Reflective practice and educational goals in the STEM classroom

Remember how they made you feel

Before I started teaching, I asked myself, “what kind of teacher did I want as a student?” I had a general idea of the kind of teacher I wanted to be and certain values I wanted to hold on to. However, it was not until I took the module on professional practice and inquiry, was I able to articulate my teaching philosophy that encapsulated what was important to me both as a teacher and a student.

As the saying goes, “students might not remember what you taught them, but they will remember how you made them feel.” When I reflect on my own experiences as a student and the kinds of teachers I had, I realise that I remembered some teachers more clearly than others. The teachers that were the most memorable were memorable, precisely because of how they made me feel. The teachers I was fond of were very kind, funny and relatable, while the ones I disliked were impatient, hot-tempered, and discouraging. I do not remember most of the lessons I had in school but I still have vivid memories of the moments that left me with strong positive or negative emotions, and by extension the teachers that made me feel the way I did.

Kindness and compassion distinguishes a knowledgeable teacher from an effective one.

Some of the most meaningful moments I had as a student came from the interactions and conversations I had with my teachers. A large part of why I still remember those moments was because of how I felt valued as an individual. Even as I recognised and respected my teachers as figures of authority, I also saw them as relatable and appreciated the genuine care they had for me. Kindness and compassion distinguishes a knowledgeable teacher from an effective one.

My teaching philosophy

After reflecting on my own experiences as a student, it was clear to me that I wanted my students to feel respected and valued just as I did. I think it is important to create a safe and positive learning environment where students feel recognised and have their autonomy respected. Whenever I take on a new class of students, I actively think about how I can better know my students and build positive relationships with them. In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, lower tiers of needs have to be realised before individuals pursue higher needs. This means recognising the social, economic and environmental factors that contribute to a student’s readiness to participate and learn.

After a challenging day of teaching, I will usually spend some time reflecting on my lessons. Reflecting on my practice helps me to evaluate if I have achieved the instructional objectives I had set before the lesson. Regular reflection also allows me to critically evaluate my planning, pedagogy and assessment practices, and consider if I‘ve done enough to create the conditions necessary for quality learning. When I strive to create a positive learning environment, I actively consider if my students have their emotional and psychological needs met. Meeting these needs is quite often a precursor for quality learning. Hence, when I encounter challenges like an inattentive student, or a student that struggles with classwork, I ask myself if I have created the necessary conditions for their learning. This could mean working with my students on meeting their emotional and psychological needs and modifying my teaching practices in the classroom to best meet those needs.

Taking a student-centric approach also means that my work goes beyond the classroom and that I have to work with other teachers, parents, counsellors, allied educators, and policymakers to advocate for my students. Much of the support that a student needs cannot be provided by a teacher alone, so there is a need to foster relationships with multiple stakeholders to advocate for our student. Students spend a significant amount of time in school, so as teachers we are in a unique position to listen to and understand the needs of our students, because if it’s not us, then who will?

Educational goals and the purpose of teaching

As a secondary school teacher, I work with students for about 1 to 4 years of their lives. The time they spend in school, though significant, takes up only a fraction of their lives. Hence, as a teacher, I am aware of the limited amount of time I have to work with these students. This means that when I plan for lessons, I have to prioritise learning experiences that develop the attitudes, skills and dispositions they need for the rest of their lives. I might be a Physics and Mathematics teacher, but I am not just training future scientists or mathematicians. I see my role as one where I provide students the tools and opportunities to achieve success and to live happy and fruitful lives. Valuing them as individuals also means championing their interests and passions, and allowing them to decide for themselves what success looks like. As Bill Waterson once said, “To invent your own life’s meaning is not easy, but it’s still allowed, and I think you’ll be happier for the trouble.”

I find that there is a general tendency to value learning as a means to an end,so as educators we need to clearly distinguish between education and credentials. We cannot let ourselves as educators be swayed by credentialism and then overemphasise assessment objectives. When I let good results become an educational goal, I risk teaching to the test. More often than I would like, I find myself emphasising content acquisition because I am focused on preparing students for a test or an exam. When I notice that about my instruction, I take a step back to think more deeply about why I am focusing on the things I do. If my only answer is “to prepare them for an exam”, I know that I am no longer clearly aligned to my purpose. This indicates to me that I need to realign my teaching to my goals as an educator.

Embracing flexibility and authentic learning

Authentic learning is an instructional approach where students engage in meaningful learning by working on real-world problems that are relevant to them. One of the ways I try to make my lessons authentic is through the use of dialogue, because it affords me opportunities to co-create knowledge with my students. By framing my lessons as dialectic, I not only ask my students questions but also encourage my students to ask me questions about what they are learning and why they are learning. This challenges me to think more deeply about how I can make learning meaningful to my students.

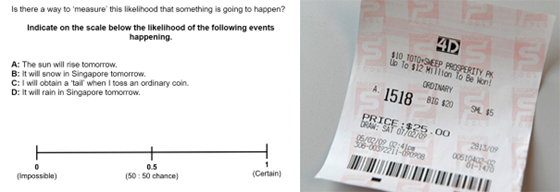

This dialectic approach also challenges me to be flexible about my teaching. Sometimes I plan lesson activities because I believe them to be meaningful. However, what I believe to be important might not always resonate with the students. For example, during a mathematics lesson, I introduced students to real-world applications of probability such as weather forecasting. In response to this, students ask me why it matters, because many of them do not actively look at weather forecasts, and having a prediction of the weather is not something they care much about.

At this juncture, I had three options:

- ignore that question and continue with the lesson,

- better connect the weather forecasting example with the students’ lived experiences,

- consider a different example that students might find more meaningful.

In response to this question by the students, I decided to try option 3 and offered students a different context. The context I chose was video games and loot boxes. I got students to think about video game loot boxes and what probability means in that context. I also extended that idea to gambling and the purchase of 4-D lottery tickets, where I tasked my students with calculating the chances of picking a winning ticket. Students were more engaged with this example and some students went on to ask: “Why not just purchase every single ticket and guarantee a prize?”, which prompted more classroom discussion where students considered the cost of purchasing every ticket against the prize winnings. Conducting this lesson in a way that encouraged authentic dialogue meant listening to what my students were saying and making a decision to deviate from what I had originally planned. Ultimately, I felt that it was a wise decision as this shift meant that my students were more engaged with the material, went beyond learning a mathematical formula and were actively exercising mathematical reasoning.

Lesson on probability

Finding meaning in the mundane

In an ideal world, students engage in learning because they are passionate about what is being taught, which in turn inspires joy in their learning. However, not every lesson objective maps onto authentic experiences. When the content that I teach is abstract or not easily relatable to students, I find it useful to think about the related knowledge, skills, or dispositions that can be developed through the teaching of such content. I then try to find interesting activities that I can use to spark curiosity and engagement, and as much as possible, focus on finding meaning even in the most mundane of topics.

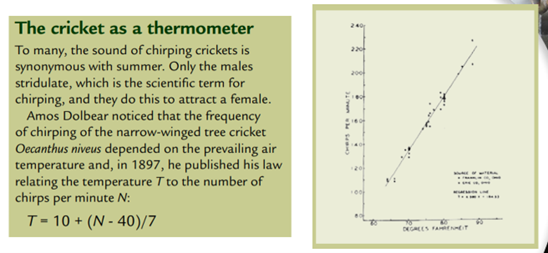

During a physics lesson on the topic of temperature, I had to teach students about thermometric substances and how to calibrate a thermometer. Most students will never have to calibrate a thermometer, so instead of just focusing on calibration in itself, I used this lesson as an opportunity to introduce the concept of limits and boundary conditions which is something that is found everywhere in the sciences. During the lesson on temperature, I shared with students an interesting discovery about how the frequency of cricket chirps can be used to measure surrounding temperatures, known as Dolbear’s Law. The law is an example of scientific or mathematical modelling which is very prevalent in the sciences.

Lesson on temperature and Dolbear’s Law

In the classroom, students encounter scientific knowledge as a series of discoveries or facts, but I make it a point to challenge my students to think about the contexts in which these facts hold true. For example, in the case of Dolbear’s Law, I would ask my students to think about the limitations of the linear model. Can one use crickets to measure any temperature? Most students would correctly identify that there are limits to the model and it cannot be used to predict temperatures that are too high or too low because crickets can only survive in a limited range of temperatures. All thermometers have similar limits, where they only have thermometric properties within a range of temperatures.

As with any form of knowledge, context matters. So being able to think about assumptions, limits and boundaries when encountering new information is a skill that students need to develop to be critical thinkers and to be able to evaluate the value of what they learn.

Embracing scepticism as a learning goal

As Carl Sagan said, “We make our world significant by the courage of our questions and the depth of our answers''. I think this quote encapsulates the chief learning goal I have for my students. My hope is that students embrace healthy scepticism, to not be afraid to ask questions, to seek answers and to continue to be life-long learners.

Much of humanity's progress can be attributed to our thirst for knowledge, and as a physics teacher, I have a particular affinity for how scientists seek to understand our world. In the natural sciences, one might look at the world and ask why natural phenomena occur the way they do. But an urge to question and a desire for answers does not only matter in the natural sciences. In the social sciences and humanities for example, one might ask why humans behave and interact with one another the way they do, or seek to understand how culture shapes and is shaped by our participation in it. Questioning also holds a lot of value in practices of creative expression. In the literary arts for example, a novelist or poet might ask how language can be used to capture the essence of the human condition. The value of questions transcends all disciplines and it is through the act of questioning that we find answers, some of which have profound implications for how we live our lives.

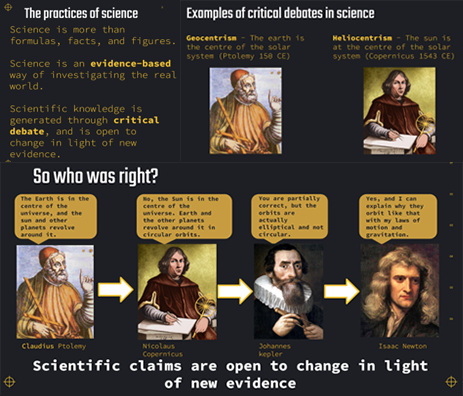

Questioning and critical debate in the science classroom

During Physics lessons, I would introduce historical examples of critical debates in the sciences to highlight how science is an evidence-based approach to investigating the real world. One such example is the historical debate between geocentrism and heliocentrism, where scientists were trying to answer the question “what does our solar system look like”? By using historical contexts, I can emphasise how science is not just a compilation of formulas, facts and figures, but is an approach to constructing knowledge that relies on questioning what we know and seeking answers for what we do not know.

Lesson on scientific argumentation and critical debates in science.

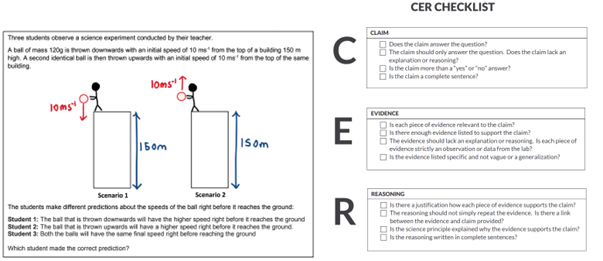

Being able to ask the right questions is a skill that requires an understanding of what one knows, doesn't know, and should know. Therefore, it is important that students have opportunities to reflect on their own knowledge and to practise and develop questioning skills.

I have worked with colleagues in designing lessons where we used a Claim, Evidence and Reasoning (CER) framework to get students acquainted with peer feedback and scientific debate. For example, we conducted lessons using the CER framework - students were tasked with solving a problem where they had to determine the speed of a falling ball. As part of the activity, students had to craft a solution by identifying the evidence and justifying their answers before presenting it to their peers. Students then evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of the different solutions before deciding on the most convincing argument presented. Through this activity, students get to emulate the process of questioning and scientific debate as practised by actual scientists.

CER lesson activity and checklist

To succeed, double your rate of failure

Thomas Watson said, “Would you like me to give you a formula for success? It’s quite simple, really. Double your rate of failure”. This quote best encapsulates my perspective towards failure. One of the most important responsibilities I have as an educator is to guide students towards accepting failure. When I speak to my students and ask them about how they feel about their performance in school, I almost always receive feedback about how afraid they are to fail. Being afraid of failure indicates a desire to achieve, and naturally, striving for something comes with the risk of not attaining it. Students that do experience failure risk developing negative self-efficacy that affects their sense of worth, so it is important that students see failure as normal, and more importantly, as beneficial for their growth.

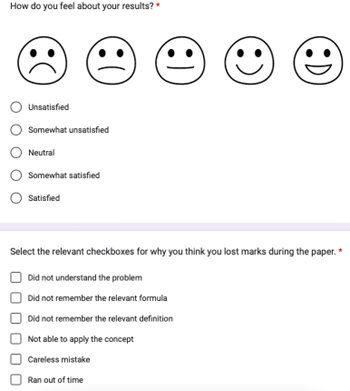

Being able to learn and grow from failure takes practice, so one of the ways in which I try to facilitate this process is through the use of reflection exercises to promote metacognition. After every summative assessment, I encourage my students to reflect on their preparation before the assessment and to think about the factors that contribute to their performance.

Beyond understanding the factors that lead to their performance, students also need to be equipped with tools that they can use to learn from their failure. I provide students with resources that target the effort and strategies they apply in preparing for assessments. Strategies like the use of concrete examples, elaboration, retrieval practice, spaced practice, dual coding, and interleavening have been shown to be useful for effective learning.

Post-exam reflection activity for students

Most importantly, as much as I support my students through the process of failing and learning from that failure, I also make it a point to emphasise that doing well or doing badly on an assessment is not in itself a measure of one’s worth.

Modelling failure as a teacher

How we treat ourselves and our peers as teachers should be coherent with how we expect our students to treat themselves. If I present failure as something that students can grow from, and I do not judge my students for failing, it is only fair that I expect the same of myself and my peers. It is said that teachers are role models to the students they teach, so it is essential that we model the attitudes and dispositions that we expect from our students, lest we hold them to standards we would not hold ourselves to. So as educators we need to embrace a culture of failure within our own fraternity. Just as we provide the space and support for students to learn and grow from failure, we too must do that for ourselves.

It is said that teachers are role models to the students they teach, so it is essential that we model the attitudes and dispositions that we expect from our students, lest we hold them to standards we would not hold ourselves to.

Over this past year of teaching, I have had a fair share of struggles especially when it comes to implementing effective lessons. I have tried many teaching approaches, lesson activities and assessment modes that did not work as well as I had hoped. However, being able to take those failures in stride has helped me become a more reflective and flexible teacher. As I continue to try and fail, I also find myself able to make quicker changes to lessons and respond to the needs of my students better than before. Over time, I have adopted, abandoned and refined many of my teaching and working practices and it truly has been a year of continuous learning.

Over the past year I have found it useful to remind myself to focus on long-term goals as It can be easy to get caught up with setbacks in the classroom and to unfairly judge myself as being an ineffective teacher. I like to remind myself that some of the most important goals in education, namely values, attitudes and beliefs, cannot be achieved through a single lesson or measured through a single assessment alone.