The Student Who Held a Mirror to My Face

Microteaching for an English Language Curriculum Studies module

Microteaching for an English Language Curriculum Studies module

“Words are containers for power, you choose what kind of power they carry.” -Joyce Meyer.

The ability to achieve my aspiration of teaching today can be attributed to the simple words of belief and conviction that I could succeed from my teachers. These words, as simple as they were, had a profound impact on inspiring and motivating me to work towards my goals. Admiring the concern and care shown by teachers, I always knew since primary school that I wanted to be a teacher. But perhaps the defining moment that galvanised me towards this ambition was when my primary five teacher, unaware that I had this aspiration in mind, came up to me on a Thursday afternoon after English class and said to me, “Joshua, you should really become a teacher in the future. I believe that you’ll be able to do well.” It may have been a passing comment, but as a primary five student, those simple words gave me the hope, confidence, and encouragement I needed to work towards achieving this dream. This is especially since I was never enrolled in the “top” class, never attained stellar grades, or received outstanding awards.

This ambition was further solidified during my pre-university education. Not only had I performed less than satisfactorily for my O levels, but at that stage in my life, I distinctly remembered visualising my dream inching further away when I had to juggle the demands from school and caring for my ailing parents. Yet, despite these obstacles, throughout my entire three-year pre-university journey, my teachers would consistently (and with great fervour) emphasise, “Just because you are not in a Junior College does not mean you cannot succeed or do just as well!” These words of conviction not only expressed my teachers’ rooted belief that we, as a class, had the capacity to succeed but also inspired us with a sense of determination to expend effort and do well. In fact, these same teachers would go above and beyond their call of duty to constantly check-in and provide me with additional learning support to ensure that I kept pace with my peers. It may seem insignificant, but the words that we as teachers use carry immense power and influence. These teachers, who never once looked down on us or doubted our abilities demonstrated what it truly means to believe in the capabilities of every student, and that is what I aim to bring to my future classrooms and to my future students.

The Head and the Heart Knowledge

Keeping that in mind, I believe that teaching and learning can be conceptualised by a sharpener and pencil metaphor. Both items exist in an interdependent relationship that necessitates each other’s existence to be effective, useful, and productive. Without a sharpener, a pencil would eventually run out of lead and lose its effectiveness when it becomes blunt. In the same vein, a sharpener, whose sole purpose is to sharpen and ensure that pencils function successfully, would be rendered redundant and worthless without the existence of a pencil. Ergo, just as much as students look to teachers for guidance, support, and learning, we, as teachers, depend heavily on our students to grow in our capabilities and competencies by learning and reflecting on our experiences with them.

As sharpeners, our purpose is to uncover the full potential of our students to facilitate their flourishing as individuals not just cognitively but in the values and dispositions that they exhibit. For Aristotle so eloquently expressed, “educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.” Considering the complex and increasingly diverse society that we live in today, head knowledge is no longer sufficient for success. Rather, the HEART knowledge that encompasses values such as resilience, empathy, inclusivity and the like are the foundational dispositions that our “pencils” need to thrive in this volatile, ever-changing world. Cultivating both the head and heart knowledge, therefore, forms the basis of my teaching philosophy and is synergistically embedded at the forefront of my lessons and heavily leveraged when teachable moments present themselves. Thinking back, this pencil-sharpener relationship is what truly enabled me to identify, reflect, and learn from my blind spots and presumptions, notably from a unique student whom I encountered during my practicum experience.

A mirror to my preconceptions

My first encounter with this unique student occurred in the first week of practicum when I observed my English cooperating teacher (CT) teach the secondary three express class to whom I would be teaching both English and Social Studies to. Seated at the back of the class, I noticed how this small-built student with ruffled hair and overly big glasses would incessantly interrupt my CT during her lesson to field question after question. This would at certain junctures of the lesson even see him charging down the aisle while she was teaching to get her attention. On top of that, he was easily distracted and would at times even leave his seat to pace around the classroom, sometimes to the extent of walking out of the classroom to which my CT would have to then usher him back.

Having observed certain distinct behavioral traits, and from discussions with my CT, I found out that he was a Special Educational Needs (SEN) student diagnosed with autism and ADHD. Being a nervous practicum student-teacher whose main focus was aimed at doing well for my teaching practice, I recall anxiously going into “problem-solving” mode, scrutinising him as a problem and obstacle that I needed to manage and overcome to avert my potential downfall. At that point, the focus I prioritised was, “How can I get this student to sit down and not make noise so that I can focus on teaching the rest of the class?” It was not about supporting his learning. It was about managing his “problematic” behaviour. Thankfully, this mindset had a short lifespan and reached a turning point with one incident that occurred towards the end of my first week.

It was a Social Studies lesson and the students were tasked to form their own groups of five or six for a group work assignment. Standing at the back of the class, I utilised this opportunity to observe how students independently formed their groups. Amidst the sound of dragging chairs and tables, I noticed that the SEN student had turned around to a group of five students and was politely asking if he could join them for their group project. There was no malice or rudeness in his language or tone. All he said was, “May I please request to join and work with you?” (Yes, he did speak rather formally). To my surprise, with darting eyes and whispered murmurs that refused to acknowledge his presence, none of the five existing group members addressed him and blissfully continued with their own discussion. He politely asked a second time only to be greeted with the same silence and blithe disregard. With a loss for words, he then dragged his feet out of the classroom with slumped shoulders and started pacing along the walkway.

Following closely behind, I then went out with the intent of checking in on him and inviting him back to class but had not at all expected his next reaction. When he saw me approaching, he turned to me, with tears trickling down his face, and stuttered, “I…I tried to ask them politely if I could join them… but…but they just ignored me. Why did they have to ig..ignore me? Why can’t they let me join them… or answer me?” and he repeated, “I tried my best to ask them nicely… but they just ignored me…” Words cannot describe that deep sinking feeling that overcame my heart as I heard this student share those thoughts with his head bent low from disappointment. After comforting and assuring him that I would find him a group who would be excited to welcome him, I walked him back to class and noticed how there were a select few who were sitting alone at their desks, almost as if they were the “outcasted” few.

Heading back to my work desk with a heavy heart and thinking back about all that happened, I felt guilty and remorseful that as a teacher-to-be, I too possessed certain negative preconceptions about the SEN student and saw him as an “obstacle” to overcome, totally negating the fact that he was an individual who had feelings, and who wanted and deserved to take part in the learning process as well. I had often prided myself in the belief that like my own teachers who inspired and believed in me, I would model the same level of support, belief and encouragement to all my students, but it was almost as if this unique student had held a mirror to my face to reveal the unsurfaced assumptions that I may have tacitly held for certain groups of students. In my pursuit to do well and succeed, I had failed to recognise how he was an equal participant in the learning process. He may have had learning difficulties and challenges but he was someone who could feel, who could understand, and who could experience emotions just as well (sometimes more so than his peers). With that in mind, I was determined to find ways to facilitate and support his learning, and the question no longer was “How do I solve this problem?” but rather, “How can I best support his learning?” In addition, seeing that some students were left out of the grouping process, an additional guiding question was, “How can I foster greater inclusivity in the classroom?”

The Action Plan

Field notes taken from classroom observations

Field notes taken from classroom observations

To determine the best way to support the SEN student, I firstly relied on classroom notes taken from my observations of how both my CTs supported his learning. This involved the routines they would reinforce, the instructions they would give and the dispositions they would exhibit. I then augmented these classroom notes with conversations with each of them to better understand the thought process and rationale behind their routines, most of which were directed to the need to provide the student with a familiar and fixed structure to follow. Both CTs also exuded patience and calmness whenever they addressed him and never once raised their voice at him. I then turned to the literature, notably to the works of Levin and Nolan (2014) who promulgated the importance of establishing routines that are rationalised to support learners, especially those with special educational needs. Charles (2014) further postulates the criticality of routines to establish a safe environment for the student to learn.

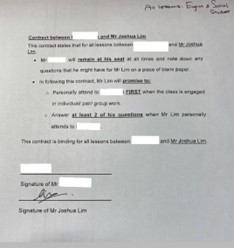

Personalised contract with the SEN student

Personalised contract with the SEN student

Integrating these findings, I then drafted up a personalised contract detailing the routines and expectations that I had for the student and myself during our English and Social Studies lessons. In essence, adopting some of the routines established by my CTs, my contract with this student involved passing him a piece of paper to sit and note down all the questions that he might have. In return, I would approach him during individual or group work to address at least two of his questions. We had a formal “signing session” where I rationalised why I needed him to abide by certain expectations like sitting down during lessons, and also sought to hear his opinions on the terms of the contract. After agreeing to the terms, we both signed on the dotted lines and therein started our learning contract.

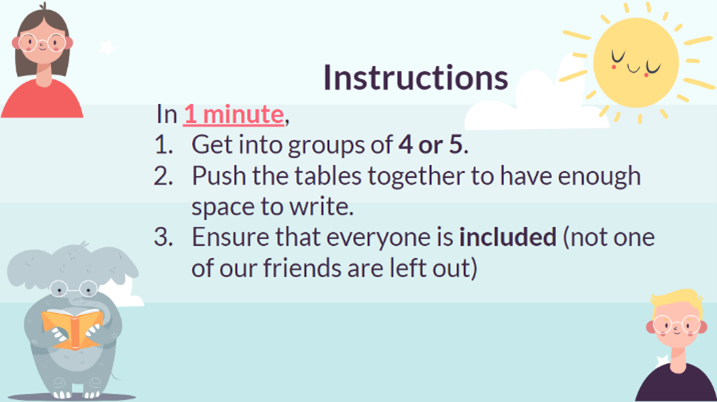

While supporting the SEN student, I also aimed to foster a greater sense of inclusivity among students of the class. To achieve this, I drew on my past reflection posts made on the digital portfolio with respect to one of my educational modules: “AED38A - Motivating pupils to learn”. In particular, according to the self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan (2000), the intrinsic motivation to act can be fostered when students are given a sense of autonomy and relatedness. Thus, rather than “forcing” students to be inclusive, I extracted my learning from these reflections to draft out my “group-work norms” which retained the autonomy and freedom for students to form groups of their choosing. However, the agreement would be that after a minute, I would not expect to see any student without a group. If the latter were to occur, I would regroup everyone based on a fixed-grouping system which I would have prepared. This essentially meant that classmates would have to keep a lookout to ensure that all their peers were included.

Group work norms

Group work norms

The Results

For the first two weeks, I would consistently (and patiently) remind the SEN student of the terms of the contract and would provide specific affirmation whenever he respected and upheld our agreement. On his part, he would also never fail to remind me to address his questions whenever the class broke into a group or individual work. Suffice to say, he responded well to the contract and still had many opportunities to contribute meaningfully to the class discussions. Subsequently, based on feedback from both CTs, they observed that he was definitely more on-task and respectful of the class norms. In addition, he remained largely seated for most lessons and the interruptions were kept at a minimum.

In terms of the class dynamics, after the implementation of the “group norms” and rationalising with the class why it was important to make sure everyone was included in the learning process, it was indeed heartening to hear student comments like, “Hey, do you have a group? Why not quickly pull your chair over to join us” echo throughout the class whenever group work was assigned. Towards the end of my practicum, this not only became a routinised norm, but the groupings were no longer “gender-specific” and mixed across the different genders and cliques.

My Ah-hah Moments

Embedded in most of my lessons are “ah-hah” moments that capture the key essential learning points that students have gleaned from the lesson. These, according to Vygotsky (1978), are acute in helping our learners articulate and retain their insights from the lesson. For myself, as a “sharpener”, I have indeed attained fresh “ah-hah” moments and perspectives on what it means to truly support and believe in every student. In our pursuit to be effective teachers, we may at times neglect students with special educational needs on the grounds that they just need to be managed in terms of their behaviour. This can get especially overwhelming when we have to support the needs of forty other students while also supporting such unique students. It may be easy, therefore, to forget that these SEN students share the same right to education as any other student. However, just as my teachers both in primary and pre-university displayed enduring conviction to support and believe in my capabilities, it would be remiss for me to do so for any other student no matter the challenge. My greatest joy throughout this entire 10-week practicum stint was in encountering, supporting, and getting to know the SEN student. It was a gratifying experience to witness first-hand how he was able to regulate his own actions while still actively participating and enjoying the lesson. His enjoyment and increase in his self-esteem are what provided me with the greatest affirmation as a teacher and I hope to adopt such unwavering beliefs for my future students.

References

Charles, C. M. (2014). Building classroom discipline (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037110003-066X.55.1.6

Levin, J., & Nolan, J. F. (2014). Principles of Classroom Management: A Professional Decision-making Model (7th ed.). Toronto: Pearson Education.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)