Building Bridges into the Future

My teaching philosophy is “Building bridges into the future”.

Bridges have always fascinated the literati. The Americans Arthur Miller and Hart Crane were inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge: an engineering feat that connects Manhattan

and Brooklyn in New York City, and once the longest suspension bridge in the world. This feat of connection motivated Crane’s modernist epic, The Bridge (1930). To quote my favourite lines:

thy swift

Unfractioned idiom, immaculate sigh of stars,

Beading thy path—condense eternity:

And we have seen night lifted in thine arms.

We see the great lengths that people go to in our search for connection, building bridges that can “condense eternity”

– as the distances that separate us from each other can sometimes feel like. As an “unfractioned idiom”, bridges offer a powerful image of wholeness and integrity that buoy and “lift” us, as they overcome division and

separation.

Bridges also moved an English poet whom I studied for the GCE ‘A’ Levels. Philip Larkin, famous for his suspicion of sentimentality, nonetheless wryly observed that “Always it is by bridges that we live”.

Connections sustain us, and this key element of connection is again found in our figures of speech used to describe human relationships – to bridge the gap, building bridges, to be the bridge.

The use of an architectural metaphor

to inform my teaching philosophy stems from my formative undergraduate years at Durham University. Durham is a peninsular city in Northern England, bounded on three sides by the River Wear’s meanders. This means that the city’s famous

bridges featured prominently in my daily commutes between home, lecture sites and town.

Baths Bridge

My favourite remains Baths Bridge (1960s). A diminutive, gently sloping bridge, it provides a picturesque vantage point for pedestrians to observe rowers passing underneath. On days I sought a scenic route back home from the city, I would cross Baths Bridge, where often there was a gorgeous, pink-hued sunset waiting to be beheld.

I speak fondly of these bridges because my undergraduate years marked a turn in my professional and personal identities as a teacher. Indeed, the many walks and repeated crossings-over of these bridges gave me time and space to explore this identity.

Up until I entered university, I was firmly set in my decision to be a teacher. I knew that I wanted to play a part in nurturing the next generation and pass on my love of Literature. In 2016, just before leaving Singapore, I posted on Instagram that I wanted my future students to be “secure in the knowledge” that our “experiences are what makes us unique and precious to somebody out there”. I firmly believed that school was the ideal testing ground for life, giving students the space and latitude to discover their strengths, passions, and dreams.

These beliefs were to be severely tested in the years to follow.

At its core, my eyes had been opened to how imperceptibly vast the world is. Despite engaging with Literature and History (both regional and international) during Junior College, I wasn’t prepared for how different life would be in an English medieval city, in comparison to Singapore’s urban clamour.

From a country that counts the airport as one of its top leisure destinations (especially for east-siders), I had moved to a country where walks along the river to find a bluebell forest counted as one of its keenest pleasures. Instead of embracing new and exciting possibilities, I instead confronted that other side of the new: longing for the familiar, resisting change and turning inwards.

Life-long learning | Being open

In that sense, the greatest bridge I crossed was located far away from Durham. Instead, it was at Changi Airport. I always felt a sense of trepidation as I crossed the jet bridges to board the airplane. I found it hard to say goodbye to my loved ones at the departure gates, and I dreaded leaving the familiarity of Singapore.

That intimate experience of fear has firmly influenced my teaching philosophy today. A teacher needs to be a bridge for students, as they traverse worlds both old and new.

NIE offers a “Four-Life” model that sets out the principles underlying purposeful teaching and learning (Kwek et al., 2017). These four aspects aptly enrich the metaphor underlying my teaching philosophy.

The first aspect of bridging relates to life-long learning. One key takeaway from QED52A Educational Psychology is that students are adolescents negotiating their identities for adulthood, with the support of peers and teachers. While this can be a time of uncertainty and fear, students can be supported in embracing change. Furthermore, life-long learning acknowledges that even after adolescence, students will need to constantly step onto new bridges, as spaces of transition. Rather than any single destination, learning becomes an ongoing process of crossing new bridges.

life-long learning acknowledges that even after adolescence, students will need to constantly step onto new bridges, as spaces of transition. Rather than any single destination, learning becomes an ongoing process of crossing new bridges

Similarly, as teachers, we ourselves must cross and re-cross bridges. Life-long learning includes embracing the knowledge that our purposes, passions, interests, and joys can and will change. While there is an undeniable sense of safety in the notion of reaching one’s destination, bridges are hardly meant to be used merely once. Hence, teachers have a responsibility to be open to the breadth of experiences that they bring to their learners, for them to seek out new ways of thriving in the world.

Professionally, I have always been more comfortable with frontal and text-based teaching. Having benefitted from the lecture-tutorial system as a student, I viewed lectures as the principal opportunity to learn from a teacher’s mastery and synthesis of the subject material.

However, my first lesson in life-long learning as a teacher was to de-centre the self. Teachers must find ways to constantly bring lessons alive to different learners, rather than simply preach to the converted. It isn’t enough for Literature educators to bemoan the growing irrelevance of their subject, for instance, but our responsibility to make the magic of the written word accessible and engaging for all learners (Choo et al., 2020).

For instance, during QCR52B Aims and Approaches to Teaching Literature, our tutor Associate Professor Suzanne Choo showed us ways to make storytelling, narrative and literary analysis tangible through a range of picture books, storytelling games and even dramatic soundscapes. Mr Ken Mizusawa, our tutor for QCR52A Literature Reflection and Practice, is an unwavering advocate for drama-based pedagogy. I was fearful of these practices because they differed so much from my own experiences of literary joy, which involved gathering in small, close-knit groups to pore over each line of text with my friends.

Yet, by stepping again onto the bridge and facing my fears, I was able to discover new ways of seeing Literature education. I was inspired by approaches which highlight Literature’s spatial competencies and the potential of learning journeys, both physical and virtual (Chew, 2020; Whitehead & Tang, 2013).

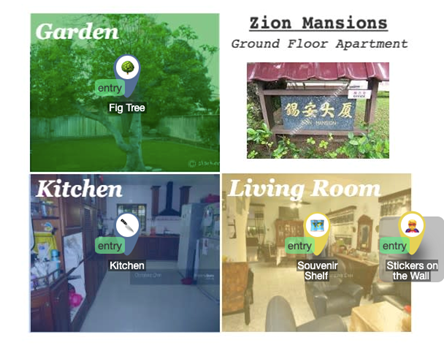

Hence, I used Deck.toys to create an immersive house tour experience for Jean Tay’s Boom (https://tinyurl.com/zmansiontour). Students click on the objects and explore their symbolism. These objects are illustrated with curated photographs and tagged with relevant quotes from the text. Hence, students can visualise a better understanding of the play’s richly symbolic objects, including their textures, material properties, size, and shape, which contribute to their understanding of the play’s setting and atmosphere.

Boom home tour on Deck.Toys

Returning to that first departure from Singapore: soon after crossing the jet bridge and stepping onto the humming aircraft, I was rewarded with breath-taking views of the earth, sky, and stars, as we crossed into new territories. By being open to stepping onto bridges, we are often rewarded with magnificent views.

Life-deep Learning | Content Mastery

Prebends bridge

Prebends bridge (1778), with its “spectacular” views of both Durham Castle and Cathedral, is a fond favourite of artists and photographers (ICE, n.d.). While admiring the view atop its three majestic stone arches, I always wondered how bridge construction takes place within a moving water body.

One construction technique involves building a cofferdam: a temporary structure that blocks out water (McFetrich, 2019). Cofferdams were often built by driving wooden posts or piles into the riverbed. The water within this structure (think of a wall) is then pumped out, which facilitates construction of the bridge’s piers (think of pillars). (Scan the QR code to see an animation)

I have come to view NIE as the construction of a cofferdam for the teacher’s bridge, offering student teachers the space to explore and build firm foundations. These foundations represent the call to life-deep learning as we deepen our understanding and expertise in our professional practice. Teachers are called upon to reflect, inquire, adapt, and innovate. Only then will these stable pillars hold fast, even as the waters return, and we plunge into the ebb and flow of teaching.

Teachers need to engage in processes of inquiry and reflection, where we adapt by understanding what works for students and what doesn’t. For those less familiar with Literature, interpreting a text first involves generating a range of responses to the words an author, poet or playwright uses. While reflecting on my own practice, one persistent challenge I faced was in expanding the range of successful text-to-world connections that students made.

During contract teaching, for instance, I found that my students had a strong grasp of language and made the right interpretive “moves”. However, they required further guidance in understanding how texts respond to contexts. My data included student responses on Google Documents and their essays.

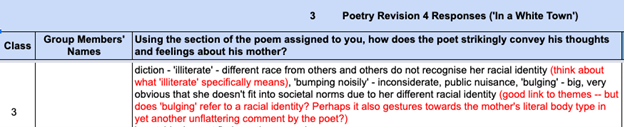

I taught British poet Daljit Nagra’s “In a White Town”, where the speaker’s Sikh immigrant mother is described as having an “illiterate body”. My secondary three students were able to rightly gesture to how this conveyed that the speaker’s mother was a “different race from others [who] do not recognise her racial identity”. Yet, how could I make the word “illiterate”, and the experience of linguistic alienation come alive to my students? How could I gesture towards the subtle allusion to the phrase “body language”, and how one’s physicality can loudly communicate one’s ethnic difference?

Student work during contract teaching

Hence, I have adapted my teaching processes to make full use of multimedia resources to build students’ schema – using the trailer for the Netflix documentary 13th (2016) to preface the teaching of Octavia Butler’s Kindred, for instance, and linking this pioneering work of science fiction in the African diaspora (“Afrofuturism”) with its contemporary progeny in Marvel’s Black Panther (2018). While this may seem common sense, it could be rather alien to Literature teachers who have been trained to exclude all extraneous material outside the text (what we call “Practical Criticism”).

Having a life-deep understanding of culture also requires us to understand that the teacher’s role is to make Literature accessible to all students: bridges must serve to connect. While my main area of content mastery remains interpretating the written word, Literature should be taught alongside the visual culture of its day and ours.

Indeed, students will join the cultural discourse from a point quite different from our own. Just as one cannot step into the same river twice, teachers must meet their students at the starting point of their own cultural context. Pop culture, fanfiction and memes can all serve as bridges from the world-to-text, complementing what has traditionally been considered “high-brow” and serious literary work.

For me in practical terms, I will always endeavour to source and collate relevant cultural and affective artefacts, including using The Greatest Showman (2017) to teach Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club (1989), or bringing out the experience of diaspora, third culture and border-crossing in both Crazy Rich Asians (2018) and “In a White Town”.

To return to Prebends, a plaque on the bridge displays the 19th century Scottish poet Sir Walter Scott’s words about Durham: its “venerable aisles / With records stored of deeds long since forgot”. Prebends remains beautiful to those viewing it today, despite the passage of time. I am sure it will remain beautiful for generations of students to come – who will find their own meanings within and relationships to the bridge as they step across its threshold.

Life-wise Learning | Discursive Bridges

Kingsgate Bridge, with Dunelm House in the left background

While Durham is a fine example of an English medieval city, one or two structures stand out against the Cathedral’s imposing stone finery. Strolling along Kingsgate bridge, one might think that its bare, concrete form is an oddity in a city of medieval beauty.

Built in 1963 (ICE, n.d.), it links the Cathedral on one end, to a building that it more closely resembles on the other: the Durham Student Union (DSU) building. Also called Dunelm house, it is a Brutalist concrete building with a dull, grey, and ageing exterior. In 2016, when I was a first-year student, a controversy erupted as to whether to de-list the DSU building as a heritage site and make space for a newer, more functional building. I was never too fond of Kingsgate bridge either, considering it bare in contrast to Durham’s finer stone bridges.

As a student, it would have been too easy to support the demolition of the DSU building as something practical. However, making a wise decision requires one to move out from one’s own perspectives. Wisdom is associated with justice and morality; indeed, life-wise learning includes the wisdom to move outwards from the individual to one’s society.

Upon some research for this article, I discovered that Kingsgate bridge was designed by the English architect Sir Ove Arup, whose work includes the Sydney Opera House. One of my favourite literary concepts is juxtaposition, where two things are placed close together for contrasting effect. As Guardian columnist Rowan Moore so eloquently argues, the elegant austerity of Kingsgate bridge is, in fact, a deliberate complement to the imposing heft of Durham Cathedral behind it. Together, the two structures exemplify “masonry’s full range of mass and levitation”, with “the stone cathedral tower piling up towards the sky” while “the concrete bridge rest[s] in the air” (2017). I wish that as a student, I had the wisdom to see how literary juxtaposition was equally compelling in real life – to better appreciate the deliberate and harmonious contrast between Kingsgate bridge and the medieval stone city surrounding it.

With this new knowledge, Dunelm House and Kingsgate Bridge have both come to represent a city in transition to me. They represent a heterogenous city in search of an enduring truth, that tries to bridge the old and the new(er). Similarly, to bridge discourse in a divided world, students will need to connect conflicting points of view.

Indeed, F. Scott Fitzgerald defined “first-rate intelligence” as “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function” (1945/2018). My personal philosophy and professional practice have always included community-building, and consensus-building is an important part of that life-wise work. Holding forums, discussion opportunities, and small-group learning – these are essential for teachers seeking to facilitate wise conversations on sensitive issues.

For instance, one lesson I planned as part of a group unit for QCR52B was titled “Ecological Justice in World Poetry”. Students analysed Nigeran poet Ogaga Ifowodo’s poem “XLV”, which addresses the pollution caused by Shell Nigeria’s oil extraction operations in the Niger Delta (Ahmed, 2021). My initial lesson design involved a debate between Shell (on the side of development) and Niger Delta inhabitants (on the side of conservation).

Reflecting upon this lesson now, I see the importance of engaging students in conversations about finding consensus. For instance, despite the seemingly diametric opposition between oil companies and environmentalists, oil companies can be held accountable in contributing to sustainability efforts, including the recent plans to transform Singapore’s sprawling Jurong Island oil facility. This was announced, rather aptly, at the ground-breaking ceremony of a Shell plant on Pulau Bukom designed to recycle plastic waste (Subhani, 2021).

Bringing this to the classroom, one key teaching action when consolidating a debate would be to ask both sides to review areas of agreement and identify further work to be done, as opposed to simply declaring a winner or loser. I aim to prepare my students to live wisely in society, equipping them with the dispositions to productively and collectively move the needle on issues close to their hearts.

Life-wide Learning | Crossing Boundaries, World Literatures

“Bridge of Sighs”, Oxford

My final bridge takes us southward from Durham to Oxford. Here, Hertford Bridge (often called the Bridge of Sighs) joins two parts of Hertford College. This distinctive skyway is the focus of many tourist photographs, and I loved looking out of its windows, with their marvellous view of the city’s heart.

We often speak of “zooming out”, adopting a “bird’s eye-view” and looking at the “big picture”. Indeed, bridges such as Hertford’s offer us new vantage points with which to survey the world, relook familiar landmarks and to connect the dots on the map. Similarly, NIE’s life-wide learning focuses on bridging connections between disciplines and across contexts.

In NIE, student-teachers capitalise on the real world’s learning opportunities, whether in the heritage trails that we designed for QED52E Singapore Kaleidoscope; the real-world problems we tackled in QED52P Group Endeavours in Service Learning, or the Student Development Experiences within and outside the classroom in QED52U Character and Citizenship Education in the Singapore Context.

Furthermore, I find that life-wide learning’s ambit includes the areas of our lives we consider less “academic”. If Literature purports to discuss the stuff of life, then we need to bring the world into the classroom. NIE’s life-wide learning focuses on adaptability and transferability across contexts, and I believe the most adaptable and transferable skills and knowledge emerge out of authenticity and self-awareness.

Part of life-wide learning in Literature is enabling students to bring their lived experience into the classroom. One of my most memorable and organic teaching experiences was inviting a student to connect her life experience to the GCE ‘O’ Level short story anthology, Hook and Eye. She was able to bring her own experiences of change, memory, and relocation in moving house to a rich reading of Yu-Mei Balasingamchow’s short story, “What They’re Doing Here”, where two food stall owners cope with the changes that life brings.

Teaching Literature as a bridge focuses less on received, “correct readings” than on forming points of contact between the text and the unique contours of our multi-faceted identities.

In addition, life-wide learning requires the breadth offered by global perspectives. One of my passions is decolonial and World Literature, where I am committed to teaching students Literature from the Global South. Doing so sheds light on our unique, hybrid position, as readers of Literature in English in an English-speaking former British colony.

But why am I so interested in such literature? By acknowledging that my reading and teaching practice is influenced by my life and academic history, I demonstrate one version of what it means to be a life-wide teacher.

I turn to Parker Palmer’s famous dictum in The Courage to Teach (1998), almost a truism for teachers today: that we teach who we are. Palmer encourages teachers to “scout out [their] inner terrain”, so as to “guide students on an inner journey toward more truthful ways of seeing and being.” Teachers need to become life-wide practitioners by building an intimately self-aware understanding of how their perspectives are shaped by their life experiences.

Palmer’s anecdote about Eric and Alan, two academics born into rural families of skilled craftspeople, is instructive. Thrust from the concrete realm of handiwork into the abstract ivory tower, Eric felt deep shame and insecurity about his background, feeling like a misfit in the elite realm of academia. This sense of inadequacy constantly bled into his professional life. In contrast, Alan found ways to honour “every major thread of one’s life experience” by literally crafting lessons with care and tying his academic vocation to his working-class background. Alan embraced what Eric instead hid as his inadequacies.

As a Literature teacher, I experience(d) persistent anxieties about being a competent cultural guide for my students. Studying Literature often implicitly requires some cultural capital (Loh & Sun, 2020). As someone who spent most of his life in a three-room Housing Board flat in Bedok South and was educated in government schools, I ask(ed) myself:

Have I read enough, particularly when I try to bring World Literature into the classroom? Is my own reading sufficiently sophisticated for my students? Do I have the je ne sais quoi, that “it” factor?

To do their work as bridges, teachers should lean into the stones they are built of: their rich, life-wide experiences. Instead of perpetually wishing away the inadequacies of my own knowledge, I learn to account for these fears – why am I fixated on arriving at “acceptable” readings?

The NIE digital portfolio is one tool that enables such metacognitive awareness. The digital portfolio initiative invites student teachers to understand and take stock of our development through rich retellings of our life and NIE journeys. We weave the fabric of our own life stories, bringing our experiences across contexts and into the classroom.

In reflecting on my formative university years and my changing views on education through the digital portfolio, I’ve come to strengthen my views of how we fail to acknowledge how odd the concept of Literature in English can be to a Singaporean student. As someone overawed by the venerable towers of Durham and Oxford, who seems like an outsider in Literature classrooms in the UK, I understand what it means to love something and yet feel like a stranger to it. Indeed, this sense of alienation has become my strongest critical and pedagogical tool.

Previously, English Literature was conceived as an ideological project in colonial Singapore, to fashion people’s taste, morals, and intellect (Choo, 2013). This, I contend, is the source of colonial mentalities which focus on which big-name authors to read (“You haven’t done Literature if you don’t read Shakespeare”), or to assess work based on what “Cambridge” would accept, as we often hear in class and staffrooms.

Instead, my experience tells me that I can productively leverage the tools of World Literature. As a field, it focuses on the circulation of texts outside their location of origin, taking as its starting point movement, openness and even alienation. It acknowledges that for a multilingual, multiracial former colony, it is okay to feel strangeness in reading John Keats’ “To Autumn” ode, while also appreciating and feeling something for those “Season[s] of mists and mellow fruitfulness”.

This acknowledgement of the intrinsic oddness of reading Literature in English in Singapore offers a unique analytical frame, a kind of looking from above while standing upon the bridge. Simply asking my students why they think we should read a set of texts from the Anglophone world reframes the colonial mentality of arriving at the correct answer, to seeking a multiplicity of answers when we acknowledge that our literary analysis is always contingent on time, place, and culture.

Beyond this, Literature will always have an affective, highly personal dimension that can be difficult to articulate. For me, love, in fact, was my own bridge into Literature: I fell in love with Literature just as I was falling in love with my now-fiancée. If students can discover what they love about life and find it mirrored in the literature they read, life-wide learning can truly become a reality.

Conclusion

As a Literature teacher today, I see my role as a bridge, leading students into the world and using that knowledge to dialogue with the text. Where naysayers may decry Literature’s lack of a single, definitive answer, it is that process of stepping onto, crossing and re-crossing the bridge of interpretation that matters to me as a teacher.

Finally, I believe that Literature is a bridge for social mobility, in that it provides one with cultural capital. Today, Literature in English builds bridges for people to examine not only themselves, but to cultivate the cosmopolitan dispositions to stand on the bridges that criss-cross an ironically smaller, more densely interconnected world. Just as Literature has brought me from Bedok South to Durham’s “venerable aisles” and Oxford’s dreaming spires, so too I hope that Literature can be the bridge for students to find their place in the world.

Credit to Gabriel Lim for the nostalgic, watermarked photographs of Durham, a long-time friend and PGDE (Secondary) colleague. His work can be found at @kwaypngshots on Instagram.

Today, Literature in English builds bridges for people to examine not only themselves, but to cultivate the cosmopolitan dispositions to stand on the bridges that criss-cross an ironically smaller, more densely interconnected world.

References

Ahmed, K. (2021, January 29). ‘Finally some justice’: court rules Shell Nigeria must pay for oil damage. The Guardian.

Chew, A. (2020). Walking the City: Developing Critical Spatial Competences Through Literary Texts in Singapore. In D. Yeo, A. Ang & S. S. Choo. (Eds.) The World, the Text and the Classroom: Teaching Literature in Singapore Secondary Schools (pp. 261-276). Pearson.

Choo, S. S., Yeo, D., Chua, B. L., Palaniappan, M., Beevi, I., & Nah, D. (2020). National Survey of Literature Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices. Singapore: National Institute of Education.

Choo, S.S. (2013). Mapping the Moral, Political and Aestehtic Objectives of English Literature Education in Singapore: The Period of Colonisation and After. In D. Yeo, A. Ang & S. S. Choo. (Eds.) The World, the Text and the Classroom: Teaching Literature in Singapore Secondary Schools (pp. 261-276). Pearson.

Fitzgerald, F. S. (2018). The Crack-Up. Alma Classics. (Original work published 1945).

Institution of Civil Engineers. (n.d.). Bridges of the River Wear. https://www.ice.org.uk/getattachment/about-ice/near-you/uk/north-east/publication/bridges-of-the-river-wear/ICE-Bridges-of-the-war-w5-0.pdf.aspx

Kwek, D., Hung, D., Koh, T. S., & Tan J. (2017). OER-CRPP Innovations for Pedagogical Change: 5 Lessons. Singapore: National Institute of Education.

Loh, C. E., & Sun, B. (2020). Cultural capital, habitus and reading futures: Middle-class adolescent students’ cultivation of reading dispositions in Singapore. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 41(2), 234-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1690426

McFetrich, D. (2019). An Encyclopaedia of British Bridges. Pen and Sword Transport.

Moore, R. (2017, February 12). Save Dunelm House from the wrecking ball. The Guardian. Palmer, P. (1998). The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. John Wiley & Sons.

Subhani, O. (2021, November 23). Singapore to transform Jurong Island into a sustainable energy and chemicals park. The Straits Times.

Whitehead, A. & Tang, C. O. (2013). “No Nostalgia in the Future of the Past”?: Exploring Local Texts and Spaces through Literature Field Trips. In C. E. Loh, D. Yeo & W. M. Liew (Eds.) Teaching Literature in Singapore Secondary Schools (pp. 42 - 54). Pearson.