The Value of a Voice

A Teacher’s Voice

Me delivering the valediction at the Teachers' Investiture Ceremony

‘What do I have to say to a room full of strangers, of fellow aspiring teachers no less?’

This was a question I had to continually confront while preparing my valediction for the 2022 Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony. Given a voice in front of a crowd, what would I use it for? It was in this space of self-confrontation that I had to dig deep into my personal and professional beliefs, to interrogate my identity and what I stand for as a teacher and more fundamentally, as a person. After many profound, introspective and heartfelt conversations with friends and family, interspersed with undeniably difficult meditations on my own nebulous understanding of self, I started to gain greater clarity on what I would later speak about in front of a full auditorium, something I have always found inextricably intertwined with my core principles — the value of a voice.

Ever since I chose to become a Literature teacher, I have always been asked this question: “Why Literature?”, to which my reply till this day remains: “Because words are powerful”. Words have the power to shock, to excite, to anger, to inspire, to enliven new ideas and to offer solace in times of darkness. What is further electrifying about words to me is that, however objectively they are spoken, words are almost always emotionally charged. They colour meaning as they breathe life into our thoughts, they shape the way we experience the world and correspondingly the way we express ourselves, they are the very linchpin of human connection. The words we choose to use, whether in speech or in writing, are the product of a marriage between our rational and emotional sides, transcending the arguably false binary between thinking and feeling, and serving as a medium in negotiating and navigating the overlap.

Unfortunately, words are a crutch we often take for granted in making ourselves known to the world, even though they are the main means through which we are seen, heard and understood by those around us. While the right words when spoken by the right person at the right time can have a tremendous and lasting impact on another person, words ultimately ring hollow if they are said without intentionality, without conviction and, worse still, without regard for others. My first-hand encounters of being on both the giving and receiving ends of unsolicited, destructive words have galvanised my resolve to truly appreciate the transformative power of words, so as to use my voice meaningfully, purposefully and respectfully, both within and beyond the bounds of the classroom. This was the one thing I was sure enough about to use my voice for as a graduating student-teacher and something that remains a key tenet of my beliefs and values as a full-fledged school teacher now.

While I often found myself in opportune moments to use my voice during my time at NIE, be it to lead an overseas service-learning trip, to moderate conversations with ministers, to address the cohort as valedictorian, or to speak as a panellist at an international conference, I did not always have my own voice growing up. On one of the first few days of school in Primary Two, a new Social Studies teacher had come into class and caught me talking to a friend during the lesson. Furious, she reprimanded me in front of all my classmates and even threatened to put a picture of me outside the classroom labelled “Chatterbox”. To the impressionable eight-year-old me, her words were like a gag order stamped ineradicably on my mind. I remember the way I felt at that moment: fearful, embarrassed, and wronged. I began associating speaking up with dressing-downs. I stopped raising my hand to her questions even when I had the answers at hand. I learnt to keep quiet even when I had loud opinions to air. Over time, I felt as if I had lost my voice in the classroom. I forgot how to speak up.

It was then that I first realised how powerful a teacher’s voice can be, how deeply it can cut and how lasting the wound it inflicts. A tongue may have no bones, but it is certainly strong enough to break a heart. This was the episode that sparked my continual rumination on the colossal impact that a single voice can make, whether as a curse or a cure, and the ripple effect it has on a child in his or her formative years.

A student’s voice

As much as I believe in teachers using their voice to do right by their students, I think it is equally important to foreground student voices and stories. How then can we, as teachers, use our voice to support the voices of our students? How can we ignite their words and empower them to speak words that heal and lead to growth? I thought back about that same fateful incident and reflected on how I would have wanted to be heard and perceived as a student then, a student who disrupted the lesson but nevertheless a student who spoke to be listened to and not to be silenced. Ultimately, it dawned on me: it is by first and foremost recognising the human individual behind each pair of eyes staring back at us in the classroom that we can begin to extend love to our students, to hear their stories and to grow their voices. I remember an especially significant encounter with a Secondary One student during my second teaching practicum just this year, where I was facilitating a discussion with the class on the set text The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. Midway through the lesson, this student quite abruptly shot her hand up and flashed a quizzical look at me, before thinking out loud: ‘Cher, what do you think Hitler would think of our world today?’

That completely caught me off-guard and threw me off the rhythm I thought I had going for the lesson, much more so because of the fact that it was a formal lesson observation. I was genuinely surprised, but in a rather unexpectedly pleasant way. Transposing one of the most cold-blooded dictators of human history from 1920s Germany to 2020s Singapore? What would that be like? I found myself smiling back at her in spite of myself and could not help but want to explore this thought with her in greater depth, to take a peek into her inner landscape on which the conception of this notion found roots, sprouted and flowered. In that lesson, she taught me to see characters in the book in a new light, but more importantly, she showed me the acute child-like curiosity that our students inherently possess, translocating a character as if picking him up like a Lego figure and moving him onto a different nanoblock base plate. Beneath the playfulness of imagining such possibilities of time travel in a world without borders lies a keenly observant global citizen in tune with what is happening across both space and time, judiciously cognizant of the climate of uncertainty and evolution which characterises both worlds then and now. Beneath the childish instinct to remove the man Adolf Hitler from his socio-historical context and plonk him instead into postmodern 21st century is the beginning of a deep, visionary thinker capable of imagining and reimagining possibilities of collision between past, present and future – and even if it is but a figment of her imagination, she is experiencing the text beyond the words on the page, personally and politically at once.

By asking such difficult questions to which there are frankly no answers, she proved a thirteen-year-old’s astute awareness of the complicated, messy world we live in, which functions not in binaries of black and white but on a spectrum of varying shades and hues, and that controversy in issues of ethics and morality weigh heavily on young minds too as they do grown-ups’. This again reminds me of the importance of hearing our students' voices and not letting a teacher’s voice eclipse his or her students’. In the words of Parker J. Palmer in The Courage To Teach, ‘our students want to find their voices, speak their voices, have their voices heard. A good teacher is one who can listen to those voices even before they are spoken – so that someday they can speak with truth and confidence.’ A teacher’s job, to me, thus includes perfecting the art of listening, something that many can do but few can master. I believe the coalescence of teacher and student voices in the classroom does not come about without intentionality, but is definitely a goal within reach, especially by establishing a classroom climate that is caring and respectful and by opening spaces for students to speak honestly and teachers to listen patiently.

That particular incident truly impressed on me the meaning of education, which, for me, is about meeting students where they are and walking with them in this incredibly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world that we find ourselves in. Literature, in particular, allows me to open up conversations about the human condition and the labyrinth of human afflictions such as loss, discrimination and loneliness, all of which are essential discussions to have amidst the turbulence in their impressionable minds, overloaded with information but lacking in guidance on how to process them. To teach not what to think of the world but the plural ways to think about it is, to me, the hallmark of truly successful education.

Literature, in particular, allows me to open up conversations about the human condition and the labyrinth of human afflictions such as loss, discrimination and loneliness, all of which are essential discussions to have amidst the turbulence in their impressionable minds, overloaded with information but lacking in guidance on how to process them.

Me on the last day of Teaching Practicum 1

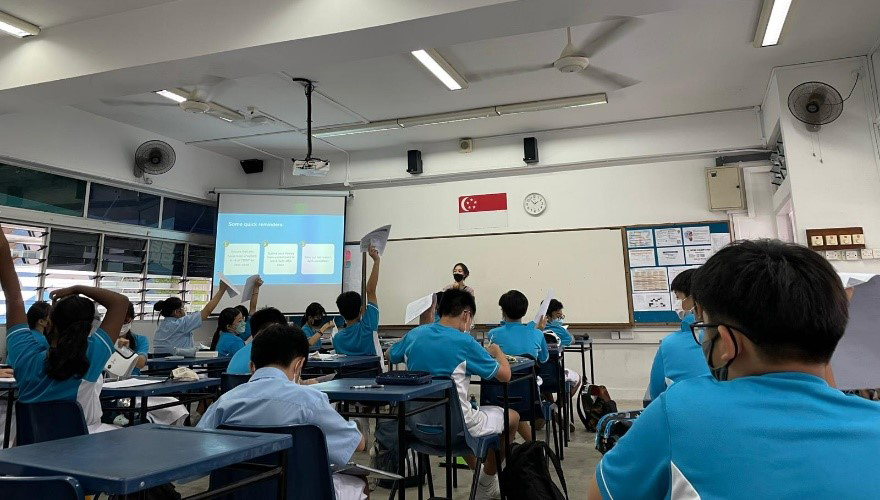

Secondary One Literature class

A student-teacher’s voice

With an abundance of information and a scarcity of attention, it is no secret that students no longer rely on teachers so much for knowledge acquisition as for affirmation, support, counselling and guidance for instance, as resilience and autonomy become an increasingly salient conversation topic in schools. Since the advent of the 21st Century Competencies, the entire teaching fraternity has been abuzz with talk of growing a future-ready generation of self-directed and multiliterate learners. But before our students can learn, grow and thrive in this VUCA world, it is pivotal to first have forward-looking teachers and schools – only with future-ready teachers to imbue a love for learning can we have future-ready students confident of navigating themselves in a post-truth world. Accordingly, schools are developing future-ready teachers by placing greater emphasis on the growth and learning of in-service teachers and student-teachers alike, to prepare us to respond to the challenges and opportunities of this new era, and in turn for us to prepare our students for the challenges and opportunities that await them decades down the road.

In these early years of teaching, I have learnt that an indispensable ingredient to becoming a future-ready teacher is to continually seek opportunities for growth – and by seek, I mean not only to embrace such opportunities when they arise, but to chase after them and hunger for them. To me, a growing teacher is someone who is unafraid of exploration and experimentation in his or her pursuit of excellence, whether in or out of the classroom, even if it means removing oneself from what is comfortable and familiar to try new ways to do things. This teacher is one who desires to stretch beyond his or her own recognition of self because of a conviction that boundaries (which are usually a product of conditioning) are meant to be challenged, if not broken, alongside a confidence that one’s potential has not yet been fully tapped. This teacher sees that growth in one’s professional identity is inseparable from growth in one’s personal identity – that is, to grow as a teacher is to also grow as an individual – because we bring to the classroom (and to the staffroom too, in fact) not just close-reading skills or pedagogical practices, but also our own personal histories and stories. These stories make us human, and perhaps even mediums through which our students can vicariously live and experience the world. This teacher understands that in order for his or her students to grow, for their horizons to be broadened and their perspectives enriched, he or she must first grow and develop holistically, because, after all, you can’t give what you don’t have.

This teacher sees that growth in one’s professional identity is inseparable from growth in one’s personal identity – that is, to grow as a teacher is to also grow as an individual – because we bring to the classroom (and to the staffroom too, in fact) not just close-reading skills or pedagogical practices, but also our own personal histories and stories.

Granted that growth should continue well beyond one’s early years of joining the fraternity and conceivably be sustained throughout one’s career, I found that the most conducive time for such growth and discovery for me was during my undergraduate years as a student-teacher. Besides providing the fundamental know-how in teacher training, my time at NIE also contributed significantly to my personal growth, and more importantly, made me realise the importance of working on myself before I can even begin to work on others, with others or for others. For one, my BUILD (Building University Interns for Leadership Development) experience with National Gallery Singapore fuelled my passion for the arts and fed my curiosity about the behind-the-scenes operations of the world's largest public display of modern Southeast Asian art as well as the local arts scene. In line with recognising teachers as humans with diverse interests and talents rather than mere transmitters of knowledge, this experience allowed me to venture into spaces, physical and intellectual, to try my hand at new endeavours and meet new people along the way. For instance, my experience co-organising the Asian Families Philanthropy Event at the Gallery gave me the unexpected opportunity to meet and hear from author, public speaker and venture philanthropist Ms Eileen Rockefeller and her husband Mr Paul Growald about sustainability and the climate crisis.

Apart from local opportunities, my growth in NIE extended internationally as significantly marked by the two overseas service learning trips I made to Sikkim, India, in 2018 and 2019. There, we engaged in various community involvement projects like assisting with sustainability efforts at Khangchendzonga Conservation Committee’s Zero Waste Centre, engaging in cultural exchange programs with local students at Padma Odzer Choeling School, and befriending orphaned children at Lepcha Cottage, run by Nobel Peace Prize nominee Ms Keepu Tsering Lepcha. Amongst the invaluable life lessons Ms Keepu impressed upon us through her speech and actions, I distinctly remember her espousal of the value of a voice. In order to truly know ourselves, we must, she urged, look within ourselves and hear our own individual voices amidst the noise surrounding us, because at the end of the day, one honest voice is louder than a crowd. These experiences indubitably helped me to grow my voice as a student-teacher and as a person, and remain some of the best memories I still hold close to my heart till now.

Riding this wave of growth, I was privileged enough to be recommended by Professor Low Ee Ling, Dean of Academic and Faculty Affairs at NIE, to present at the 2022 Forum for World Education held in Thailand. This international forum convened global business leaders, government officials, educational experts and aspiring young leaders from 17 countries to explore how the future of education can be shaped to match global economic trends, so as to improve workforce quality and education worldwide. With the opportunity to use my voice, this time on an international stage, I spoke on a panel about Education and Future Skills in a Shifting Landscape, traversing the topics of adapting education, inculcating future-ready competencies and fostering an entrepreneurial mindset in students against the backdrop of the recent pandemic, accelerated digitisation and new social, economic and political changes, so as to ride on great opportunities towards the future. Also at this forum, the Director for Education and Skills at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Mr Andreas Schleicher, shared immensely illuminating data and findings about the efficacy of education systems worldwide, making us in the audience think hard about difficult questions: What makes education systems successful? Why are some academically able students still inhibited from a growth mindset? How can we nurture our children to think like scientists and not science students? How can we find the balance between breadth and depth in teaching and learning, given our time-sensitive curriculums? How can we truly promote interdisciplinary thought beyond cross-disciplinary projects? How can we use technology to reimagine pedagogy?

In jostling with these questions in my mind throughout the forum, I realised that I had come full circle to my reflections on the importance of a single voice, whether it is a teacher’s voice, a student’s voice or a student-teacher’s voice, which was what first gave me impetus and inspiration to write this article. To use our voices rightly and not self-righteously in initiating dialogues, and opening authentic, honest conversations in order to find common ground and work towards a shared vision. As important as using our voice is listening to others’ voices, no matter how small or isolated they may be, because that is ultimately fundamental to our human need for recognition, love and belonging.

/enri-thumbnails/careeropportunities1f0caf1c-a12d-479c-be7c-3c04e085c617.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=d7261e3b_1)

/cradle-thumbnails/research-capabilities1516d0ba63aa44f0b4ee77a8c05263b2.tmb-mega-menu.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=1bc94f8_1)