diploma in Education (PGDE) course, I once heard in a microteaching lesson that creativity could not be measured, and thus would be difficult to define as a lesson objective. While obviously an ungrounded assertion to make, statements like this show how preconceptions teachers have of creativity can affect a lesson, starting from its conceptualisation and design. This idea links two separate concepts – the Pygmalion-Rosenthal effect, better known as the self-fulfilling prophecy, and an idea known as creative self-efficacy. The self-belief in our creativity is known as creative self-efficacy (CSE) and a positive correlation between various measures of creativity and CSE has been shown (Haase et al., 2018). Our beliefs about creativity will affect both creative teaching and teaching for creativity, concepts that are necessary for the interdisciplinary education that must take place for our students. If we do not believe we can be creative in our teaching, then we never will be. This does not mean our teaching needs to cultivate Mozarts and Beethovens; all we need to do is start small. Creativity research generally looks at processes or products in order to measure creativity, and that is something we can begin with. Start by trying to think out of the box as well, in terms of your own lesson designs and measures. Often, success begets success, and these things can do wonders for your own creative self-efficacy.

With creativity and connections (interdisciplinary and otherwise), teachers and our students will have the know-how to solve future problems, even if they are not known to us at the present moment. However, one final vital ingredient needs to be added – inculcating a moral compass to guide these actions. How can we set out teaching students to build their own compass? What are our own moral compasses? Why do we need to build a kinder, gentler world?

A moral compass – What path do we set out on?

If we simply taught students the skills mentioned above and left them to face the world, we risk leaving the most important aspect up to chance – their sense of morality. They could use their skills to manipulate people or systems into doing their bidding all for their own benefit. Perhaps they might become an instigator of the problems we did not foresee. I do not mean to fearmonger, but these are possibilities if we do not provide students with a framework to distinguish right and wrong, especially in a world where morality goes far beyond the binary constructs we sometimes reduce them to.

We hope that our students will be able to use their skills and habits for good, but what does ‘good’ mean in this day and age? It is not that our learned ideas of morality are antiquated and obsolete. However, the times and settings that we, our students included, find ourselves in have given rise to changing concerns, worries and thoughts about the future. Take, for example, an increasing dissatisfaction with the idea of work and its place in a capitalist society. Movements such as ‘quiet quitting’ and ‘anti-work’ have shown that people are rebelling against the nature of hustle culture and the rat race to carve a new path for themselves. Is that the right way to go? Should we instead encourage the truism of ‘head down, keep going’? Another example could be the increasing ideas of nihilism and existentialism – that increasingly, dissatisfaction with life in general is leading to more young people identifying that life has no meaning. Do we just counter these thoughts with a “No! That’s absolutely not true!”? How can we guide students to navigate the large-scale cultures and movements that exist out there?

The point of bringing these points and questions up is not to find answers – after all, many of us are, too, grappling with these ideas and situations. The greater fear for us teachers is that a lack of awareness leads us to respond in a matter that alienates us from students. If we are unaware of these issues, or lack conceptual knowledge about said issues, we will end up as lost as they are. In the midst of being co-constructors of knowledge with our students, we need to ensure that we do not end up charting a path without listening to their concerns or worries. So often, we see young people not listening to their elders because they feel their perspectives, needs and feelings are invalidated and not considered. They start to think that the adults do not know anything, because it seems like they aren’t listening.

We must ensure that we ourselves have the right concepts, tools and knowledge to guide our students in answering and navigating some of these unknown concepts. What are the core values we hold dear and true to our hearts? What are some of the values that society around us values too? What are some of the considerations and values of people of this day and age? How can we reconcile some of these differences? Only by questioning our own morality, the biases we possess and the contexts we live in, can we begin to grow and learn with our students. These are essential tools to then help students recalibrate their moral compass and understand how to navigate in a VUCA world.

A 21st Century Educator – Creative, Critical, Caring and Courageous

What is essential for teachers in this 21st century is based on an axiom, of which I am a devotee: that we teachers are far from being the sole arbiters of knowledge. People, whether they be students, children, highly educatedor non-educated, all possess knowledge of all sorts. If we place ourselves on the pedestal and entrench the misconception that teachers are unerring arbiters of knowledge, we invariably impose knowledge, values and skills rather than inspire and motivate learning such values in our students. In this day and age, the greatest consequence of dismissing the knowledge of a student is alienation – that our students no longer respect our views and start seeking other ‘sources of knowledge’. We need to understand that our role as educators has changed into one of a co-constructor of knowledge, that we take in knowledge, concepts and ideas from various realms and sources, and we reconceptualise, ideate and recompose it such that our students can learn from all of it. We are a nexus point, a connector between all these various ideas and people, so that our students can learn in a safe and comprehensible manner.

We need to understand that our role as educators has changed into one of a co-constructor of knowledge, that we take in knowledge, concepts and ideas from various realms and sources, and we reconceptualise, ideate and recompose it such that our students can learn from all of it.

To act as this nexus point, we must always remain connected to the world around us. We must understand what others in other disciplines are saying, and how that can relate to our own discipline. This will require seeing the world in new and unique ways, and brainstorming new ways of thinking for our students. Richard Feynman, the famous Caltech lecturer and physicist, was known to be able to twist and turn concepts and help those around him see these ideas in a new, fun and interesting light. That, to me, is the model of what we should be doing as teachers, and that comes from a place where we experiment and toy around with concepts to produce something new and novel.

Some of us might, at this point, feel sceptical and afraid. The novel is often the unknown as well, and to fail in our lessons might mean our students do not learn. However, the beauty in co-construction is this: if we create an educational culture where we learn and teach each other as equals, our failures and setbacks also become learning points for our students. We do not confront our mistakes as defects to be hidden from students, but as points to be addressed and worked on together. Let’s say a new way of looking at sentence structure composition falls flat with a class, to work on it with them would be to say, ‘Alright class, which sections of this do not match with what you already know? How else can we see it?’, and thus work together to form a theory or understanding of sentence formation that makes sense for everyone. We learn a new way of teaching students, and the students learn a new way of looking at the subject.

This highlights the final value I believe that we need as teachers of the 21st century: courage. We exist in a landscape where many of us value stability and safety, and rightly so. These values carry us in the classroom as well – what has been tried and tested will bring the students to where they need to be. We continue to construct a world that is much like the one we knew because it is all we know; it is what brings us comfort and security. But I reject that. If we want to develop an education system that accepts everyone, that nurtures creativity and morality, that will help our students craft a kinder and better world, we will need to think outside of the box, and rethink how we are teaching. We must first dare to dream of the wild and crazy ideas. Only after do we allow our realism to ground us, not the other way around, as many do. The only limits are those we set with our moral understanding of the world, the only restrictions are those that will cause harm and injustice to others. Only by working as equals in the realm of knowledge, by thinking above and beyond our current roles as teachers can we set ourselves free to guide students to think and see further than we can and help them take the future into their own hands.

If we want to develop an education system that accepts everyone, that nurtures creativity and morality, that will help our students craft a kinder and better world, we will need to think outside of the box, and rethink how we are teaching.

The role of the teacher is, as always, paramount to the future of our world. It is time we reinvent and reconceptualise what it means to be a teacher.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl,

D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete ed). Longman.

Chong, X. Y. I. (2020). Motivation and Desire: An Exploratory Analysis of Factors

Influencing Teaching for Creativity [Thesis]. https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/176669

Haase, J., Hoff, E. V., Hanel, P. H. P., & Innes-Ker, Å. (2018). A Meta-Analysis of the Relation between Creative Self-Efficacy and Different

Creativity Measurements. Creativity Research Journal, 30(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2018.1411436

Catholic Junior College. (2015). Ignite Programme. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://cjc.moe.edu.sg/eopenhouse/academic-information/signature-programmes/ignite-programme

Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688

Kyung, H. K. (2005). Can Only Intelligent People

Be Creative? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 16(2–3), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2005-473

Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Harvard University Press.

Miller, G. A. (2003).

The cognitive revolution: A historical perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 141–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00029-9

Ministry of Education. (2021). 21st Century Competencies. Base. http://www.moe.gov.sg/education-in-sg/21st-century-competencies

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (2003). Pygmalion in the Classroom: Teacher Expectation and Pupil’s Intellectual Development (Newly expanded ed). Crown House.

Tan, E. C. (2020). Universities need to tear down subject silos.

The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/universities-need-to-tear-down-subject-silos

Westby, E. L., & Dawson, V. L. (1995). Creativity: Asset or Burden in the Classroom? Creativity Research Journal, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj0801_1

[1] The misconception commonly comes from Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), which indicates that creativity is a higher order thinking skill. Many people thus assume that this means greater intelligence is required for people to be creative.

[2] A distinction should be made here between teaching for creativity, which is teaching with creativity as a lesson objective, and teaching creatively, meaning to teach in a new and interesting manner.

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)