Learning How to Learn, Learning How to Live

“We teach who we are”.

This quote, originally by Parker Palmer, a renowned educator, was shared during one of our Character and Citizenship Education tutorials. I’m not one to exaggerate but these five words, strung together in this precise permutation, have shaken my beliefs regarding what it means to be an educator. It puts forth the suggestion that our personality, our very belief systems and attitudes towards life permeate every plan devised and every action executed. A scary thought is it not? That what we profess to be, is scrutinised at each moment during all our interactions with our stakeholders - students, colleagues, parents alike. Do I really want to teach the person that I am?

Well, daunting as these thoughts seem to be, I take refuge in my belief that I’m but another human being on a journey to know myself better and that I have the potential for more.

My name is Jeremiah Elijah Maria Francisco Lim and I teach the English Language and Social Studies at the secondary school level. Growing up, I found myself innately drawn to the mentoring aspect of teaching. I was blessed to encounter teachers who were kind, personable, compassionate and who lived up to their profession as educators. Beyond being knowledgeable in their respective subjects, I was drawn to their sincerity and passion. Most of all, their belief in the potential that I and my peers had despite our doubts. Essentially, cultivating this sense of faith in one’s capacity, instilling hope for the future and being exemplary in word and deed are key roles I believe teachers play in the education landscape.

Teaching Philosophy

My teaching philosophy is to “endeavour to facilitate learning with respect, empathy and professionalism so that students may learn how to learn and learn how to live”.

Embedded in this statement is my belief that learning is communal and thus, any effort to facilitate learning requires tremendous respect. School, being a microcosm of society, is an opportune time to develop prosocial dispositions and behaviour that foster a greater sense of community. Another belief within the philosophy is that learning is a growth process that takes time and effort. Without empathy, it may be a temptation to slide into a functional mindset that focuses on attaining grades rather than developing an authentic love for knowledge.

Process of Inquiry and Reflection

I set out on my practicum journey grounded in my teaching philosophy. This inevitably affected the areas of inquiry which I will share about in the subsequent parts of this chapter.

In Parts I, I will focus on the reflections I had with regard to creating a classroom culture conducive for meaningful discussions. In Part 2, I will share some practices pertaining to increasing student ownership.

Part I: Creating spaces conducive for discussion

Issue A: Managing the effects of routines

Having experienced the benefits of discussion-based learning through pedagogies such as exploratory talk and inquiry dialogue, I eagerly envisioned my classroom to take on a similar characteristic. However, after the first few lessons and some discussions with my cooperating teacher (CT), we postulated two challenges that inhibited the vision from coming to fruition. Namely, student engagement and effective questioning. In this section, I will describe the two challenges in turn and share some tools I employed to remedy the situation.

Getting students to articulate their opinions can only come about if they are first engaged in discussions. This was far from the case when I entered the classroom where only a handful of students were confident and ready to voice their responses when called upon. This invariably left little space for other voices to be heard and resulted in them disengaging from the discussion.

To address this issue, I enforced the “no-hands up” routine. This routine involved calling students to offer their responses instead of asking for volunteers. The original intent was straightforward: create opportunities for more students to engage in discussion. While the routine did increase participation to a certain extent, new issues were engendered and teething problems became more apparent.

For example, students who were less vocal tended to be softer and had difficulties in projecting their voice to the class. As such, there was a need for myself to repeat their responses. This need for their contribution to be repeated not only took up extra time but also broke the momentum of the discussion. As a result, other students who were trying to follow the discussion found it increasingly difficult to do so and ended up losing focus. Moreover, my conversations with my CT also revealed that some of the more vocal students felt constrained by the routine as they had less opportunities to engage in discussion. This also led to these students disengaging from the lesson.

In response to these issues, I was challenged to be more intentional in designing discussions and tweaking the routine. For example, I began to tier the questions during the pre-lesson planning in such a way that quieter students were assigned more closed ended questions while more vocal students were assigned open ended questions. Furthermore, I made adjustments to allow students to volunteer their responses if they really wanted to. Opening up these options as well as pegging questions to their readiness to verbalise their responses proved pivotal in encouraging a greater spirit of openness among students.

As the students became more comfortable in voicing their opinions, I seized upon the opportunity to introduce ICT tools such as a random name generator. One tool that has been particularly useful is “Classroomscreen” as seen in Figure 1. This online whiteboard has an array of affordances that aid students’ focus in class. For example, it has a name randomiser that effectively achieves the same intent as the “no hands-up” routine. In fact, this system is able to retain a list of students who have already been called during the lesson and ensures that no student is called twice! Furthermore, the text function also provides visual aid in representing the key questions for discussion. Other practical affordances include a countdown timer, quick poll taker and instant QR code maker.

Figure 1: Classroomscreen.com screenshot

Issue B: Learning through feedback loops

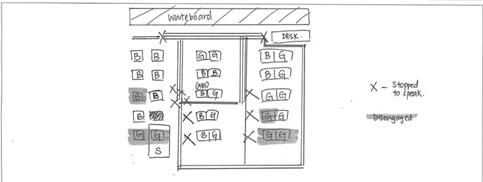

Besides the consequences of the routines I planned for, my CT was also able to point out that some actions taken in class subconsciously may have affected engagement levels. One of these seemingly insignificant actions was where I positioned myself in class and the number of times I spoke to students. To help me realise how this affected engagement, my CT monitored my movement using seating charts.

These charts became useful artefacts for suggesting possible reasons for ill-focussed behaviours observed in class. For example, in Figure 2, I postulated that my lower physical presence at the further end of the classroom might have resulted in more of the students positioned there disengaging with the lesson. After this was highlighted during a post-lesson conference, I decided to walk around the back of the classroom and intentionally engage those seated there through one-to-one conversations. As evident in Figure 3, while unfocussed behaviour remained, some improvement was achieved in terms of preventing them. This is an experience which proved the importance of having feedback channels (in this case, my CT) in highlighting unknown unknowns or matters which we may be ignorant about. Only in coming to awareness of my actions could I react accordingly.

Figure 2: Classroom movement chart (Class X) - 19 Jan

Figure 3: Classroom movement chart (Class X) - 26 Jan

To wrap up this portion of engagement, I realise that there is a need to constantly review the routines we introduce to the class and adjust them accordingly. Moreover, feedback from another pair of eyes is critical in expanding our view of what is occurring in the classroom. Without these seating charts, I am sure that I would not have considered the impact of my movement on engagement levels.

Issue C: Asking the right questions

Another critical component of facilitating meaningful and enriching discussions is planning questions effectively. In the previous section, I have highlighted more of the environmental factors that sustain learner engagement. For this section, I would like to share about the importance of sequencing questions for deepening learning.

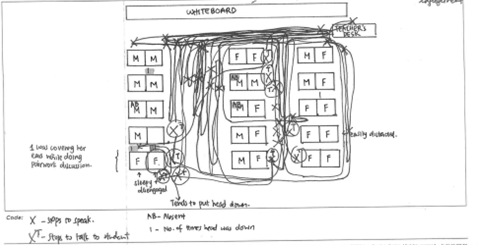

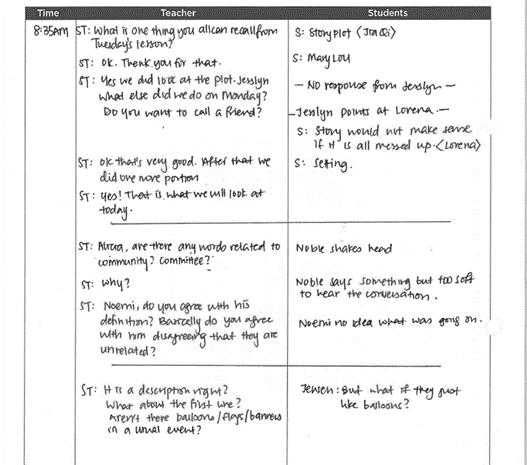

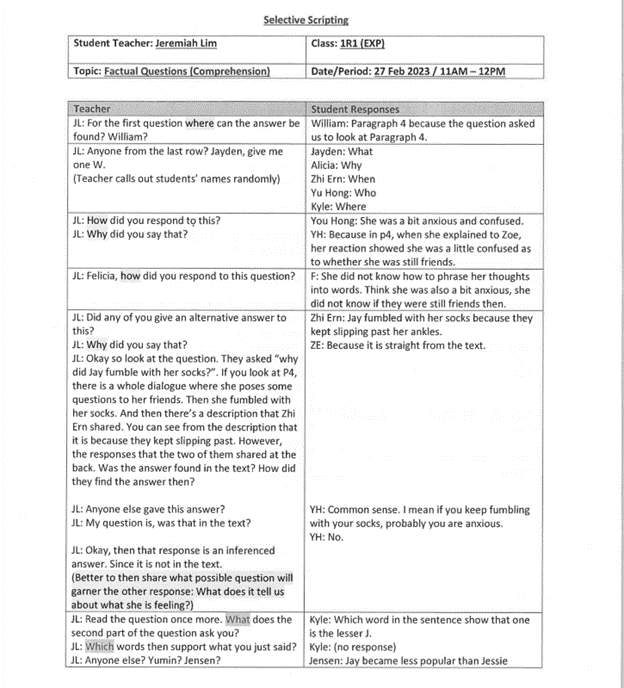

One of the observations pointed out during a post-lesson conference was the lack of momentum in the discussions I attempted to start in class. My CT used the “Selective Scripting” tool to highlight some instances when questioning could have been improved. For example, in Figure 4, it is apparent in the questions asked that I had a tendency to use rhetorical questions which limited students to a yes or no response. These leading questions effectively cut-off participation as students are not given an opportunity to practise higher-order thinking skills such as to substantiate their conclusion.

Another observation in Figure 4 is the reliance on mostly closed-ended prompts such as “What?”, “Do you agree?”, “It is a description, right”. Again, while these prompts may be useful at certain junctures of the lesson, they do not effectively probe the students to share their thinking process. Furthermore, there are questions that are worded in a convoluted manner which poses a great barrier for students to give a meaningful response. For example, “Do you agree with him disagreeing that they are unrelated?”.

Figure 4: Selective scripting (rhetorical and leading questions) - 19 Jan

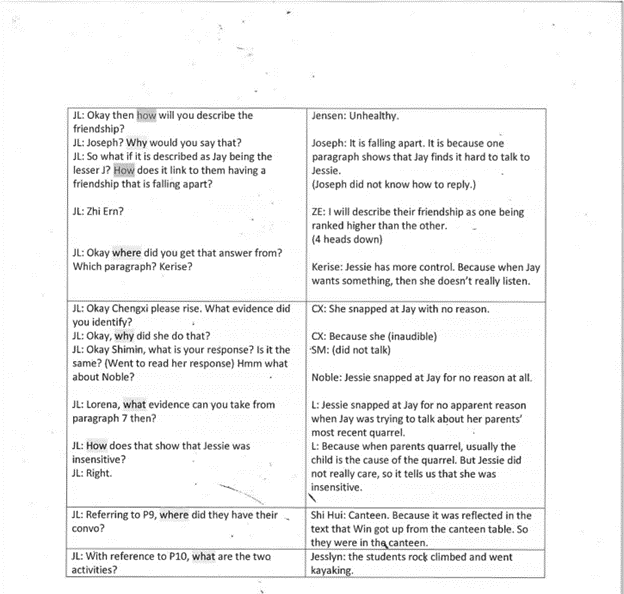

After reflecting on the nature of questions and the sequence in which they are asked, I became more aware of the impact these have on discussion-based learning. Essentially, if my questions lead students to a binary response, then there is a high likelihood that they are not actually giving their opinion but rather confirming the stance I seem to be suggesting. As a response to this observation, I sought to include more open-ended questions during discussions and anticipate the flow of conversation to plan for possible follow-up questions. For example, in Figure 5, question starters such as “Why?” and “How?” feature more regularly. These generate answers which show a deeper understanding of the text in question. Moreover, asking such questions allows for a greater variety of responses which thus allows more students to chime in with their own authentic thoughts. This is not to say, however, that closed questions have no place in discussions. As seen in Figure 5, questions such as “What?”, “Which?” and “Where?” become useful in clarifying students’ ideas or asking them to identify evidence.

Figure 5: Selective scripting - 26 Jan

To sum up this portion, I grew to appreciate the intricacy of planning questions according to instructional objectives. Through my inquiry of what works and what does not promote critical thinking among students, I learnt how to better choose questions that are appropriate to the juncture of the lesson. Whereas open-ended questions are geared at developing thinking, closed questions are needed for assessing specific ideas or probing for evidence.

Part II: Encouraging Student Ownership

Another important ingredient of creating a positive classroom culture from my observation is empowering students towards self-mastery and contributing to a communal learning experience.

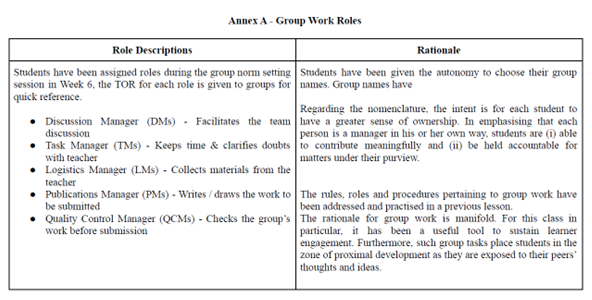

One of the ways in which I attempted to do this was in creating structures conducive for group work. Figure 6 shows the set roles I have assigned students to. As the naming deviates from the usual “leader”, “scribe”, etc. titles, I conducted a lesson with the sole intent of familiarising students to the terms of reference for each role and the routines for group work.

Figure 6: Group roles and rationale for naming convention

Suffice to say, students can engage effectively, efficiently and meaningfully in group work which enhances their participation in class and builds confidence.

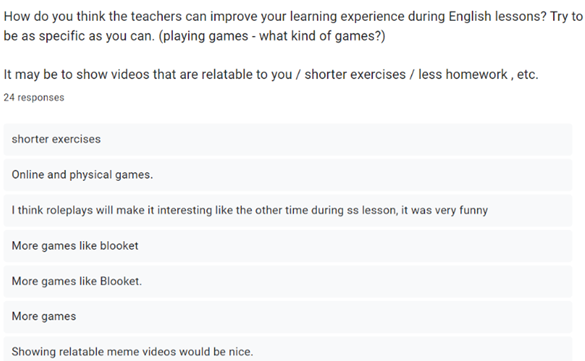

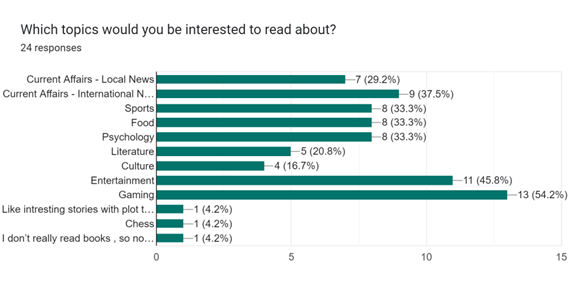

Another avenue to empower students is through active data collection via surveys. For example, conducting simple surveys through Google Form or infusing reflection questions into students’ worksheets gives students an opportunity to voice out relevant points regarding lessons. In Figure 7, students can be seen suggesting possible activities that will improve their learning experience. Similarly, Figure 8 shows data on students’ interest which guided me in choosing reading articles for them in the following term.

Figure 7: Survey on learning experience

Figure 8: Survey on student’s interest

The Reason for Inquiry

Learning how to learn and learning how to live are the two overarching goals I desire for my students. The first of these two goals focus on instilling dispositions that promote reflective practices which begin only when the student is able to take ownership of his or her learning. To this end, I have dabbled and will continue to create opportunities for empowering students in the classroom as I shared in Part 3 of the chapter. As for learning how to live, my approach is grounded in the reality that humans are social creatures and skills such as communication and collaboration are key in living a purposeful life. It is for this reason that I have conducted an inquiry into practices that facilitate inquiry through discussions as shared in Parts 1 and 2 of the chapter.

For myself, one of the necessary dispositions I have discovered in my professional journey is to be humble - humility to accept that our grasp of knowledge is finite and that there is always room to grow, because that which we seek, knowledge, is itself infinite.

The Road Ahead

I would like to end in the same way as I began this reflection with the quotation “We teach who we are”. Indeed, learning and teaching are deeply interwoven with ourselves: the values, virtues, weaknesses, strengths, etc. that make up who we are. For myself, one of the necessary dispositions I have discovered in my professional journey is to be humble - humility to accept that our grasp of knowledge is finite and that there is always room to grow, because that which we seek, knowledge, is itself infinite. While the journey ahead seems daunting and fraught with challenges, I am hopeful that there are infinitely many more things to uncover, not just on my own, but together with my students and fellow fraternity members.

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)