Self-Regulated learning

Assistant Dean, Teacher Leadership & Professional Inquiry, Office of Teacher Education, NIE, NTU

Assistant Professor, National Institute of Education - Psychology and Child & Human Development, NIE, NTU

Published: 1 May 2023

Overview

The Concept of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL)

he concept of self-regulated learning (SRL) emphasises the role of the self in establishing learning goals and strategies, and how the learner’s

perception of the self and task affects the quality of learning that transpires (Paris & Winograd, 1999). Paris and Paris (2001) describe SRL as “autonomy and control by the individual who monitors, directs, and regulates actions towards

goals of information acquisition, expanding expertise and self-improvement”. Zimmerman (1990) defines self-regulated students as “metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviourally active participants in their own learning”. Metacognitively,

self-regulated learners are individuals who plan, organise, self-instruct, self-monitor and self-evaluate at various stages during the learning process. Motivationally, self-regulated learners view themselves as autonomous, competent and confident

in their ability to perform. Behaviourally, self-regulated learners are capable of selecting, structuring and creating environments that optimise learning.

Models of Self-Regulated Learning

There exist many models

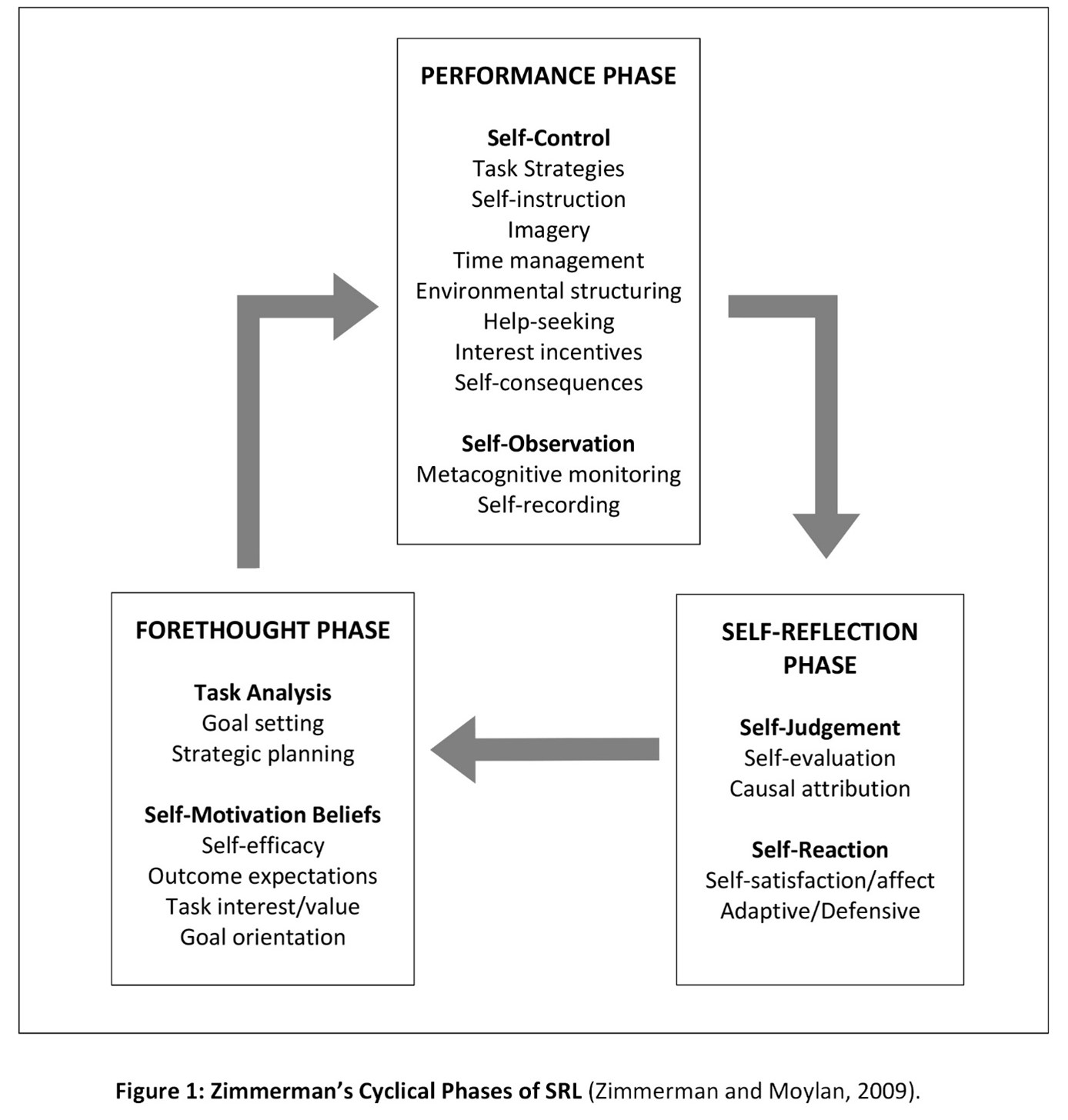

of SRL in the literature. Two of the most well-established and widely cited models in the field are those of Barry Zimmerman and Paul Pintrich (Panadero, 2017). Zimmerman envisioned SRL processes in three phases: forethought, performance and

self-reflection (see Figure 1).

(i) In the forethought phase, students analyse the task, engage in the setting of goals, and plan how to attain the goals. A number of motivational beliefs energises the process and influences

the use of learning strategies.

(ii) In the performance phase, students are involved in the actual execution of the task. They monitor their progress and use self-control strategies to maintain cognitive engagement and

motivation to task completion.

(iii) In the self-reflection phase, students assess their performance on the task and make attributions about their success or failures. These attributions generate self-reactions that

can positively or negatively influence how the students approach the task in subsequent performances. A good example of this phase is when a student engages in formative self-assessment and identifies areas for improvement.

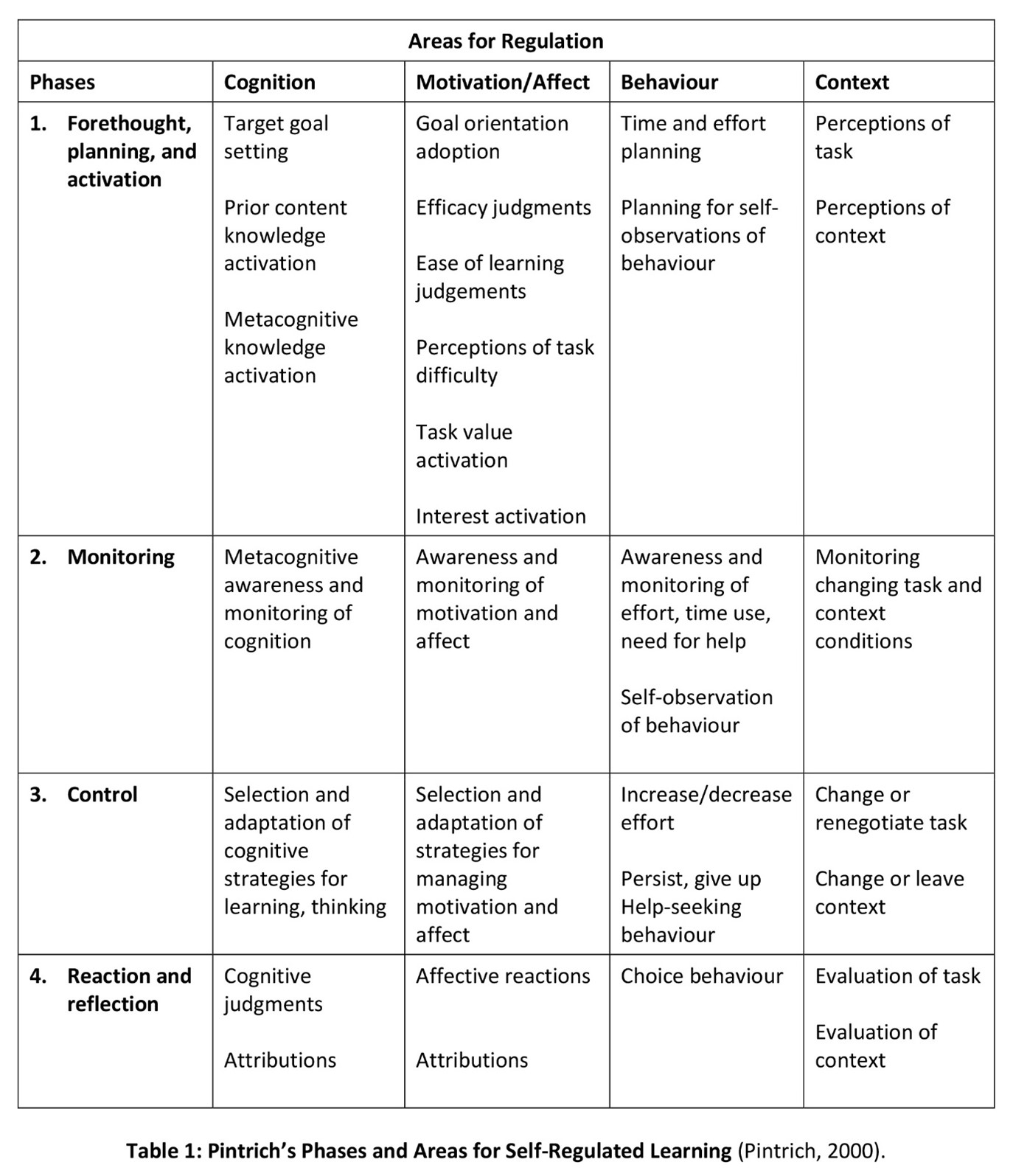

Pintrich proposed a social-cognitive model of SRL comprised of four phases: (1) Forethought, planning and activation; (2) Monitoring; (3) Control; and (4) Reaction and Reflection. Each of the phases comprises four different areas for regulation: cognition, motivation/affect, behaviour and context. A number of SRL processes are involved in the different combination of phases and areas (see Table 1).

The Singapore Context

In the Ministry of Education’s (MOE) 21st Century Competencies

Framework, one of the desired outcomes that MOE envisions for every student is to be self-directed. The aim is to nurture independent students with a sense of ownership of their learning so that they will thrive in the learning environment, persevere

in the learning journey, and be able to manage and plan their learning (MOE, 2018a). In 2018, MOE announced the “Learn For Life” movement, emphasising self-directed lifelong learning as an essential skill that students need to possess (MOE,

2018b). While coined differently, self-regulated learning parallels the notion of self-directed learning and the two terms have often been used interchangeably (Saks & Leijen, 2014). To empower students to learn for life and be future-ready, the building

of self-regulated learning capabilities becomes an important process and goal in Singapore classrooms (Chye, 2020).

In Practice: Development of SRL

Dimensions of SRL Development

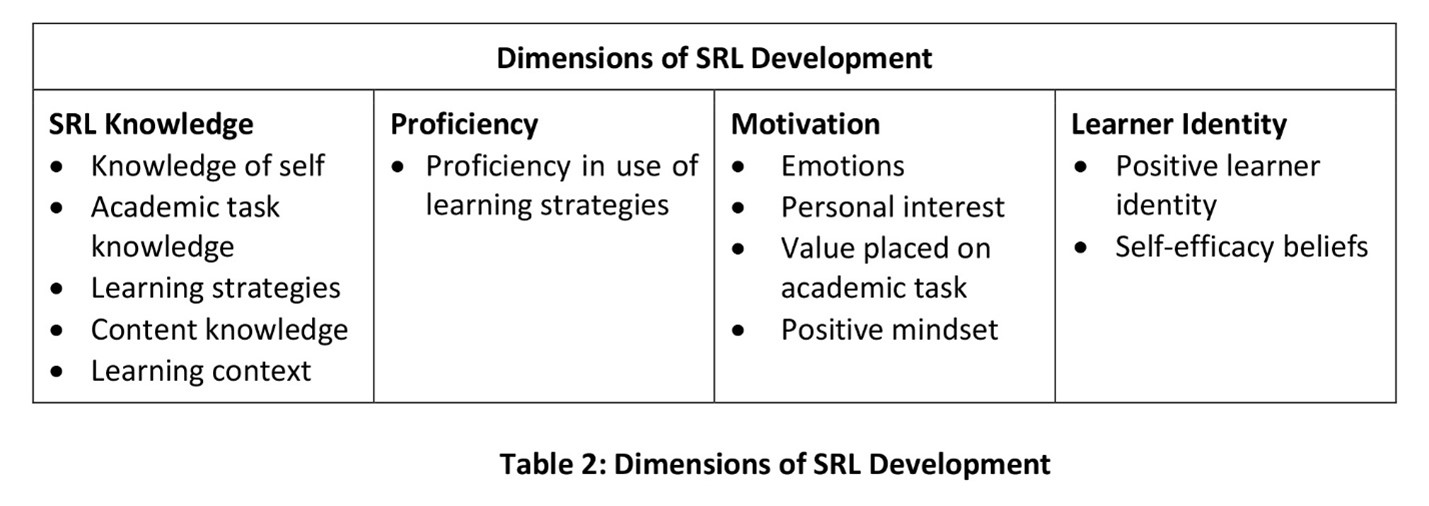

SRL instruction typically targets

the development of four major dimensions of SRL: (i) knowledge, (ii) proficiency in the use of learning strategies, (iii) motivation and (iv) learner identities (see Table 2).

The goal of instructional support for SRL is to

facilitate and integrate the various dimensions of SRL development, and this can be achieved through implicit or explicit supports for SRL development.

Teaching for SRL: Implicit Supports for SRL Development

The first direction

taken by educators is to provide implicit supports, whereby classroom environments and instruction are structured to enable opportunities for SRL development to take place (Paris, 2004; Randi, 2004). Teachers model SRL processes and create environments

that are conducive for SRL to occur. In the design of self-regulated learning environments, some guiding principles include clear learning goals and success criteria, allowing students to set learning goals, giving students choice in the learning process,

prioritising learning for the sake of learning, opportunities for self-reflection and self-monitoring, opportunities to test ideas and learn from mistakes, and iterative cycles of feedback and improvement. This can be supported by teaching practices such

as outlining learning goals and milestones, well-crafted driving questions, open-ended activities, reflection prompts, launcher activities, whiteboarding, reflective journaling, peer evaluation and formative assessments. Assessment for Learning (AfL)

strategies such as ongoing developmental feedback, self-assessment and peer-assessment can be used to create opportunities for students to evaluate and improve their own learning (English & Kitsantas, 2013; Leong, 2016). Strategies such as inquiry-based

learning and the use of digital portfolios can also be utilised to support SRL development (Chye, 2020).

Teaching of SRL: Explicit Instructional Support for SRL Development

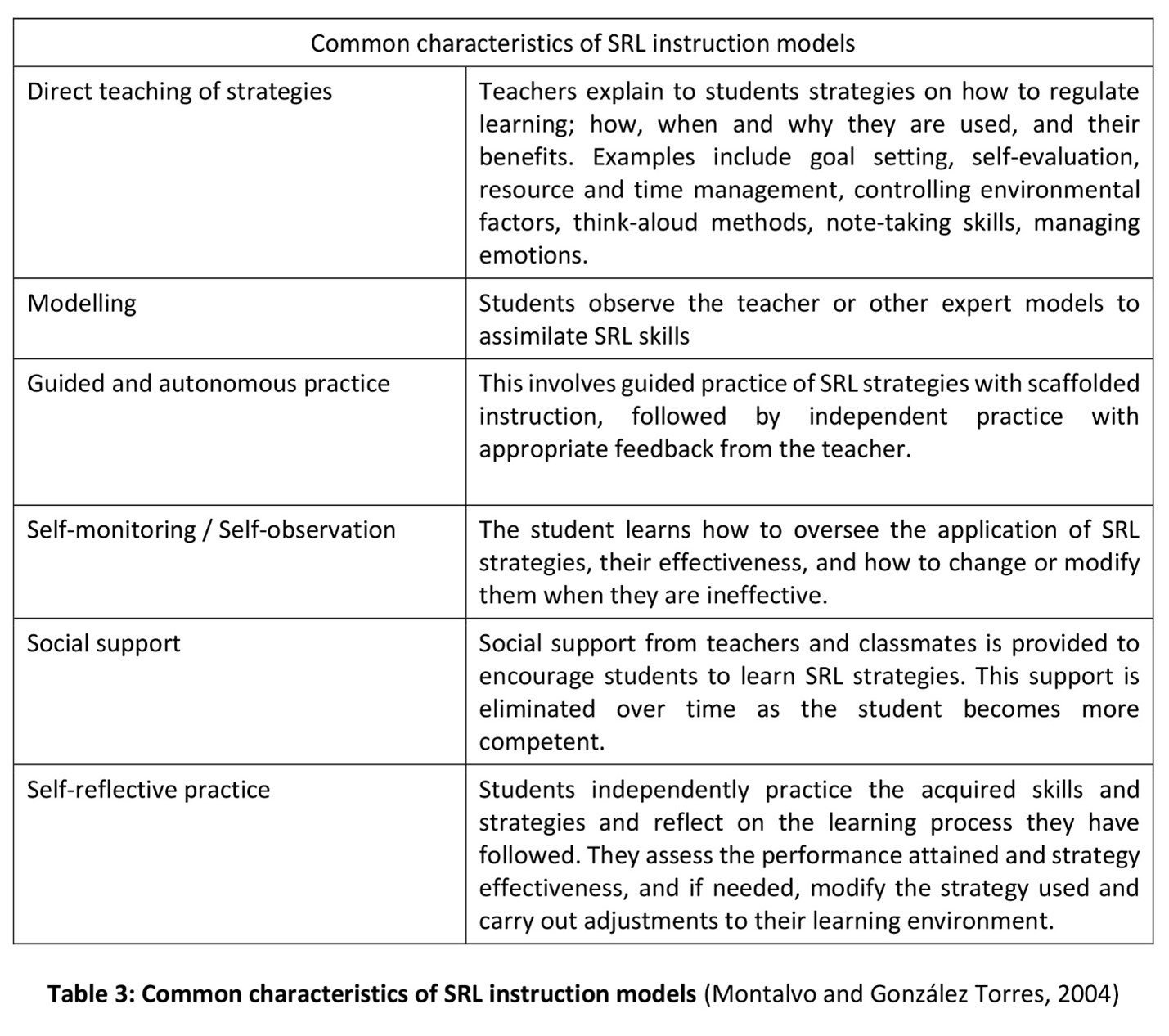

There are a number of principles and guidelines for

promoting SRL explicitly. Based on Zimmerman’s multi-level model, SRL skill development occurs in four stages: observation, emulation, self-control and self-regulation (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2005). Most models of SRL instruction feature

the following characteristics: the direct teaching of strategies, modelling, guided and autonomous practice, self-monitoring, social support and self-reflection (see Table 3) (Montalvo & González-Torres, 2004).

Takeaways

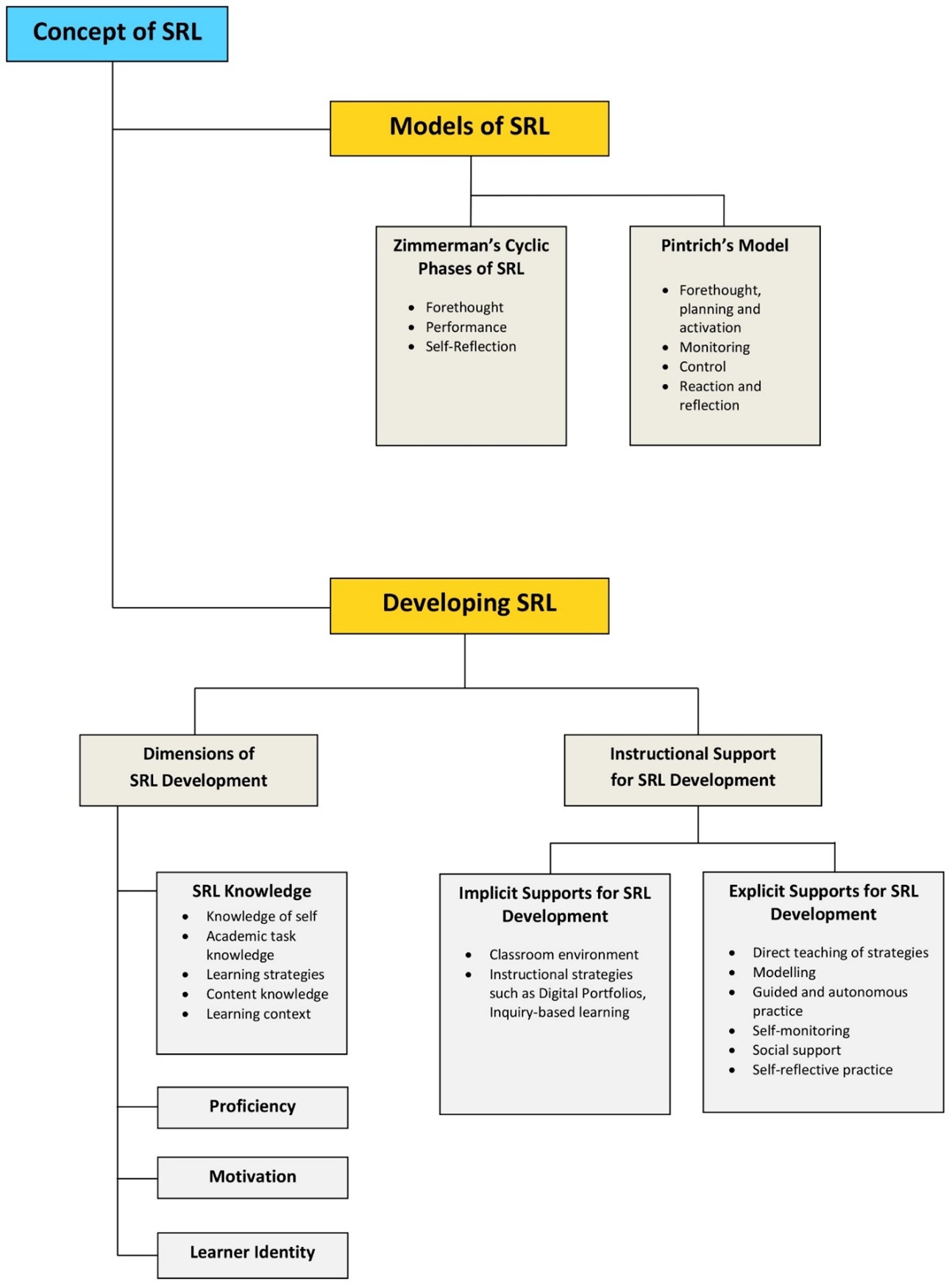

By developing SRL skills, students can build a foundation for lifelong learning, extend learning beyond the classroom and be ready for the 21st century workplace. The main points of the article are summarized in the concept map below:

References

Chye, S. (2020). Promoting Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research, and Practice. Singapore Teaching Practice, Singapore.

English, M. C., & Kitsantas, A. (2013). Supporting student self-regulated learning

in problem-and project-based learning. Interdisciplinary journal of problem-based learning, 7(2), 6.

Leong, W. S. (2016). Contextualising assessment for learning in Singaporean classrooms. Curriculum Leadership by Middle Leaders (pp. 100-115).

Routledge.

Montalvo, F. T., & González-Torres, M. C. (2004). Self-regulated learning: Current and future directions. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 3(1), 1-34.

MOE (2018a), Framework for

21st Century Competencies and Student Outcomes, Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2014/04/information-sheet-on-21st-century.php

MOE (2018b), Opening Address by Mr Ong Ye Kung, Minister for Education, at the Schools Work Plan

Seminar, Retrieved from https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/speeches/opening-address-by-mr-ong-ye-kung--minister-for-education--at-the-schools-work-plan-seminar

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: Six models and four directions

for research. Frontiers in psychology, 8, 422.

Paris, S. G. (2004). Principles of self-regulated learning for teachers. In J. Ee & A. Chang & O. S. Tan (Eds.), Thinking about thinking: What educators need to know (pp. 48-71).

Singapore: McGraw-Hill Education (Asia).

Paris, S. G., Byrnes, J. P., & Paris, A. H. (2001). Constructing theories, identities, and actions of self-regulated learners. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Self-regulated learning

and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (2nd ed., pp. 253-288). NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.

Paris, S. G., & Winograd, P. (1999). The role of self-regulated learning in contextual teaching: Principles

and practices for teacher preparation. Contextual teaching and learning: Preparing teachers to enhance student success in the workplace and beyond. (A commissioned paper for the U.S. department of education project - Information Series

No. 376). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education: Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teaching and Teacher Education.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In

M. Boekaerts & P. R. Pintrich & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 452-502). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Randi, J. (2004). Teachers as self-regulated learners. Teachers College Record, 106(9), 1825-1853.

Saks, K., & Leijen, Ä. (2014). Distinguishing self-directed and self-regulated learning and measuring them in the e-learning context. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 190-198.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated

learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational psychologist, 25(1), 3-17.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2005). The Hidden Dimension of Personal Competence: Self-Regulated Learning and Practice.

Zimmerman, B.

J., & Moylan, A. R. (2009). Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. In Handbook of metacognition in education (pp. 311-328). Routledge.